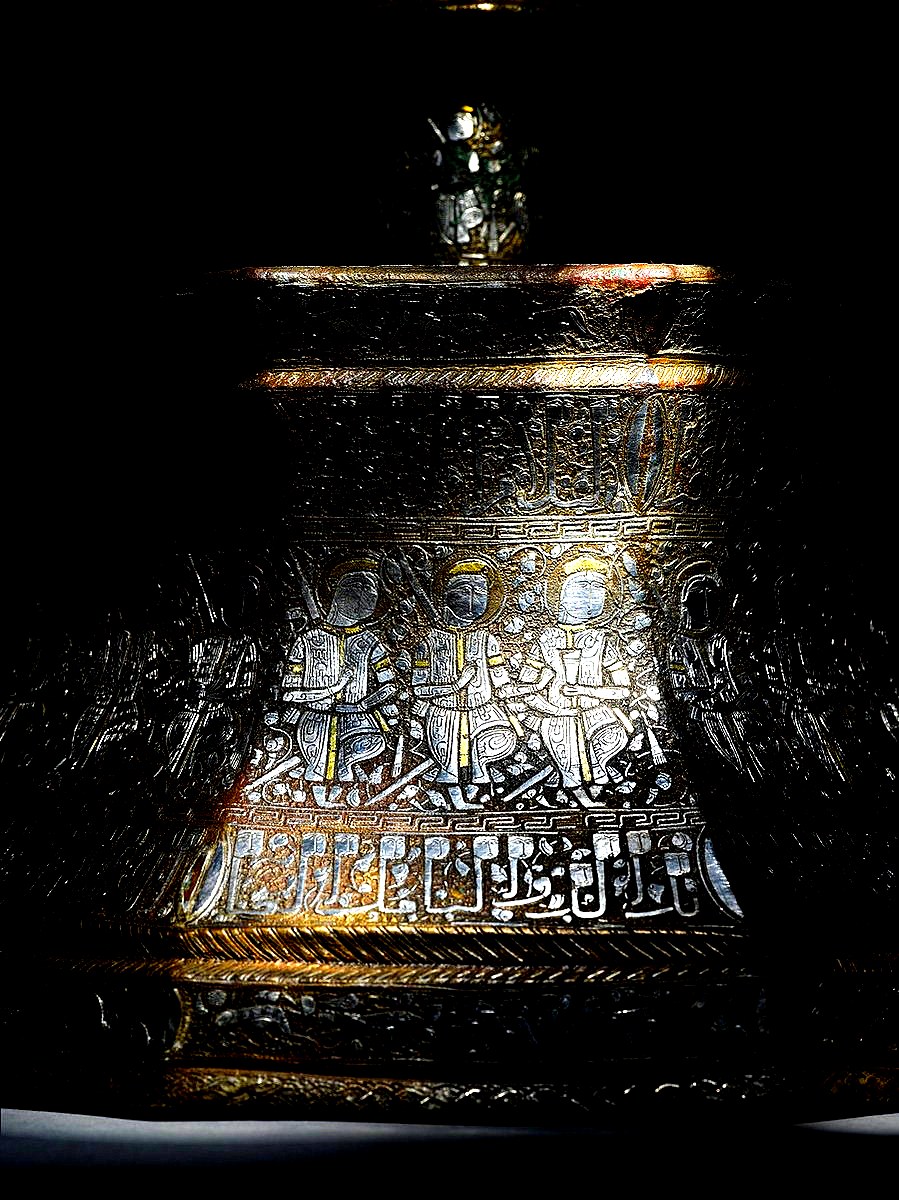

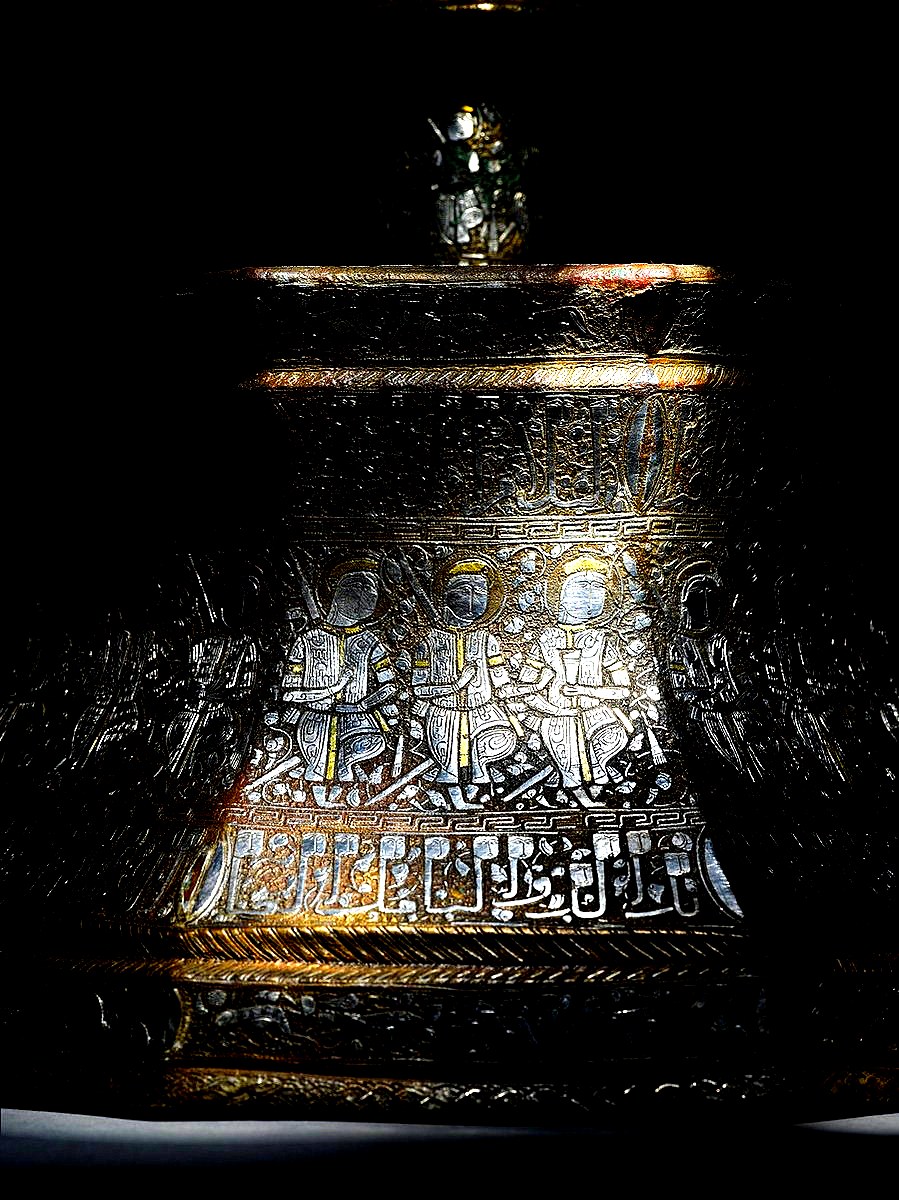

A 13th-century silver-inlaid brass candlestick, attributed to the Mosul school of metalwork, broke Sotheby’s record for an Islamic art object when it sold for $9.1 million following a 25-minute bidding contest during the Arts of the Islamic World & India auction in October 2021.

Figure 1. A member of staff is looking at the gold and silver-inlaid brass candlestick base at Sotheby’s in London, Friday, Oct. 22, 2021. The candlestick base is part of the Sotheby’s Arts of the Islamic World and India and will go on auction on 27th October for an estimate of £2 – 3 million. (AP Photo / Alberto Pezzali – thenationalnews.com)

***

Note of the Editor: This article was first composed by Cem Nizamoglu for 1001 Inventions, 17 December 2021, website and now updated for the Muslim Heritage website.

