Some medical historians of the last century mistakenly recorded that Caesarean section was strictly forbidden amongst Muslims. This opinion has been repeatedly quoted without examining its authenticity or validity. Research into available ancient Arabic sources can lead to evidence contrary to such a view. The Islamic scholars of the Middle ages were, in fact, the first to not only write about this operation but to illustrate it in pictures and describe it in poetry. Considering the antiquity of their time, it is unfair to compare them with scholars of a later date; but their achievements must be valued.

Table of contents

1. Introduction

2. The debate in historical sources

3. The legacy of Islamic medicine

4. The evidence from Islamic historical sources

5. Conclusion

6. Notes and references

Note of the editor

This article was first published in the Saudi Medical Journal 1986; 7 (1): 21-25. We are grateful to the author for allowing publication in www.MuslimHeritage.com.

* * *

Some medical historians of the last century mistakenly recorded that Caesarean section was strictly forbidden amongst Muslims. This opinion has been repeatedly quoted without examining its authenticity or validity. Research into available ancient Arabic sources can lead to evidence contrary to such a view. The Islamic scholars of the Middle ages were, in fact, the first to not only write about this operation but to illustrate it in pictures and describe it in poetry. Considering the antiquity of their time, it is unfair to compare them with scholars of a later date; but their achievements must be valued.

|

|

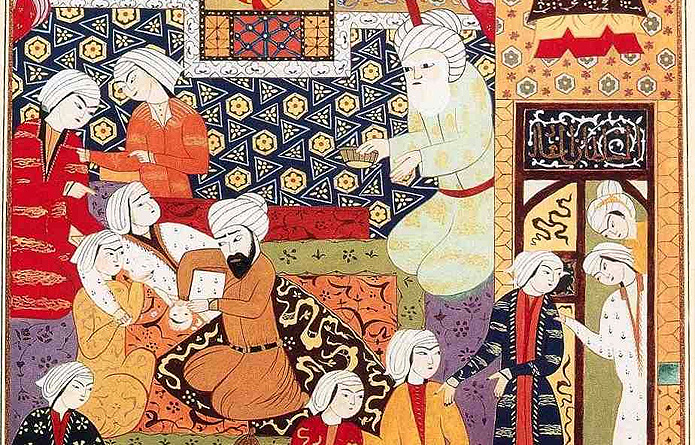

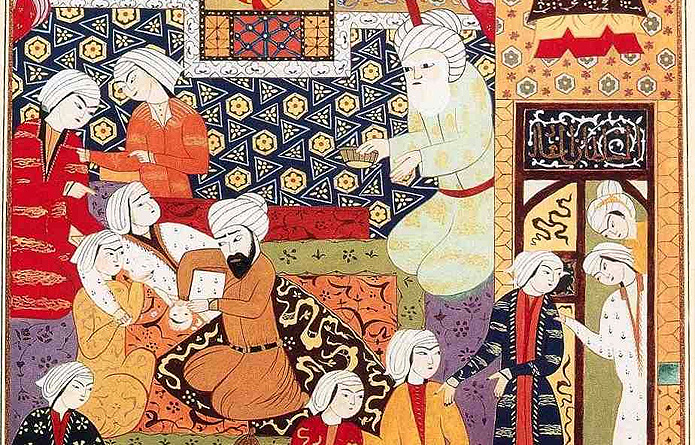

Figure 1: A miniature page of al-Firdawsî’s Shahnama indicating the birth of Rustam. Source: Topkapi Palace Library, MS H 1479. |

2. The debate in historical sources

During the middle of the last century, some medical historians erroneously recorded that Arab authorities in the Middle Ages discouraged surgical advances in general and particularly prohibited the operation of Caesarean section. Since then this view has been quoted without questioning its validity. One reference regarding Caesarean section quoted repeatedly came from a French army doctor. In 1863, C. Rique wrote about medical legislation in Arabia [1]. He mentioned that post-mortem Caesarean section was strictly forbidden by Sidi Khalif, whose opinion carried great weight in matters of casuistry among Muslims. The author did not take care to establish the authority of Sidi Khalif, who is unknown in Arabic literature. Moreover the opinion of one nineteenth century person cannot be applied retrospectively to medical practices of earlier periods and it is unfortunate that Rique’s view has often been quoted as applicable throughout Arabian medical history.

In 1944 Young in his History of Caesarean Section wrote: ‘Mohammedanism absolutely forbids it, (Caesarean section) and directs that any child so born must be slain forthwith as it is the offspring of the Devil’ [2]. This statement matches what Rique had said, but has been quoted without reference to any original source. A more modern example comes from Wright who also wrote that the Muslim religion absolutely forbade this operation [3]. This opinion was again expressed without any supporting evidence, but vaguely argued that this operation had not been mentioned in the writings of some of the great Arabic physicians of the Middle Ages. But in the same paragraph the author also stated that neither had any of the great European medical writers mentioned this operation, for example Eucharius Röslin in the famous Rosegarten published in 1513.

