This paper examines two eighteenth-century letters penned by English travellers to the provinces of the Ottoman sultanate who recorded the procedure of inoculation practiced widely by old women in response to the smallpox epidemic. Inoculation was a precursor to the smallpox vaccine developed by Edward Jenner in the late eighteenth-century.

Article Image banner by Jemo (©MidJourney CC BY-NC 4.0)

***

When Ṣā’id ibn al-Ḥasan (d. 1072), a medieval Christian doctor, lamented the faith that patients had in “senile old women” who, despite their “lack of intelligence”, were regarded as “more knowledgeable and of sounder opinion than the [male] physician” by patients, [1] he suggested that ‘learned medicine’ was the esoteric knowledge of male physicians. More significantly, however, he shed light on the contested position of female healers in medieval Muslim civilisation. Despite Ibn al-Ḥasan’s derisive characterisation of ‘old women’, Pormann has suggested that in “medieval Islamic and early modern European societies”, women were among the main practitioners of medical care in the form of “nurses and midwives” and “carers and curers”. [2] That “learned medical discourse” was saturated with male physicians certainly did not mean that female healers were excluded from practicing medicine—on the contrary, as Pormann contends, women embodied “potentially powerful competition” when set side by side with male physicians. [3] The same can be said of early modern Ottoman public health in the 18th century.

Two letters penned by eighteenth-century English travellers to the provinces of the Ottoman sultanate provide significant accounts of the widespread, largely female-led, practice of smallpox inoculation, indicating women’s public duty towards healthcare in Constantinople and various Arab regions of the Ottoman caliphate. Both letters—Lady Mary Montagu’s addressed to Sarah Chiswell (1717) and Patrick Russell’s to his brother Alexander (1767)—elucidate how the procedure was performed. Lady Mary (d. 1762), wife of the English Ambassador to Constantinople, is credited with introducing the prophylactic to England. Russell (d. 1805), as an English physician in Aleppo, carried out a broad study of the widespread practice of inoculation amongst the Arabs of the sultanate. [4] Due to the dearth of sources from female healers who performed the operation, contemporary epistles shed light on the procedure as observed by outsiders of the Ottoman lands.

Figure 2. Article Banner for “Women Dealing with Health during the Ottoman Reign” by Nil Sari – Source

Smallpox has been regarded as “one of the greatest scourges of mankind”, [5] as it was a deadly disease in the 18th century which also caused bodily scarring. [6] As the earliest prophylactic for the epidemic, inoculation involved the “transference of pustule fluid from a person with smallpox to … a healthy person”. [7] Old female healers who lived in the sultanate—also known as kocakarı— were known to “ritually administer” the procedure for smallpox. [8] In a letter that the English Ambassador’s wife addressed to Sarah Chiswell on the 1st April 1717, she describes the procedure:

“There is a set of old Women who make it their business to perform the Operation. Every Autumn in the month of September, when the great Heat is abated, people send to one another to know if any of their family has a mind to have the small pox. They make partys for this purpose, and when they are met (commonly 15 or 16 together) the old Woman comes with a nutshell full of the matter of the best sort of small-pox and asks what veins you please to have open’d. She immediately rips open that you offer to her with a large needle […] and puts into the vein as much venom as can lye upon the head of her needle […] and in this manner opens 4 or 5 veins. “[9]

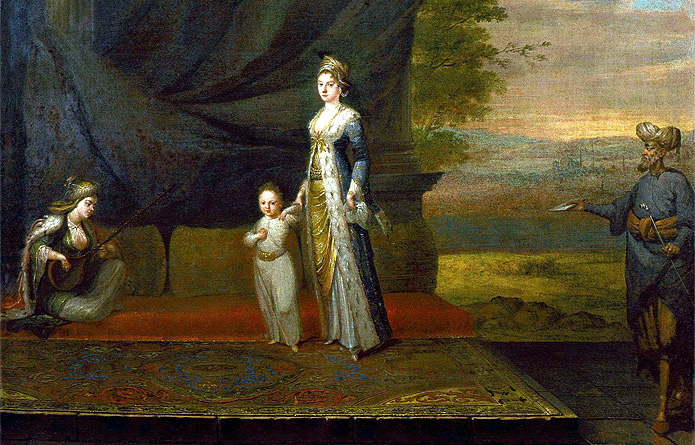

The following year, Lady Mary arranged for an “old woman” to administer the prophylactic on her child. [10] After requesting that the Embassy surgeon Charles Maitland (d. 1748) inoculate her young boy, on the 23rd March, Lady Mary’s letter to her husband records that their son Edward was “engrafted last Tuesday, and is at this time singing and playing and very impatient for his supper”.[11] Later in 1722, Maitland would depict the inoculator as an “old Greek Woman”. [12] Accordingly, what emerges from Lady Mary’s account is that inoculation was a “female concern”. [13]