***

“…the extended bidding had captivated the saleroom until the hammer fell on the record price”*

Figure 2. The silver-inlaid brass candlestick, which was made in Northern Iraq circa 1275, soared to $9.1 million. (arabnews.com)

As arabnews.com and thenationalnews.com reported, a 13th-century silver-inlaid brass candlestick, produced in Northern Iraq (most likely Mosul) around 1275 CE, sold at Sotheby’s London on October 28, 2021, breaking all previous records for an Islamic object at auction with a final price of $9.1 million (£6.6 million).

Its price surpassed that of the prior record-holder, the famous Turkish “Debbane Charger“, a 15th-century Iznik ceramic plate, which fetched $6.9 million in 2018.

One of only a handful of major metal masterpieces from Iraq and Syria celebrated inlaid brass tradition, this candlestick base is especially notable for its:

Grand size (~26 cm tall × 30 cm diameter)

Continuous figural frieze featuring courtly figures, musicians, and running animals

Rich detail in silver and gold inlay

The artefact had remained in a European private collection since the 1960s and was recently exhibited at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York .

Sotheby’s hailed it as:

“the finest example of Islamic metalwork to appear on the market in over ten years“.

Figure 3. An exceptional gold and silver-inlaid brass candlestick base, probably Mosul, circa 1275, (Sotheby’s)

Inscriptions on the candlestick base:

“Perpetual Glory and Safe Life and Increasing Prosperity and Perfect Good-fortune, Well-being, Dominant Command, Generosity, Agreeable Wealth, Safe Good-fortune and Increasing Prosperity and Perfect Good-fortune, Well-being… Command”

*Sotheby’s said the extended bidding had:

“…captivated the saleroom”

, until the hammer fell on the record price. Sotheby’s chairman for the Middle East and India told The National the figure was:

“…fully justified”

, calling the piece:

“…the best of the best”

Edward Gibbs, Chairman, Head of Department, Middle East and India, Sotheby’s, said:

“The results reflect the health of the market-driven by strong demand for top pieces. The silver and the gold-inlaid candlestick was the best of its kind: rare and beautiful and of a quality worthy of a major museum,”

Figure 4. Chandelier or Candlestick base (Iraq, Mosul – Aleppo, Syria), 1248-49, Louvre AD 4414, attributed to Dāwūd ibn Salāma al-Mawṣilī, inscribed: “longevity, happiness, splendour, benefits, praise.” (Wikimedia)

Iran, Syria, Egypt, and Iraq emerged as principal centres of luxury metalcraft during the early 13th century, when Arabic and Turkic artisans elevated silver-inlaid brassware to new artistic heights. This period marked the flourishing of an elite metalworking tradition, with intricately crafted objects commissioned by aristocrats, merchants, and rulers across the Islamic world. These works, often bearing inscriptions, figural scenes, and courtly motifs, reflected not only exceptional technical skill but also the cultural prestige and cosmopolitan tastes of their patrons.

Important figures associated with the Islamic metalworking tradition during the Golden Age of Islam include master artisans such asʿAlī al-Sankarī al-Mawṣilī, whose 13th-14th century candlestick base remains a celebrated example of Mosul craftsmanship. Artisans from Mosul, Herat, Damascus, and Cairo developed highly refined techniques of inlaying silver and gold into brass, often inscribing their names, workshops, and patron dedications directly onto the objects, transforming utilitarian pieces into signed works of art.

Notable names include:

Ahmad al-Dhaki al-Mawsili, a 13th-century artisan renowned for producing inlaid brasswares in Mosul for Ayyubid and Mamluk elites.

Muhammad ibn al-Zayn, the craftsman of the celebrated Baptistère de Saint Louis (ca. 1300), a masterpiece of Mamluk metalwork now housed at the Louvre, blending Islamic and crusader-era imagery with exquisite technical sophistication.

