The Ottoman Mosque Fallacy: Places of Worship Facing the Kaaba or “Monuments of Jihad”?

by David A King

This article is a bio-bibliographical essay on the life and works of Taqī al-Dīn Ibn Ma'ruf, a scholar of 16th-century Istanbul, one of the most prolific and original scientists of the Ottoman period of Islamic science. After a biographical sketch, a comprehensive compilation lists most of his writings from manuscript sources.

by Dr. Salim Ayduz*

Table of contents

3. Astronomical instruments of the observatory

4. Manuscripts of Taqī al-Dīn’s works

4.1. Mathematics

4.2. Astronomy

4.3. Mechanics

|

|

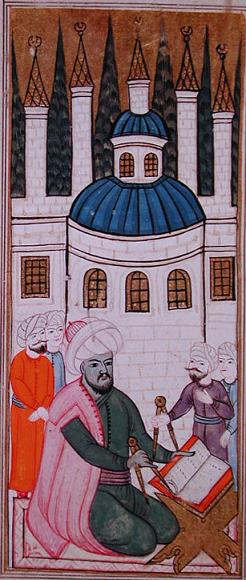

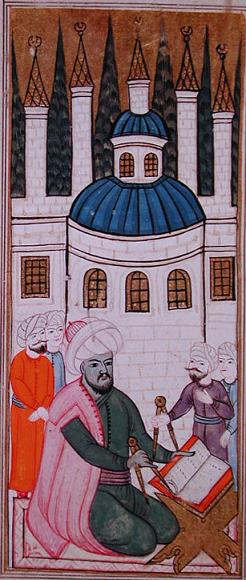

Figure 1: Ottoman astronomers at work around Taqī al-Dīn at the Istanbul Observatory. Source: Istanbul University Library, F 1404, fol. 57a. |

Taqī al-Dīn ibn Ma’rūf was a major Ottoman scientist who excelled in science in the second half of the 16th century. From 1571, he settled in Istanbul, the capital of the Ottoman Empire and excelled in several scientific fields such as mathematics, astronomy, engineering and mechanics, and optics. He was the author of several texts, some of which manuscripts survived and are at present the subject of thorough studies in the history of science. One of his books, Al-Turuq al-saniyya fi al-alat al-ruhaniyya (The Sublime Methods of Spiritual Machines), described the workings of a rudimentary steam engine and steam turbine, predating the more famous discovery of steam power by Giovanni Branca in 1629. Taqī al-Dīn is also known for the invention of a ‘monobloc’ six cylinder pump, for his construction of the Istanbul observatory, and for his astronomical activity there for several glorious years until the observatory was closed.

|

|

Figure 2: Sextant (mushabbaha bi-‘l-manātiq) of Taqī al-Dīn. From Al-Ālāt al-rasadiya li-zīj al-shāhinshāhiyya, Library of the Topkapi Palace Museum, Hazine 452, fol. 14b. |

Taqī al-Dīn Abū Bakr Muhammad ibn Qādhī Ma’rūf ibn Ahmad al-Shāmī al-‘Asadī al-Rāsid (1526-1585), was an Ottoman astronomer originary from Damascus who worked in Istanbul. Known as al-Rāsid (the observer) because of his fame as astronomer and especially as observer and head of the known Istanbul observatory, he excelled also in other scientific branches, from mathematics and optics to mechanics and engineering.

Taqī al-Dīn was born in Damascus in 1526. He worked for a time as a judge and teacher at Nablus (in Palestine), Damascus and Cairo. During his stay in Egypt and Damascus, he produced some important works in the fields of astronomy and mathematics. In 1570, he came to Istanbul from Cairo, and one year later (1571-2) was appointed chief astronomer (Munajjimbashi) upon the death of Chief Astronomer Mustafa b. Ali al-Muwaqqit [1]. Taqī al-Dīn maintained close relations with many important members of the ulema and statesmen, chief among whom was Hoca Sadeddin, and was presented to Sultan Murad by the Grand Vizier Sokullu Mehmed Pasha [2].

|

|

Figure 3: Dhāt al-awtār. From Al-Ālāt al-rasadiya li-zīj al-shāhinshāhiyya, Library of the Topkapi Palace Museum, Hazine 452, fol. 13b. |

