The 1,000-year Legacy of Ibn Sina, Dr. Roy Casagranda & Museum of the Future’s Lessons from the Past

by Media Desk

The medical scholars during the medieval Islamic era placed great emphasis on the value of dissection and the knowledge of anatomy for the diagnosis of affected organs, the relationships of the organs to one another and the application of adequate medical and surgical treatment...

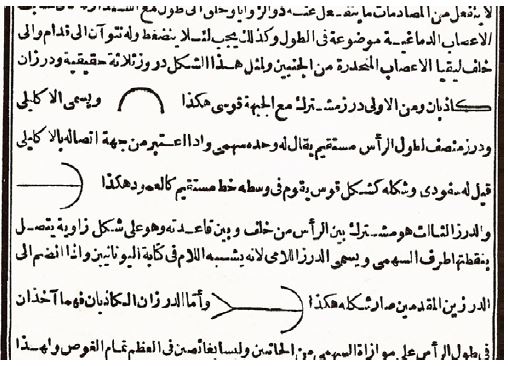

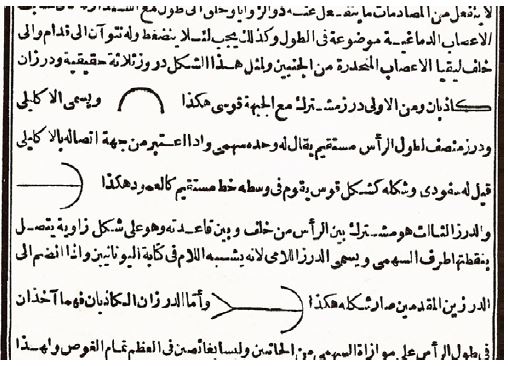

The presence of anatomical drawings within the medical textbooks was a trend that flourished in the Islamic era, reflecting an awareness of their educational role. During the whole of the Islamic era, with the increase in practical experience, the illustration of anatomical findings continued to progress in terms of quality and fine details. So, simple line-drawings illustrating the ventricles of the brain appeared in Kitāb al-Manṣūrī fī al-Ṭibb (Figure 1); also the cranial sutures in the Kāmil al-Ṣināʿah al-Ṭibbiyyah of ʿAlī ibn al-ʿAbbās al-Majūsī (Figure 2) and the al-Qānūn fī al-Ṭibb (The Canon of Medicine) of Ibn Sīnā (Figure 3); and the al-Mukhtar book of Muhadhdhab al-Din al-Baghdādī (Figure 4), who also made a diagram for the male urethra to illustrate its tortuous course (Figure 5). [1-5]

Figure 1: Part of a page from the first Maqalah in a manuscript of al-Mansūrī book of al-Rāzī showing diagrammatic drawings of the brain ventricles [54-55] |

Figure 2: Part of a page from a manuscript of ʿAlī ibn Al-ʿAbbās’ book Kāmil al- Ṣināʿah al-Ṭibbiyyah showing schematic anatomical drawings and descriptions of the cranial sutures [56] |

Figure 3: Part of a page from Kitāb al- Qānūn fī al-Ṭibb (The Canon of Medicine) of Ibn Sīnā showing his description and drawings of the cranial sutures [57] |

Figure 4: Part from a page from al-Mukhtar book of Muhadhdhab al-Dīn al-Baghdādī showing the cranial sutures [57] |

Figure 5: Part of a page from al-Mukhtar book of Muhadhdhab al-Dīn al-Baghdādī showing anatomical drawings illustrating the curvatures of the male urethra [58] |

Figure 6: Anatomical drawing of the maxillary sutures in one of the original manuscripts of Ibn al-Nafīs’ book Sharḥ Tashrīḥ al- Qānūn [59] |

Later on, more sophisticated anatomical illustrations were made, as in the diagram for the maxillary sutures in Ibn al-Nafīs’ Sharḥ Tashrīḥ al-Qānūn (Figure 6).

Figure 7: Anatomical drawing of the eye from the manuscript of Kitāb al-Kulliyyat (Colliget) of Ibn Rushd in Sacramento Monastery, Granada [60]

Moreover, the earliest known figures illustrating the anatomy of the eye appear in the Book of the Ten Treatises on the Eye of Abū Zayd Ḥunayn ibn Isḥāq (Johannitius, 809–873). Far more detailed, though less famous, diagrams for the anatomy of the eye are found in the Kitāb al-Kulliyyat (Colliget) of Ibn Rushd (Figure 7). It shows a transverse section of the layers of the eye as circles within each other, and in the centre is the lens. In front of the transverse dotted line, the layers from the outside inwards are: cornea, iris, and aqueous humour. Behind the dotted transverse line from the outside inwards are the following layers: the sclera, the choroid, the retina, and the vitreous humour. To each eye is attached an optic nerve which joins the other at the optic chiasma without crossing (in agreement with Galen), and then proceeds and join the brain. [7]

In the Kitāb al–Manāẓir of Ibn al-Haytham, he showed the layers of the eye represented by circles following each other to demonstrate how a straight line of light entering the eye through the centre of the cornea passes through the centre of the iris and comes in contact with the centre of the lens, then to the centre of the optic nerve, proving that the centres of all the layers are along one straight line (Figure 8). [8]

Figure 8: Anatomical drawing of the layers and humours of the eyes [61]

“Next is the diagram illustrating the brain, the two hollow nerves (optic nerves) and their cruciate crossing (optic chiasm), and illustrating the eye by showing its layers and humour. And I write on the humours their names and on each layer the letter ‘Ṭ’ [first letter of the Arabic word ṭabaqah meaning layer] to indicate it as a layer plus the first two letters of its name to identify it, wa-Billāh al-tawfīq.”