ʿAbd al-Qadir al-Hisari, an artisan active in 14th-century Egypt, was known for his richly decorated basins and candlesticks, many of which were inscribed with Qur’anic verses and poetic inscriptions.

Active: 13th century, Mosul

Known for exceptional inlaid brasswork with rich epigraphic decoration.

His works are held in several European museum collections.

Often signed his name as a mark of pride and authenticity.

Active: 13th century

Possibly a relative or apprentice of Shujaʿ ibn Manʿa.

Produced elegant vessels with scenes of hunting, feasting, and courtly life.

Active: Late 13th to early 14th century

Specialising in producing intricately decorated incense burners and trays.

Often featured Kufic inscriptions and zodiacal symbols.

Region: Egypt/Syria, Mamluk period

Known for candlesticks and basins made during the early 14th century.

One example is inscribed with his name and the name of the Mamluk Sultan al-Nasir Muhammad.

Active: Late 13th century, Syria

Master metalworker; examples of his work feature Quranic inscriptions, often combined with astrological themes.

Known for a safina (inkstand) with medallion inscriptions and foliate scrolls.

Active in the Mosul region, where Islamic metalwork peaked before being disrupted by the Mongol invasions.

Arabic and Turkic brassworks are distinguished by their style and Innovation:

These works often feature distinctive motifs, such as octagonal geometric emblems, arabesques, medallions, and rosettes. Over time, these elements became recognisable “brand marks” of Arabic and Turkic craftsmanship, symbolising not only artistic mastery but also the cultural synthesis between nomadic and urban traditions across the Islamic world. The intricate iconography, ranging from astrological signs and mythological beasts to scenes of courtly life, offers insight into the intellectual and cosmopolitan climate of the time.

There are several more renowned figures in the tradition of Islamic metalwork, particularly from the 12th to 14th centuries, when the art of inlaid brasswork, silver, and gold decoration flourished in centres like Mosul, Damascus, Cairo, Herat, and Khorasan. While only a limited number of artisans signed their work, several names have survived on inscriptions, particularly due to their elite patrons and the wide circulation of their masterpieces.

Monumental scale and bold figural decoration

High precision in silver and gold inlay

Continuous inscriptions featuring benedictory prayers and praises.

Legacy of Arabic and Turkic metalwork influenced subsequent metalworking traditions, especially in Turkic Mamluk Syria and Egypt, as Mosuli and Aleppo artisans migrated or their stylistic influence spread westward in the later 13th century.