3. The legacy of Islamic medicine

In order to study the medical history of the period it is important to keep in mind that we are dealing with a period more than half a millennium before the European Renaissance. Professor Ullmann, a contemporary author of Arab medical history has expressed this better ‘Islamic medicine is the discipline of a period which knew no renaissance and no enlightenment, one must therefore be careful not to measure it with the same yardstick that one would apply to the history of European discipline’ [4]. Such a view is further strengthened when we remember that this operation remained highly controversial in Europe until the eighteenth century, and that the first successful Caesarean section in England was not performed until 1793 [5].

Due to a lack of source material, some historians relied on works unrelated to medical history, such as the story of a slave girl Tawaddud from the ‘Arabian Nights’. The literary value of such a classic deserves due appreciation but it cannot take the place of serious medical or scientific works. Unfortunately, these weak references are still cited, ignoring information which has come to light. For example, it is now known that Yuhanna Ibn-Masawayh (777-857 CE) who was personal physician to Al-Ma’mun, used to dissect apes to learn anatomy [6].

It is accepted that there is a scarcity of source material, and books covering ancient Arab medical history are rare and unexplored. Relevant literature is not only scanty but scattered, fragmented and unedited. This view was expressed by the eminent Arabist E.G. Brown in 1922 and remains true to this day [7]. In spite of this handicap, if we confine ourselves to a fairly early period of Arab pursuit of knowledge, we come across some convincing evidence regarding Caesarean section. This evidence forces us to review the argument and come to the conclusion that the operation was known to Arabs, that they wrote about it and it was practised in the lands under their influence.

Arabs had three major sources available to them from which they could enlighten themselves regarding this interesting operation. Firstly, they had a close association and extremely cordial relationships with Jewish scholars of the period. Many of them contributed original material and took part in translating Greek and Latin medical literature into Arabic. It is a fact that the best known translators of the time were Jewish. They must also have transferred the Talmudic references about Caesarean section [8]. The second source of such knowledge could be from Roman history. During Roman times post-mortem Caesarean section was widely practised and governed by royal decree of King Pompilius (715-673 BCE) known as King’s Law or Lex Regia [9]. Lastly, probably the most important and richest source available to Arabs regarding this operation was from Indian doctors. Post-mortem Caesarean section was known and practised by Indians many centuries before Islam. The famous Indian medical authority Susruta wrote about the operation dating the fifth century BCE. It is also well established that during the period when Arabs were translating medical works. Indian doctors were employed to translate Indian books into Arabic. Ullmann tells us that Barmakīd Yahyū Ibn Khālid commissioned an Indian doctor Mankah to translate Susruta into Arabic. It is worth mentioning that the same Mankah also translated another Indian work into Arabic, entitled Kitāb-al-Sumūm, or the Book of Poisons, the original source of which is still unknown.

There is ample evidence that Indian doctors were associated with Arabic medical practice for a long time during the golden period of Arab progress. Indeed the Arabic word for pharmacy was actually derived from an Indian source [10]. Under these circumstances it is inconceivable that the concept of such an important operation would not have been introduced into Arab medical practice. This speculation about Indian influence may be further strengthened if one considers that practically all references relating to this operation originated in the eastern Caliphate or the area under the influence of Baghdad. It has not been mentioned by scholars of the western Caliphate or by the Arabs of Spanish origin. The most important surgical authority Abū al-Qāsim bin Abbās Al-Zahrāwī of Cordova who died in 1013 CE did not mention this operation although he devoted a full section to operative obstetrics in the 30 volumes of his Tasrīf [11].

4. The evidence from Islamic historical sources

But the most important, valuable and illustrated evidence regarding Caesarean section in Arabic literature comes from Al-Bīrūnī who died in 1048 CE at the age of 78 and who was the author of many books on history, medicine and philosophy. One of his unique manuscripts known as Al-Athār al-Bāqiyah `an al-Qurūn al-Khāliyah, is in the University of Edinburgh, MS No. 161. It was edited and translated into German and English by Professor E. Sachau in 1879 [12].