Taqī al-Dīn informed Sultan Murād, who had an interest in astronomy and astrology that the Ulug Bey Astronomical Tables contained certain observational errors, resulting in errors in calculations made on the basis of those tables. Taqī al-Dīn indicated that these errors could be corrected if new observations were made and proposed that an observatory be built in Istanbul for that purpose. Sultan Murād was very pleased to be the patron of the first observatory in Istanbul and asked that construction began immediately. He also provided all the financial assistance required for the project. In the meantime, Taqī al-Dīn pursued his studies at the Galata Tower, which he continued in 1577 at the partially completed new observatory that he called Dār al-Rasad al-Jadīd (the New Observatory). He founded the first observatory in Istanbul during the reign of Ottoman Sultan Murad III (1574-1595) which housed a library, comprising mainly books on astronomy and mathematics.

|

|

Figure 4: Observational clock. Source: Ālāt al-rasadiya li-zīj al-shāhinshāhiyya (T), Library of the Topkapi Palace Museum, Hazine 452, fol. 16a. |

The observatory, consisting of two separate buildings, one large and one small, was constructed at a location in the higher part of Tophane in Istanbul. Taqī al-Dīn had the instruments used in the old Islamic observatories reproduced with great care. In addition, he invented some new instruments which were used for observational purposes for the first time. The observatory had a staff of sixteen people-eight “observers” (rāsid), four clerks, and four assistants [3].

The observatory was designed to provide for the needs of the astronomers and included a library and certainly a workshop for the design and the production of instruments. This institution was conceived as one of the largest observatories in the Islamic world and was completed in 1579. It was comparable to Tycho Brahe’s (1546-1601) Uranienborg observatory built in 1576. There is a striking similarity between the instruments of Tycho Brahe and those of Taqī al-Dīn. In his astronomical tables, called the Sidratu Muntaha ‘l-afkār fī malakut al-falak al-dawwār (Culmination of Thoughts in the Kingdom of Rotating Spheres), Taqī al-Dīn states that he started activities on astronomy in Istanbul with 15 assistants in 1573 [4]. The observatory continued to function until 22 January 1580, the date of its destruction. Religious arguments were put forth to justify this action, but it was really rooted in certain political conflicts [5].

3. Astronomical instruments of the observatory

The followings instruments were among those used in the observatory to perform observations:

1) An armillary sphere;

2) A mural quadrant;

3) An azimuthal quadrant;

4) A parallel ruler;

5) A ruler-quadrant or wooden quadrant;

6) An instrument with two holes for the measurement of apparent diameters of heavenly bodies and eclipses;

7) An instrument with chords to determine the equinoxes, invented by Taqī al-Dīn to replace the equinoxial armillary;

8) A mushabbaha bi’l-manātiq, another instrument of his invention, the nature and function of which is not yet explained;

9) A mechanical clock with a train of cogwheels;

10) A sunaydi ruler, apparently a special type of instrument of an auxiliary nature, the function of which was explained by Alauddin al-Mansur.

|

|

Figure 6: Azimuthal semicircle (dhāt al-samt wa’l-irtifā’) of Taqī al-Dīn. Source: Al-Ālāt al-rasadiya li-zīj al-shāhinshāhiyya, Library of the Topkapi Palace Museum, Hazine 452, fol. 452, folio 10a. |

Taqī al-Dīn invented new observational instruments that were added to the array of those already in use for observation in the Islamic world. Among the instruments invented by Taqī al-Dīn in the observatory were the following:

|

|

Figure 7: Parallactic instrument of Taqī al-Dīn. Source: Al-Ālāt al-rasadiya li-zīj al-shāhinshāhiyya, Library of the Topkapi Palace Museum, Hazine 452, fol. 452, folio 11b. |

When we compare the instruments that Taqī al-Dīn used in his observatory with those used by Tycho Brahe, they are mostly similar, but some of Taqī al-Dīn’s are larger and more precise. For example, they both used a mural quadrant (libna) for the observation of the declinations of the sun and the stars. It is said that Taqī al-Dīn preferred a mural quadrant instead of the sudus al-fakhrī and two rings used by the previous astronomers. Taqī al-Dīn’s quadrant was formed of two brass quadrants with a radius of six metres each, placed on a wall and erected on the meridian. The same instrument used by Brahe was only two meters in diameter [9].

|

Figure 8: The quadrant made of rulers of Taqī al-Dīn. Source: Al-Ālāt al-rasadiya li-zīj al-shāhinshāhiyya, Library of the Topkapi Palace Museum, Hazine 452, fol. 452, folio 12b. |