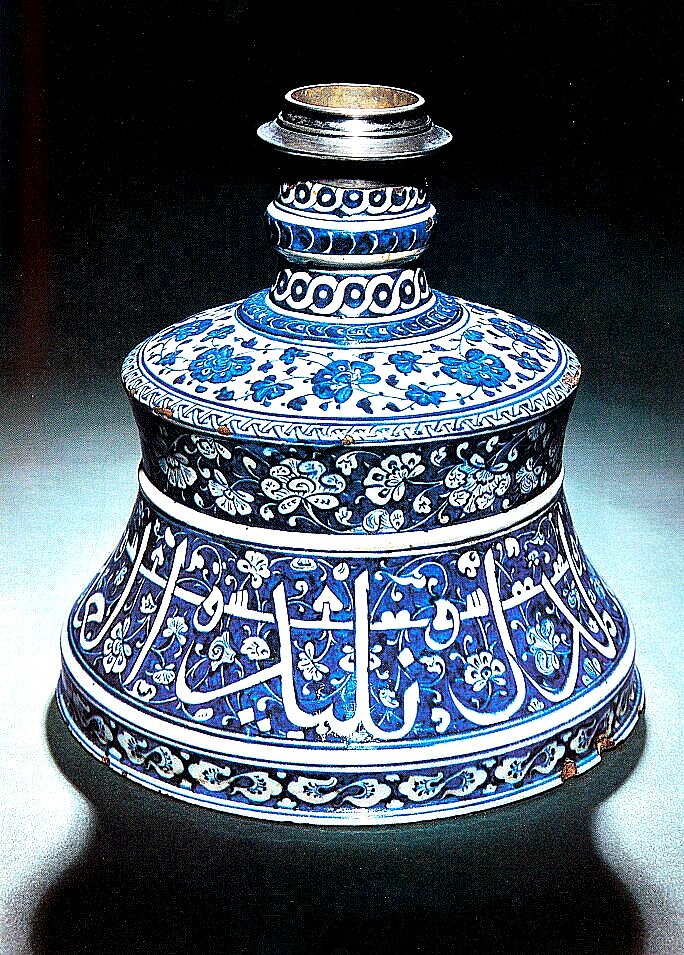

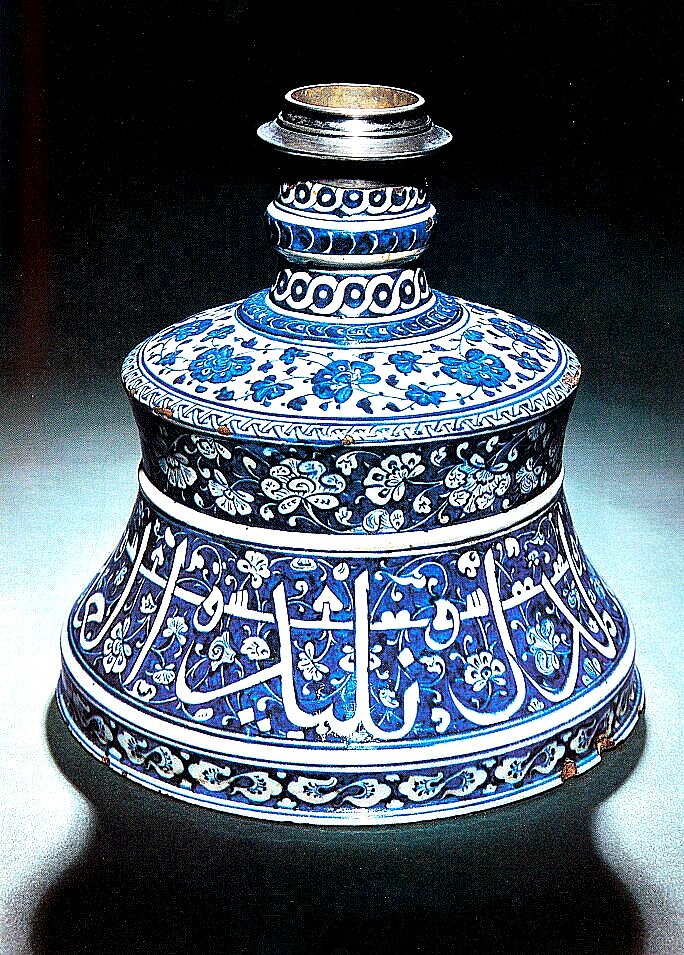

Figure 5. An Iznik blue and white pottery candlestick, Turkey, circa 1480. Sold at Sotheby’s, 29 April 1993, for £617,500.

In May 1993, another extraordinary Islamic artefact came to public attention when a pottery candlestick base achieved a record-breaking auction price at Sotheby’s. As reported by Independent.co.uk under the headline:

“Islamic candlestick sets record: Discovery of medieval Turkish artefact”

The piece, a blue-and-white ceramic candlestick base, was originally deposited at the Regent Street branch of the TSB Bank as collateral for a loan. Expected to sell for approximately £200,000, it ultimately realised £617,500 at auction, setting a new record for Islamic art at the time.

Scholars quickly identified the object as one of the earliest known products of the Ottoman potteries at Iznik, located approximately 60 miles southeast of Istanbul and active from around 1480. The candlestick base had been mentioned in a 1903 publication, which placed it in a French collection, but it had since vanished from scholarly view. Its rediscovery generated significant excitement in the field of Islamic art.