In this chronological history of nations, Al-Bīrūnī gave three references to Caesarean section. He wrote that Caesar Augustus (63 BCE-14CE) was born by post-mortem Caesarean section after his mother died. This is the opposite of the generally mistaken belief that Julius Caesar was born in this manner, as his mother was still alive when he invaded Britain.

|

|

Figure 4: A Page from al-Firdawsī’s Shahnāme showing the Birth of Rustam. A Seventeenth century Persian Manuscript, Wellcome Institute Library, London. |

Al-Bīrūnī also mentioned that Ahmad Ibn Sahl, who was a leader of a revolution against the Sāmānid ruler Nasr II (914-943 CE) of Transaxiana, was born by post-mortem Caesarean section. But the most important and unique evidence is to be found in one of the 24 pictures in this manuscript. This picture gives a clear description of a Caesarean section and is the earliest known book illustration of such an operation (Figure 5). Its importance is even greater when consideration is given to the antiquity of the author.

|

|

Figure 5: Caesarean section as illustrated in the Manuscript of al-Bīrūnī, Al-Athār al-Bāqiyah `an al-Qurūn al-Khāliyah, MS 161, Edinburgh University. |

It seems relevant to mention at this stage that, during the same period, Firdawsī (935-1025 CE) the famous Persian poet, finished his Shāhnāma. In this epic of 60 000 couplets he vividly described Caesarean section. Apart from the colourful and fascinating description of this operation, he also mentioned the use of anaesthesia during the operation [13]. The miniature in Figures 1,2,3 and 4 show a page at Al-Firdawsī’s 17th century manuscript illustrating the well known story of the birth of Rustam. Another unique example of artistic representation of Caesarean section is reproduced in Figure 6, it is dated 1352 by Binyon [14].

|

|

Figure 6: A fourteenth century Persian manuscript, showing the birth of Rustam. Source: L. Binyon, Persian Miniature Paintings, London 1933. |

Many purely religious references have been collected by a German author in a short paper supporting the view that this operation was never prohibited by any well known authority amongst Muslims [15]. The most important reference cited by this author is of Abū Hanīfa (699-767 CE), a highly respected Islamic jurist, who was of the opinion that Caesarean section was allowed on living or dead pregnant women.

In conclusion, it is fair to say that the opinion of some authors that surgery was discouraged and Caesarean section was prohibited by early Muslims was based on unreliable evidence. A search of literature which has already been edited and translated supports the view that early Muslim medical and religious authorities were the first to mention this operation in text and poetry and even to illustrate it in pictures.

[1] “Rique C. Etudes sur la Médicine Légale Ches les Arabes”. GAZ med de Paris 1863; Ser 3: 156-162.

[2] Young JH. Caesarean section. The history and development of the operation from earliest times. London: HK Lewis and Co, 1944.

[3] Wright St Clair RE. “Historical aspect of caesarean section”, NZ Med J 1963; 62: 409-412.

[4] Ullman N. Islamic survey: II. Islamic medicine. Edinburgh: University Press. 1978.

[5] Naqvi NH. “James Barlow (1767-1839): Operator of the first successful caesarean section in England.” Br J obstet Gynaecol 1985; 92: 468-472.

[6] Brügel JE. “Medieval Arab Medicine.” In: Leslie C, ed. Asian medical systems: a comparative study. Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1976: 44-62.

[7] Brown EG. Arabian Medicine, The Fitz Patrick lectures delivered to the College of Physicians. November 1919-November 1920. Connecticut: Hyperion Press Inc. 1983.

[8] Boss J. “The antiquity of Caesarean section with maternal survival, the Jewish Tradition.” Med Hist 1961; 5; 117-130.

[9] Ritter JW. “Post mortem Caesarean section.” JAMA 1961; 175: 715-716.

[10] Said HM. Said HM. Al-Biruni’s book on pharmacy and materia medica. Edited and translated. Karachi: Hamdard National Foundation, 1973.

[11] Spink MS. “Arabian gynaecological, obstetrical and genito-urinary practice. Illustrated from Albucasis.” Proc Roy Soc Med (Section History of Medicine) 1937; XXX: 653-670.

[12] Arnold TW. “The Caesarean section in an Arabic manuscript 707 A.H.” In: Arnold TW, Nicholson RA, eds. A volume of Oriental studies presented to EG Brown. Cambridge: The University Press, 1922: 5-7.

[13] Torpin R. Vafaie I. “The birth of Rustam.” Am J Obstet Gynecol 1961; 81: 185-189.

[14] Binyon L. Wilkinson JVS, Gray B. Persian miniature painting. London: Oxford University Press, 1933.

[15] Haeuber A. “Der Kaiserschmitt im islamischen Kulturkreis.” Geburtsch. U. travenheilk. 1969; 29: 1101-1108.

*FRCA, Consultant Anaesthetist, Bolton General Hospital, Bolton.

4.5 / 5. Votes 155

No votes so far! Be the first to rate this post.

Muslim Heritage:

Send us your e-mail address to be informed about our work.

This Website MuslimHeritage.com is owned by FSTC Ltd and managed by the Foundation for Science, Technology and Civilisation, UK (FSTCUK), a British charity number 1158509.

© Copyright FSTC Ltd 2002-2020. All Rights Reserved.