In his observational work, Taqī al-Dīn integrated the Damascus and Samarkand traditions of astronomy. His first task at the observatory was to undertake the corrections of the Ulug Bey Astronomical Tables. He also undertook various observations of eclipses of the sun and the moon. In September 1578, a comet appeared in the skies of Istanbul for one month; the staff of the observatory set to observe it ceaselessly day and night and the results of the observations were presented to the sultan. Taqī al-Dīn was, as a result of the new methods he developed and the equipment he invented, able to approach his observations in an innovative way and produce novel solutions to astronomical problems. He also substituted the use of a decimally based system for a sexagesimal system and prepared trigonometric tables based on decimal fractions. He determined the ecliptic degree as 23º 28′ 40′, which is very close to the current value of 23º 27′. He used a new method in calculating solar parameters. In particular, he determined that the magnitude of the annual movement of the sun’s apogee was 63′. Considering that the value known today is 61′, the method he used appears to have been more precise than that of Copernicus (24 seconds) and Tycho Brahe (45 seconds).

The observatory was witness to a great deal of activity within a short period of time between 1577 and 1580 . Observations undertaken there were collected in a work titled Sidrat Muntahā’l-Afkār fī Malakūt al-Falak al-Dawwār. When compared with those of the contemporary Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe, Taqī al-Dīn’s observations are more precise. Furthermore, some of the instruments that he had in his observatory were of superior quality to Tycho Brahe’s [10].

4. Manuscripts of Taqī al-Dīn’s works

4.1. Mathematics

1. Book on coinciding ratios in algebra (Kitāb al-nisab al-mutashākkala fī ‘l-jabr wa-‘l-muqābala): Cairo (Miqat 557/3, 4 f., Taymur Riyada. 140/10), Oxford (I 88/3). It contains a prologue, three sections and an epilogue.

2. Aim of Pupils in the Science of Arithmetic (Bughyat al-tullāb fī ‘ilm al-hisāb): Cairo (Riyada. 1023), Rome (Vatican Sbath 496/2). It is quoted in Qāmūs al-Riyādhiyyāt of Salih Zeki (vol. II, p. 59) and in The History of Mathematical Literature during the Ottoman Period. It is enclosed also in Al-Hisāb al-hindī, a hand book which contains the book Hisāb al-muanjjimīn wa-‘l-jabr wa al-muqābala (Süleymaniye library, Carullah, MS 1454, 55 folios). The codex had three chapters: 1) on arithmetic with decimal figures, 2) on arithmetic with sexagesimal figures, 3) on algebra.

3. Book on Projecting Spheres onto a Plane (Kitāb tastīh al-ukar) = Preferred Rule in Foundations of Projecting on a Plane (Dastūr al-tarjīh fī qawā’id al-tastīh) – Cairo (Tal’at miqat 135 – anonymous), Istanbul (Kandilli 415/5, 12 folios). It is mentioned under the first title in Kashf al-Zunūn (II 288, III 226). Treatise on stereographic projection; could be part of an astronomical work. The book is dedicated to Hoca Sa’dettin Efendi and has two chapters.

4. Commentary on “Treatise on Classification in Arithmetic” (Sharh risālat al-Tajnīs fī ‘1-hisāb): is mentioned in Kashf al-Zunūn (II 208, III 376). Commentary on the treatise Book on Reduction of the Common Denominator in Arithmetic (Kitāb al-Tajnīs fī ‘1-hisāb) of al-Sakhāwandī.

5. Risāla fī tahqīqi mā qālahu ‘l-‘ālim Giyāthuddin Jamsid fī bayāni ‘l-nisba bayna ‘l-muhīt wa-‘l-qutr (A). Taqī al-Dīn discusses here the ideas of Giyath al-Din Jamshid’s book al-Risalat al-muhitiyya (Istanbul, Kandilli, nr. 208/8, 5 f.).

6. Exposition of “Book on Spheres” of Theodosius (Tahrīr Kitāb al-ukar li-Thawudhūsiyūs): mentioned in Kashf al-Zunūn (I, 390).