The candlestick’s importance lies not only in its monetary value but also in its role in early Ottoman ceramic history. It reflects the fusion of Turkic aesthetic traditions with broader Islamic artistic influences, signalling the emergence of Iznik as a major centre for ceramic innovation in the Islamic world.

Dr. John Carswell, a leading Islamic art specialist at Sotheby’s, remarked:

“To walk into a local bank and get shown the piece was like finding a lost Rembrandt”

Figure 6. Artuqid Candlestick base, now in the Islamic Museum, al-Aqsa Mosque / al-Haram al-Sharif, Jerusalem, Palestine. Belongs to Artuq Arslan Ibn Ilghazi Ibn Artuq, ruled in Mardin, Turkiye around the 13th Century, then, he seceded to his son, Najm al-Din Ghazi, Artuqid Dynasty, Turkish Anatolian Beylik (Principality) of the Seljuk Empire. Copper inlaid with gold and silver. formed with hammering and carving. The body of the candlestick base is adorned with a series of arches supported by pillars that have bases and capitals, and all of which are embossed and in high relief. Within these arches there is an inscription band that has been engraved and inlaid with silver in large thuluth script, it reads: “Strength to our master, the sovereign ruler, the just, the helper, the victorious, the triumphant, protector of the world and religion, leader of Islam and Muslims, Artuq Arslan Ibn Ilghazi Ibn Artuq, commander of the faithful, May God prolong his life and strengthen his victory.” islamicart.museumwnf.org

Nearly every object produced within Muslim civilisation carries with it a unique story, shaped by the exceptional craftsmanship invested in its creation, often requiring months or even years to complete. These artefacts were more than functional items; they were imbued with personal, religious, cultural, and symbolic significance. Some were immortalised in prayers, poetry and legends, others passed down through family wills for generations, and many were exchanged as diplomatic gifts or displayed as ornaments in the palaces of rulers. Such objects functioned not merely as tools but as vessels of memory, markers of identity, and expressions of pride. A particularly evocative example from the 14th century is the famed candlestick of ʿAlī al-Sankarī al-Mawṣilī, which was said to have “spoken” these words:

“I was made for the assemblies of the great,

and I shone in the night like the full moon.

When knowledge gathered in the courts,

I stood as its witness,

burning not only with flame,

but with honour.”

This poetic inscription not only reflects the artistry of Islamic metalwork but also the cultural reverence for objects as expressions of learning, status, and spiritual light:

“I carry the flame,

and its repeated flickers.

Dress me in yellow garments.

I never attend a majlis (seat of a government),

Without lending the night the raiment of the day”

(Source)

Although in many Islamic cultures, candlestick bases were a standard fixture in both religious and funerary architecture, particularly positioned to flank the mihrab (the niche indicating the direction of prayer) in mosques and tombs. Interestingly, these candlestick bases were not always intended for functional illumination; often, they were symbolic objects, with candles left unlit for ceremonial or aesthetic purposes. In Ottoman Turkey, the use of gold in religious settings was theologically restricted by the clergy, who deemed it appropriate solely for the two holiest sites in Islam: the Haram (forbidden or unlawful) in Mecca and the Prophet Muhammad’s Mosque in Medina. As a result, Ottoman artisans turned to copper and tombak (a gilded copper alloy), which they developed into a refined art form during the late 16th and 17th centuries. These materials were employed in the production of both liturgical furnishings and a broad array of domestic vessels, reflecting a balance between opulence, theological restraint, and artisanal sophistication.