Figure 3. Article Banner for “Lady Montagu and the Introduction of Smallpox Inoculation to England” – Source

Although Lady Mary’s Turkish Embassy Letters were printed posthumously in 1763 as Letters of Lady Mary Wortley Montague: Written during her Travels in Europe, Asia, and Africa, [14] the present study uses selected letters from Robert Halsband’s edition, The Complete Letters, published in three volumes between 1965-1967, as it contains the entirety of Lady Mary’s letters that have been found. [15] Her letters, however, were circulated during her lifetime with amendments from the original, [16] and consequently cannot be regarded as entirely reliable. Of the issues that emerge from historians studying the dilettante’s correspondence, there remains the fact that her letters were not ““purely” epistolary”—they are only a “re-imaging” of the initial letters which she revised copies upon coming back to England. [17] Halsband has commented that they are “a compilation of pseudo-letters”, contemplating whether they can be seen as a “travel-memoir”. [18] Nonetheless, the Turkish Embassy Letters remain a detailed and authoritative account of Lady Mary’s sojourn, [19] and there is no doubt that they were crafted for publication. [20] Following her demise in 1763, her epistolary correspondence would come into print “from an imperfect … manuscript” while her family were unaware—this would become the “basis of all editions”, only being rectified in 1861 “when the albums … were first used”. [21] For this reason, the Halsband edition is more useful than the first edition which was incomplete and based on unpolished originals, and is therefore used in this chapter.

However, there still remains an issue with Lady Mary’s letter to Sarah Chiswell, which was initially intended for Lady Mary’s father. [22] During the editing of her epistolary collection, she “reassigned” the original to another person. [23] Consequently, Lady Mary’s letters alone cannot be taken as the sole source for old women’s inoculation. Notwithstanding the limitations that emerge from the reliability of the source, her observations myopically focus on Constantinople where her son was ‘engrafted’.

Figure 4. Article Banner for “Muslim Female Physicians and Healthcare Providers in Islamic History” by Sharif Kaf al-Ghazal, Marium Husain – Source

Patrick Russell, per contra, paints a broader portrait by “interview[ing] women in the harems, their Bedouin servants” and merchants, observing “that inoculation was used almost everywhere outside the bigger cities such as Constantinople and Aleppo”. [24] Describing when he had visited a Turkish harem, Russell explains that an old Bedouin women corrected him on the method of ‘the operation’:

“an old Bedouin, who having heard me with great attention, assured the ladies, that my account was upon the whole a just one, only that I did not seem to well to understand the way of performing the operation, which she asserted should be done not with a lancet, but with a needle; she herself had received the disease in that manner, when a child […] adding moreover, that the practice was well known to the Arabs” [25]

Moreover, the procedure was termed “buying the small pox” [26] as the child undergoing the procedure would exchange foodstuffs such as “raisins, dates, [and] sugar plumbs” with the child bearing smallpox—asking “how many pocks he will give in exchange.” [27] Bedouins who were “employed in the service of the Harems” were less inclined to the procedure as “their children” were raised surrounded by Turks among whom inoculation was proscribed. [28] Although he did not travel outside of Aleppo, he confirmed from several Turkish merchants of Baghdad and Mosul that the prophylactic was common amongst Eastern Arabs too, and even practiced in the holy city of Mecca. [29] Similar to Lady Mary’s description in her 1717 letter, Russell illustrates that it was a customary practice to “give notice by a public crier” so that people could “have their children inoculated.” [30]