4.2. Astronomy

|

|

Figure 10: Taqī al-Dīn and his observatory. Source: Al-Ālāt al-rasadiya li-zīj al-shāhinshāhiyya, Library of the Topkapi Palace Museum, Hazine 452, fol. 452, folio 17a. |

|

Figure 11: The dioptra of Taqī al-Dīn. Source: Al-Ālāt al-rasadiya li-zīj al-shāhinshāhiyya, Library of the Topkapi Palace Museum, Hazine 452, fol. 452, folio 13a. |

7. Fragrance of Spirit on Drawing of Horary [Lines] on Plane Surfaces (Rayhānat al-rūh fī rasm al-sā’āt ‘alā mustawā al-sutūh): Bursa (Haraccioglu 1168/2), Cairo (Falak 3988, Miqat 1140, Fadil Miqat 126, 128, 233, Talat Miqat 182), Istanbul (Suleymaniye Esat 3500, 2033, 2055; Kandilli 132/3, 58, 51; BU Veliyuddin 2305/1; Topkapi Hazine 467/1), Madina (Arif Hikmet 493/2), Oxford (I 881/1, 927), Rome (Vat. 1224), (Kandilli, nr. 123/3, 58 f.); it is quoted in Kashf al-Zunūn (III 524). In addition to those stated above, 5 manuscript copies are mentioned in The History of Astronomical Literature during the Ottoman Period. This book deals with sundials drawn on marble surfaces and their features. It has one prologue and three chapters. It was written in the village of Funduk in Nablus in 1567. This book was commented upon by Taqī al-Dīn’s student Sirāj al-Dīn ‘Umar ibn Muhammad al-Fāriskūrī (d. 1610) under the title Nafh al-fuyūh bi-sharh rayhānat al-rūh; the commentary was translated into Turkish by an unknown writer in the beginning of the 17th century.

8. Non-perforated Pearls and Roll of Reflections (Jarīdat al-durar wa kharīdat al-fikar): Berlin (5699), Cairo (Miqat 900/2, Talat Miqat 76), Istanbul (Kandilli 183, 184; Topkapi Emanet Hazinesi 1711; Suleymaniye Esad Efendi 1976/2), Tehran (Meclis-i Sena 7572/25). It is a small astronomical table for Cairo written in 1581/1582 for Sa’d al-Din Efendi; it contains sine and tangent tables in decimal fractions. The treatise shows Taqī al-Dīn’s scientific abilities and the originality of his contributions. In this work, for the first time we find the use of decimal fractions in trigonometric functions. He also prepared tangent and cotangent tables. According to Taqī al-Dīn, who was the first scholar to succeed in this area, the mathematician Giyāth Jamshīd al-Kāshī (1390 – 1450) tried to solve this problem but failed. (Kandilli, MS 183, 75 folios). Dr. Remzi Demir edited the manuscript as his PhD dissertation [11].

9. Book of Ripe Fruits from Clusters of Universal Instrument (Kitab al-thimār al-yāni’a ‘an qutāf al-āla al-jāmi’a): Cairo (Miqat 557/2), Manchester (361/E), Oxford (I 881/2). It is a commentary on the work “Rays of light on operations wit the universal instrument” (al-Ashi’a al-lāmi’a fī ‘l-‘amal bi-‘l-āla al jāmi’a) of Ibn al-Shātir, describing an astronomical instrument invented by the latter. It is composed of one prologue, thirty chapters and one epilogue (Dar al-kutub, Miqat, MS 557/2, 8 folios).

10. Poem on Sine [Quadrant] (Manzūmat al-mujayyab) – Treatise on Operations with the Transparent Quadrant (Risāla fī’l-‘amal bi-rub’ al-dastūr): Berlin (5834), Cairo (Fadil Miqat 138), Istanbul (Suleymaniye Husnu 135/2, 1 f.), all under the first title. It is a lyric book dealing with the calculations and observations made by the instrument Rub’ al-dastūr. There are two commentaries on the book: one made by Taqī al-Dīn himself and the other by an unknown author (Berlin, MS 5834, 10 folios).