Figure 7-9. A large brass candlestick base, Syria or Iraq, 14th Century (Image Source), Brass; cast, engraved candlestick base Iraq or Iran, 14th Century (Image Source), Silver-gold inlaid brass Candlestick Base, Iraq, 14th Century (Image Source)

***

Figure 10-12. Fine brassware 12-sided candlestick base, Iran, 1220-1240 (Image Source), Brass, inlaid, copper-silver Candlestick Base, Iran, 12-13th Century (Image Source), Brass, engraved, gold-silver and black substance inlaid Iraq, 14th Century (Image Source)

***

Figure 13. Candlestick base with lion protomes, 12th-13th century, cast bronze, engraved decoration, openwork decoration, most likely from the Turkic Seljuq Empire, Khorasan, Iran, Louvre MAO 357 – (Wikimedia)

***

Figure 14. Candlestick of Sultan Hajji II (Al-Salih Hajji), a Turkic Mamluk Ruler, 1380-90 (14th century), Egypt, Louvre AOR 41/96 ; 96, This ornate candlestick is attributed to the reign of Sultan al-Ṣāliḥ Ḥājjī II, a Turkic Mamluk ruler of late 14th-century Egypt. It showcases the refined metalworking techniques of the Mamluk court, where such objects served both utilitarian and ceremonial functions. The candlestick was recovered after World War II by the Office of Private Property and Interests and is currently held under the French government’s MNR (Musées Nationaux Récupération) category, awaiting restitution to its rightful owner. (Wikimedia)

***

Figure 15. Embossed Candlestick base, 12th century, Iran, Nishapur, most likely Turkic Seljuq Empire, The Met Fifth Avenue in Gallery 453, stonepaste; applied decoration, monochrome painted under turquoise glaze this object was found in one of the upper levels of the mosque in the Tepe Madrasa area (Madrasa-i Tepe. Nishapur, Iran), and was probably used next to the mihrab. (Wikimedia),

Figure 16. Lamp or Candlestick base , 15th century AD, Iran or Central Asia, Most likely Turkic-Mongolian Timurid dynasty, Khalili Collection Islamic Art MTW 1531, copper alloy, cast and turned, The bulbous head of this candlestick base most probably served as the reservoir of an oil lamp. There are two such lamps, both dedicated by Timur, in the shrine of Ahmad Yasavi at Gorod Turkistan in Kazakhstan, one signed by the craftsman Taj al-Din Isfahani in 799 AH (1396–7 AD) and the other by his son, ‘Izz al-Din Isfahani, made on 20 Ramadan 799 (17 June 1397). The Muslim day ran from nightfall to nightfall, so that Sufi rituals associated with particular feasts always took place in the evening. In endowment deeds, considerable sums are set aside for wax, oil and other substances to light the buildings for these purposes, as well as costly lamps and candlesticks (chiraghdan). They were kept in a special store, the chiraghkhanah, with a guardian who was often well rewarded for his duties (Wikimedia),

Figure 17. Duck Candlestick (monumental candlestick with ducks), Iran, Khorasan,1150-1200, Louvre OA6315, Inscription:

“Safety and pleasure and completeness / and contentment and completeness and the paternal aunt (the blessing) and / and well-being and thanks and gratitude and dignity and intercession and blessing and perpetuity and the state and safety and happiness and completeness, and paternal aunt and health and survival for its owner…” (Wikimedia)

***

Figure 18. Candlestick of Glory, Met Museum 91.1.596 Inscription: In Arabic in band (Wikimedia) translation:

“Glory, Permanency, Piety, Munificence, Victory, Power”

Translation by Yassir al-Tabba (1978), top:

“Glory, continuance, thank God… alms, giving, generosity, magnificence, defeat of enemies, longevity, elevation, ascendance and lasting dominion –

Bottom:

Glory, continuance, thank God … thank, magnificence, defeat of enemies, longevity, elevation, ascendance, lasting dominion … security, elevation, and command”

Kufic inscription illegible (Wikimedia)