Russell’s letter was addressed to his half-brother Alexander, who became Physician to the Levant Company’s Factory in Aleppo in 1740.[31] When Alexander left his post in 1753, Russell would take his position for another eighteen years, and the brothers often wrote to each other. [32] This explains why Russell’s epistolary correspondence to his brother resembles a naturalist’s findings, for he was a “skilled naturalist” writing to a fellow physician who had spent thirteen years in Aleppo. [33] His observations are corroborated by first-hand information, not chance observation. Moreover, Russell rectifies Alexander’s claim in the preceding letter, dated April 18th 1768, who had stated that prior to his departure from Aleppo, he “hear[d] that it was practised amongst some of the Bedouins there”. [34] Reading from Russell’s letter, Alexander would later on give an address before the Royal Society, indicating that it held significance for the medical establishment. [35] Taken as a whole, both sources demonstrate women’s central role to the widespread administration of the smallpox prophylactic, suggesting that the procedure “was women’s business”. [36]

Figure 5. Article Banner for “Medical Philanthropism on the Pilgrimage Route: Rabia Gülnüş Sultan” by Fatima Sharif – Source

Engaging with historiography, the following section argues that these accounts evidence that female healers contributed to the formation of public health in Constantinople and various Ottoman cities. [37] Old women’s ‘engrafting’ in the eighteenth-century points towards the beginnings of Ottoman public health which preceded modern vaccination; however, a problem arises for historians in locating the untold narratives of female healers who operated outside of institutionalised hospitals and therefore, outside of the discourse of ‘learned medicine’. Lady Mary informs Chiswell that “every year thousands undergo this Operation”, [38] while the old Bedouin woman that Russell interviews “had in her time inoculated many”, [39] indicating that an early form of public health was forming which women were organically involved in. Unlike hospital salary lists, there are no recorded documents of wages for these female healers, and consequently, little information can be gauged from sources on their demographic.

Described as a “surgical procedure” by the historian Miri Shefer-Mossensohn [40], inoculation was a practice of folk medicine likely to have been a craft that was passed on from one to another through observation and practice. However, it was “not documented in medical texts and treatises”, nor was it a practice of “institutional medicine” in 18th century hospitals or centuries prior. [41] Moore, a historian writing in 1815, suggests that according to various sources, engrafting was of unknown origins, but an established procedure in Persia, Armenia, Georgia, and Greece. [42] A more common theory, particularly “of a Patriarch of Constantinople”, was that it originated in the Arabian deserts “where neither physicians nor priests officiated”, and would come to be “monopolised by old women.” [43] It has also been speculated that Circassian traders were responsible for bringing inoculation to the seventeenth-century Ottoman provinces; [44] more specifically, Circassian women who were engrafted during childhood are thought to have introduced the prophylactic procedure “to the court of the Sublime Porte”. [45] Inoculation was not only practiced by Muslim women, a fact attested to by an English physician residing in Aleppo. Edward Tarry recorded that in 1706 a sweeping smallpox epidemic hit the cities of Constantinople, Galata, and Pera, [46] where a “Greek woman, native of the Morea” engrafted 4000 people. [47] These were Constantinople’s suburbs where “European … personnel lived”—and indeed, Pera is where Lady Mary would live between 1717-18, overseeing her son’s inoculation by an old Greek woman. [48]

Despite the contested narratives on the origins of the practice in medical historiography, most of the scholarship on Ottoman healthcare is concerned with professional medicine and the origins of institutional medicine. [49] It has been posited that this is due to two reasons; firstly, source availability which points disproportionately towards professional medicine; [50] and secondly, the dismissal of folkloric medicine “as a valid domain for investigation.” [51] Although folk and traditional medicine addressed the medical needs of a large population which early modern hospitals did not have the capacity for, they were regarded pejoratively as “primitive”. [52] As hospital staff only administered healthcare for a small percentage, [53] most of the population of the vast Ottoman sultanate had no means of accessing physicians. [54] It is therefore problematic to attribute the emergence of Ottoman public health to the 19th century, as it disregards the precursor to Jenner’s (d. 1823) cowpox vaccine as a ‘primitive’ prophylactic—which, in 1796, he reformed. [55] Historians of Western medicine, on the other hand, assign to Lady Mary a pioneering role. [56] This historiographical dichotomy leaves a gap in the discourse of the emergence of Ottoman public health.