11. Culmination of Thoughts in the Kingdom of Rotating Spheres (Sidrat muntahā al-afkār fī malakūt al-falak al-dawwār (=al-Zīj al- Shāhinshāhī): Istanbul (Kandilli 56, 208/1, 47 folios, NO 2930; Topkapi Hazine 465/1; BU Veliyuddin 2308/2), Rome (Vat. Sbath 496/1). It is quoted in Kashf al-Zunūn (I 394, III 466, 587). Edition of Chapter III (on astronomical instruments): [Sevim Tekeli, “Takiyüddin’in Sidret ül-müntehasinda Aletler Bahsi”, Belleten, Ankara 1961, XXX/98, pp. 228-238]. Turkish translation of the same chapter: Tekeli [ibid] (214-227). These works were prepared according to the results of the observations carried out in Egypt and Istanbul in order to correct and complete Zīj-i Ulugh Beg. In the first 40 pages of the work, Taqī al-Dīn deals with trigonometric calculation. This is followed by discussions of astronomical clocks, heavenly circles, and so forth. Here, he gives information about three eclipses which he observed while he was in Cairo and Istanbul.

12. Book on Knowledge of Position of Horary [lines] (Kitab fi ma’rifat wad’ al-sa’at): Cairo (VI 154); Composed of 10 chapters, it is mentioned in Kashf al-Zunūn.

13. Commentary on His Poem on Conversion of Dates in Different Calendars (Al-Abyāt al-tis’a fī istihrāj al-tawārikh al-mashhūra wa-sharhuhā). Cairo (Fadil Majlis 180/7), Istanbul (Suleymaniye Laleli, 3642/1, 7 f., Lala Ismail 732/6, Hasan Husnu 1135/6; BU Veliyuddin, 2305/6; Topkapi Hazine 467/2). This book contains information about the conversion of calendars from Hijra or to Hijra from other calendars.

14. Knowledge on Reckoning of Lunar Stations (Fī ma’rifat hisāb manāzil al-qamar): Beirut (Safa 22). On the calculation of lunar mansions.

15. Revision of the Almagest: mentioned in Kashf al-Zunūn (V 388).

16. Revision of the Zīj of Ulugh Beg: mentioned in Kashf al-Zunūn (III 197, 490).

17. Treatise on the Azimuth of the Qibla (Risālat samt al-Qibla): mentioned in Kashf al-Zunūn (III 411), it is about finding the direction of the qibla; it has a prologue, one main chapter called a maqsad and fifteen sections.

18. Pearl of the Ordered Simplification of the Calendar (al-Durr (al-‘iqd) al-nazīm fī tashīl al-taqwīm): mentioned in Kashf al-Zunūn (III 197), it is a brief astronomical table on the way to extract the annual calendars through Ulugh Bey Zīj. Cairo (Dar al-Kutub, MS 8008), Oxford (Bodleian, MS 562), Istanbul (Süleymaniye Bagdatli Vehbi, MS 2048/5, 8 folios).

19. Uses on Determining the Equator of the Globe and Knowledge of the Sine (Fawā’id fī istikhrāj mintaqat al-kura wa ma’rifat af-jayb): Cairo (Taymur Riyada 10/13).

20. Simplification of the Shahinshah Zīj (Tashīl zīj al-a’shāriyya al-shāhinshāhiyya): Patna (2466). In this text, Taqī al-Dīn gave the parts of degree of curves and angles in decimal fractions and carried out the calculations accordingly. Excluding the table of fixed stars, all the astronomical tables in this zīj were prepared using decimal fractions.

21. Daqa’iq Ikhtilaf al-Ufuqayn: Cairo (Talat miqat 211/1, 1 f.); about the difference between real and false horizons.

22. The Brightest Stars for the Construction of Mechanical Clocks (Al-Kawākib al-durriyya fi wadh’ al-bankāmat al-dawriyya): Cairo (Miqat 557/1, Sina’a 166/1), Oxford (557), Paris (2478). It was written in 1559 in Nablus and deals with the construction of mechanical clocks and how to use them.

23. Al-Mizwala al-Shimāliyya bi-fadli dā’iri ufuqi al-Qustantīniyya: Oxford (Bodleian, March 119), Istanbul (Kandilli, 547, 13 folios). Taqī al-Dīn wrote this book while he was a judge in Nablus to determine the latitude of Istanbul’s horizon with a kind of round gnomon; it contains one prologue, three chapters and one epilogue.

24. Risāla fī ‘amal āla tursamu bihā al-kawākib ‘alā sathin mustawī: Istanbul (Suleymaniye Yeni Cami 797/3). On the method to draw the map of the sky.