***

Figure 19. Guardian of the Sultan’s Seat Candlestick base, late 13th–first half 14th century. In the medallions decorating this candlestick base, sits a ruler on a lion‑throne with harpies and attendants, and figures holding a crescent personifying the Moon. Arabic inscriptions around the base and neck wish the owner well and list his princely titles, reinforcing the themes of royal authority and prosperity conveyed in the imagery, Met Museum 91.1.523 Most notably, the candlestick base bears the inscription al-Faris Aqtaya Amir Majlis in a style that is found in Ayyubid and Zangid metalwork, often applied to denote later owners, and a similar inscription is also found on the Boston example. The phrase Amir Majlis was a Mamluk title meaning ‘Guardian of the (Sultan’s) Seat’, and there are two figures named al-Faris Aqtaya corresponding with the latter part of the Ayyubid and early Mamluk rule under al-Malik al-Salih (r.1240-49), both possible owners of this candlestick base. (Sotheby’s) Inscriptions in Arabic are enclosed by bands extending around the socket, the base of the neck, the shoulder, and the main body of the candlestick. These are blessings for the anonymous sultan to whom this work was dedicated and include words such as “glory,” “triumph,” “prosperity,” “fortune,” and “long life.” In addition, a brief section of an invocation (due’a) in verse on the shoulder, now partly erased, was commonly found on contemporary metalwork in the Iranian area. Yet another, later inscription states that the candlestick base belonged to a certain “Zaynab, the daughter of the Commander of the Faithful, al-Mahdi li-din allah.” (Wikimedia)

***

Figure 20. Egyptian Candlestick Base – Walters 54459, Throughout Islamic history, sultans, princes, and court officials have been active art patrons. This impressive candlestick base was commissioned by Zayn al-Din Kitbugha, who served as saqi or cupbearer, at the court of the Turkic Mamluk Dynasty in Egypt before ascending the throne in 1294. The large inscription in thuluth script around the candlestick’s body is punctuated by roundels featuring a stemmed cup, Kitbugha‘s blazon, or heraldic shield. Calligraphy is also a major decorative element. In addition to the large thuluth inscription, this piece includes different sizes and styles of Arabic script. Despite its elaborate design, Kitbugha had the candlestick base made for use in his household storeroom or pantry. The candlestick’s neck and socket- today in the Museum of Islamic Art, Cairo- already had been removed when Henry Walters,1925 added the piece to his growing collection of Islamic art. [Transcription] Inscribed base and neck: Zayn al-Din Kitbugha; (Wikimedia 01–02–03) [Translation] Inscribed base in thuluth script:

“This is one of the things made for the servery of the lofty authority, the lordly, the great amir, the conqueror, the holy warrior, the just, al-Zayni, Zayn al-Din Kitbugha al-Mansuri al-Ashrafi (of the households of the sultans Qalawun and Khalil)”

***

Figure 21. Pair of Dragon-headed Candlesticks, brass, piece cast and turned, MTW 937 (Nasser D. Khalili Collection of Islamic Art), 15th century AD, Khurasan, perhaps Herat, or Central Asia, most likely Turkic-Mongolian Timurid Empire; The dragon-head candle sockets suggest Timurid associations. The bell-shaped bases, on the other hand, are much closer to Mamluk candlesticks than to traditional Iranian shapes and probably reflect the work of Syrian craftsmen deported by Timur when he sacked Damascus in 1393 and sent them to work on his buildings in Central Asia. Three such candlesticks bear dates between 1467 and 1488, but there is one in the shrine of the Sufi saint Ahmad Yasavi at Gorod Turkistan in Kazakhstan, dedicated by Timur, who restored the shrine in 1397 (Wikimedia)

5 / 5. Votes 2

No votes so far! Be the first to rate this post.

Muslim Heritage:

Send us your e-mail address to be informed about our work.

This Website MuslimHeritage.com is owned by FSTC Ltd and managed by the Foundation for Science, Technology and Civilisation, UK (FSTCUK), a British charity number 1158509.

© Copyright FSTC Ltd 2002-2020. All Rights Reserved.