According to Thomas Kuhn’s conceptualisation of paradigms, inoculation would not become a “scientific revolution” until the late nineteenth-century, the moment that the paradigm shifted. [57] Thus, inoculation was first dismissed by the prevailing paradigm of humoral medicine from the second century and would have to wait for the late nineteenth-century to become a revolution in modern medical advancements. [58] Bozok suggests that historians may encounter multiple beginnings when uncovering the history of events; thus, the smallpox vaccine may have emerged at almost the same time in different geographies, several centuries apart. [59] However, the birth of public health in the dynasty was only marked when Ottoman modern medicine embraced medical education. [60] While the history of modern medicine attributes the cowpox/smallpox vaccine to Jenner, female healers who did not conform to the paradigm are given minimal recognition. Within Kuhn’s paradigm there is no place for female inoculators or pioneering women who operated before the 19th century ‘scientific revolution’.

Overall, this study has evidenced that old women played a pivotal role in the emergence of healthcare as demonstrated by their response to smallpox epidemics in the eighteenth-century Ottoman sultanate.

Figure 7. Article Banner for Book Review of ‘Ottoman Women – Myth and Reality’ by Asli Sancar – Source

[1] Ṣāʿid ibn al-Ḥasan, Stimulating a Yearning for Medicine (al-Tashwīq al-ṭibbī), ed. O. Spies, fol. 38a9-10, 13-14; German tr. Taschkandi, Übersetzung und Bearbeitung (Bonn: Selbstverlag des Orientalischen Seminars der Universität, 1968), 131, quoted in Pormann and Savage-Smith, Medieval Islamic Medicine, 103.

[2] Peter E. Pormann and Emilie Savage-Smith, Medieval Islamic Medicine (Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press, 2007), 103.

[3] Ibid., 103.

[4] Arthur Boylston, “The origins of inoculation,” Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine vol. 105,7 (2012): 311, doi:10.1258/jrsm.2012.12k044.

[5] A. M. Behbehani, “The Smallpox Story: Life and Death of an Old Disease,” Microbiological Reviews Vol. 47, no. 4 (1983): 455. See also: Crosby, Alfred W. “Smallpox.” In The Cambridge World History of Human Disease, edited by Kenneth F. Kiple, 1008–13. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993.

[6] Alicia Grant, Globalisation of Variolation: The Overlooked Origins of Immunity for Smallpox in the 18th Century (London: Word Scientific Publishing, 2019), 5.

[7] Ibid., 8.

[8] Sarı, Nil. “Osmanlı Sağlık Hayatında Kadının Yeri,” Yeni Tıp Tarihi Araştırmaları, 2–3 (1996–7): 11.

[9] Lady Mary Montagu, “To [Sarah Chiswell] 1 April [1717],” in The Complete Letters of Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, ed. Robert Halsband (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1965), 338-339.

[10] Gulten Dinc and Yesim Isil Ulman, “The introduction of variolation ‘A La Turca’ to the West by Lady Mary Montagu and Turkey’s contribution to this,” Vaccine 25, no. 21 (2007): 4264, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.02.076.

[11] Lady Mary, “To Wortley 23 March [1718],” 392.

[12] Charles Maitland, Mr Maitland’s Account of Inoculating the Small Pox (London: J. Downing, 1722), 6. https://nrs.lib.harvard.edu/urn-3:fhcl.hough:1255026.

[13] Isobel Grundy, “Montagu’s variolation,” Endeavor 24, no. 1 (2000): 5, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-9327(99)01244-2.

[14] P. Spedding, “Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, Manuscript Publication and the Vanity of Popular Applause,” Script & Print 33 (2009): 152.

[15] Robert Halsband, “Preface,” in The Complete Letters of Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, ed. Robert Halsband (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1965), v.

[16] R. Chung, “A Woman Triumphs: From Travels of an English Lady in Europe, Asia, and Africa (1763) by Lady Mary Wortley Montagu,” in Travel Knowledge: European “Discoveries” in the Early Modern Period, ed. I. Kamps, & J. G. Singh (New York: Palgrave, 2001), 111.

[17] Joseph W. Lew, “Lady Mary’s Portable Seraglio,” Eighteenth-Century Studies 24, no. 4 (1991): 433, https://doi.org/10.2307/2738966.

[18] Halsband, “Introduction,” in The Complete Letters of Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, ed. Robert Halsband (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1965), xiv.