Figure 9: The drawing of the cross section of the brain and the eyes by the 13th century Khalifa ibn Abī al-Mahasin al-Halabī in his book Al-Kāfī fī al-Kuhl (The Book of Sufficient Knowledge in Ophthalmology) [62]

“This is followed by a full description of all the structures shown in the diagram with an apologetic note at the end, saying that “They were represented as far as can be done on the flat rather than the spherical plane.” [9-10]

So, in this time-honoured diagram that may well be based on drawings dating at least as far back as 1000 years, we get an insight into a modest attempt to represent what W.D. Sommering so luminously portrayed in his classic illustration ‘Table 1, in Horizontal Section Through Human and Animal Eyes’ in Göttingen in 1827. [11]

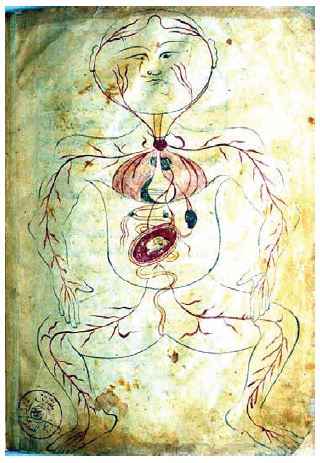

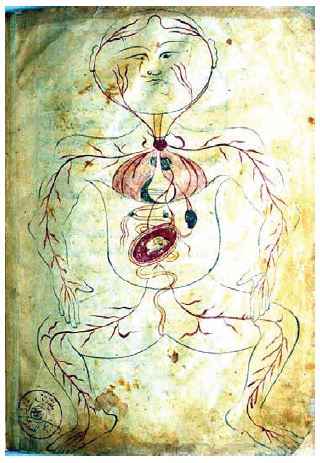

Another remarkable step in the evolution of anatomical illustrations during the medieval Islamic era was whole body diagrams made by the 14th-century Manṣūr ibn Muḥammad ibn Aḥmad ibn Yūsuf Ibn Ilyās (fl. around 1390) in his book Tashrīḥ-i badan-i insān (The Anatomy of the Human Body). The treatise, in Persian, consists of an introduction followed by five chapters on the five systems of the body: bones, nerves, muscles, veins, and arteries, each illustrated with a full-page whole-body anatomical diagram. The whole-body drawing shown in Figure 10 was used by Manṣūr to illustrate the veins of the body, but it also shows the viscera, including the digestive systems with the liver and also the spleen. In addition to the veins, the labelling, in Arabic and Persian, includes the duodenum al-ithna ʿashar, the jejunum al-ṣa’im, the Ileum daqīq, the appendix ‘a’war, the colon qawlūn and the rectum mustaqīm. But the drawing in Figure 11 illustrates the arteries of the body, and includes the viscera, but only shows the labelling for the arteries. Mansur’s reputed anatomical illustration of a pregnant woman (Figure 12) is essentially his arterial figure on which a gravid uterus, with the foetus in a breech or transverse position, has been superimposed. According to Khalili et al., the fact that Manṣūr selected a drawing of arteries to demonstrate a gravid uterus may indirectly indicate that he regarded the fetoplacental unit as a part of the circulation. [12-13]

Figure 10: The veins and viscera diagram from Tashrīḥ-i badan-i insān by the 14th c. Manṣūr ibn Ilyās. (NLM, MS P 19) [12] |

Figure 11: The arteries diagram from Tashrīḥ-i badan-i insān – 14th c. Manṣūr ibn Ilyās (NLM manuscript MS P 19)[12] |

Figure 12: by the 14th-century Manṣūr ibn Muḥammad ibn Ilyās (folio 39b, NLM manuscript MS P 18) [12] |

Chronologically, the next famous gravid-uterus anatomical drawing was sketched a hundred years later by Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519). Da Vinci’s drawing is obviously more sophisticated, realistic and artistic; however, it still shows the foetus in a breech presentation (Figure 13).

Figure 13: A close-up from a page showing Leonardo’s study of a foetus in the womb (c.1510), Royal Library, Windsor Castle.

Therefore, the whole-body anatomical diagrams of the 14th-century Manṣūr Ibn Ilyās represent a step in the further evolution of anatomical drawings, a step that preceded the famous, magnificent whole-body drawings of the 16th-century Vesalius in his reputed De Fabrica Humanis Corporis.

1 / 5. Votes 89

No votes so far! Be the first to rate this post.

Muslim Heritage:

Send us your e-mail address to be informed about our work.

This Website MuslimHeritage.com is owned by FSTC Ltd and managed by the Foundation for Science, Technology and Civilisation, UK (FSTCUK), a British charity number 1158509.

© Copyright FSTC Ltd 2002-2020. All Rights Reserved.