[19] Ibid., xiv.

[20] Ibid., xvii.

[21] Ibid., xvii.

[22] Grundy, “Montagu’s variolation,” 5.

[23] Ibid., 5.

[24] Boylston, “The origins of inoculation,” 311.

[25] Patrick Russell and Alexander Russell, “An account of inoculation in Arabia, in a letter from Dr. Patrick Russell, Physician, at Aleppo, to Alexander Russell, M. D. F. R. S. preceded by a letter from Dr. Al. Russell, to the Earl of Morton. P. R. S,” Phil. Trans. R. Soc Vol. 58 (1768): 142, https://doi.org/10.1098/rstl.1768.0020.

[26] Ibid., 143.

[27] Ibid., 143.

[28] Ibid., 144.

[29] Ibid., 146.

[30] Ibid., 144.

[31] B.J. Hawgood, “The life and viper of Dr Patrick Russell MD FRS (1727–1805): Physician and naturalist,” Toxicon. 32, no. 11 (1994): 1296, doi:10.1016/0041-0101(94)90402-2.

[32] Ibid., 1296.

[33] Ibid., 1296.

[34] Alexander Russell, “inoculation in Arabia,” 140.

[35] Hawgood, “The life and viper,” 1296.

[36] Michael Bennett, “Jenner’s Ladies: Women and Vaccination against Smallpox in Early Nineteenth-Century Britain,” History 93, no. 4 (312) (2008): 500, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24428855.

[37] Ibid., 500.

[38] Lady Mary, “1 April [1717],” 339.

[39] Patrick Russell, “inoculation in Arabia,” 142.

[40] Miri Shefer-Mossensohn, “Medicine in the Ottoman Empire,” in Selin, H. (eds) Encyclopaedia of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine in Non-Western Cultures. Springer Dordrecht, 2016: 3052, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-7747-7_10138.

[41] Rhoads Murphey, “Ottoman Medicine and Transculturalism from the Sixteenth Through the Eighteenth Century,” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 66, no. 3 (1992): 381, http://www.jstor.org/stable/44442674.

[42] J. C. Moore, A History of the Smallpox (London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme and Brown, Paternoster-Row, 1815), 223.

[43] Ibid., 223.

[44] Stefan Riedel, “Edward Jenner and the history of smallpox and vaccination,” Proceedings (Baylor University. Medical Center) Vol. 18,1 (2005): 22, doi:10.1080/08998280.2005.11928028.

[45] Ibid., 22.

[46] Moore, A History of the Smallpox, 230.

[47] Ibid., 230-31. A copy of this letter is available: Tarry letter, August », 1721, to Sir Hans Sloane, Sloane MSS. (British Museum) 4061, f. 164.

[48] Genevieve Miller, The Adoption of Inoculation for Smallpox in England and France (London: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1957), 50.

[49] Murphey, “Ottoman Medicine and Transculturalism,” 381.

[50] Ibid., 382.

[51] Ibid., 382.

[52] Ibid., 382.

[53] Ibid., 382.

[54] Ibid., 382.

[55] Grant, Globalisation of Variolation, 8.

[56] Although there has been a more recent trend in historiography downplaying her major role. See: Genevieve Miller, “Putting Lady Mary in Her Place”.

[57] T. Kuhn, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (Chicago: University of Chicago, 1970), 92. See Kuhn: p. 176. A paradigm can be defined as established hypotheses at a particular time in history.

[58] Grant, Globalisation of Variolation, 8.

[59] Nihan Bozok, “Avrupalı Cadıların Bostanları, İstanbullu Kocakarıların Çiçek Aşısı ve Cinchon Kontesinin Kınakına Ağaçları: Modern Tıp Tarihi Kadınları Neden Yazmadı?” Fe Dergi 10, no. 1 (2018): 144, https://doi.org/10.1501/Fe0001_0000000203.

[60] Ibid., 144.

3.6 / 5. Votes 5

No votes so far! Be the first to rate this post.

Muslim Heritage:

Send us your e-mail address to be informed about our work.

This Website MuslimHeritage.com is owned by FSTC Ltd and managed by the Foundation for Science, Technology and Civilisation, UK (FSTCUK), a British charity number 1158509.

© Copyright FSTC Ltd 2002-2020. All Rights Reserved.