25. Risāla fī al-‘amal bi al-rub’ al-Shakāzī: Cairo (Taymur riyada 169/2, Fihris al-azhariyya VI 303), Edirne (Selimiye 691/3), Garrett (4792), Istanbul (Topkapi III Ahmed 3119/4k, 3 f.), Manchester (361/5). There is no certain proof that this treatise was written by Taqī al-Dīn.

26. Risāla fī ‘l-ikhtilāf bayna al-muwaqqitān bi-mahrusat al-Qāhira fi dabt qawsay al-nahār wa-‘l-layl wa-dā’irat al-fajr wa-‘1-shafaq: Istanbul (Kandilli 208/5, 176, 4 f.), Tehran (Meclis-i Sena 7572/38).

27. Risāla fī ma’rifat al-‘ufuq al-hādith: Istanbul (Kandilli 208/6, 1 f.). It is a notice about the finding of seven horizons.

28. Risāla fī sabab ta’akhkhur ghurūb al-Shams: Istanbul (Kandilli 147, 25 f., 140/3).

29. Risāla fi awqāt al-‘ibādāt. -Istanbul (Kandilli 208/4, 2 f.). It is a treatise that mentions how to use the astrolabes to determination of the time.

30. Tafsīr ba’dh al-ālāt al-rasadiyya: Istanbul (Kandilli 208/2, 2 f.). This text in Turkish mentions eight astronomical instruments that were used by the author in his observatory, with beautiful figures.

31. Urjūza li-‘1-jayb wa-‘1-dharb wa’1-qisma: Istanbul (Uskudar Selim Aga 732m/7, 1 f.; Suleymaniye Huseyin Celebi 748/7, Esad Efendi 3769/10). A poem containing 24 lines on the rules of the Rub’ dā’ira (the quadrant).

32. Preferred Rule in Foundations of Projecting on a Plane (Dastūr al-tarjīh fi qawā’id al-tastīh, titled in some sources as al-Dustur al-rajih li Qawa’id al-Tastih): mentioned in Kashf al-Zunūn (II 288, III 226) and extant in manuscripts at Cairo (Talat miqat 135 – anonymous), Giresun”(155/2), and Istanbul (Kandilli 415/5, 208/3, Arkeoloji Muzesi 601). It is about the projection of a sphere onto a plane as well as other topics in geometry. It is a treatise about the sundials made on the surfaces, written in 1576 and dedicated to Hoca Sa’d al-Din Efendi.

33. [Treatise on the Effect of Refraction at the Horizon and of Differences of Opinions of Cairo Timekeepers Thereon]: Cairo (Talat miqat 11 – only the first page), Istanbul (Kandilli 415).

34. [Treatise on the Difference between True and Visible Horizons]: Istanbul (Kandilli 122).

35. Ālāt al-rasadiya li-zīj al-shāhinshāhiyya (T), Library of the Topkapi Palace Museum, Hazine 452. This book gives the list of astronomical instruments used by Taqī al-Dīn in the Istanbul observatory (Topkapi Sarayi Museum Libr., III. Ahmed, nr. 542, 17 folios). See Sevim Tekeli, “Astronomical Instruments for the Zīj of Emperor,” Arastirma, Ankara 1963, I, pp. 71-121).

36. Jawāb Su’āl ‘an muthallath min al-‘izam gayri qā’im al-zāwiya wa-laysa fī azlā’ihi mā yablugh al-rub’ wa-azlā’uhu bi-asrihā, hal yumkinu ma’rifat zawāyāhu (A). (Süleymaniye Libr., Yeni Cami, nr. 797/2, 1 folio).

37. Fawā’id fī istihrāj mintaqat al-kura wa-ma’rifat al-jayb (A) (Teymuriyye, Riyaza, nr. 140/13, 4 folios).

38. Risālat taqwīm al-sana 990 [H]: on the calendar of the year 990 H. (Süleymaniye Library, Izmirli Hakki, MS 2043/1, 21 folios).

39. Sifat ālāt rasadiya bi-naw’in ākhar (T): Istanbul, Kandilli Library, MS 208/7.

4.3. Mechanics

|

|

Figure 12: Mural quadrant (libna) of Taqī al-Dīn. Source: Al-Ālāt al-rasadiya li-zīj al-shāhinshāhiyya, Library of the Topkapi Palace Museum, Hazine 452, fol. 452, folio 9a. |

40. The Brightest Stars for the Construction of Mechanical Clocks (al-Kawākib al-durriyya fī wadh’ al-bankāmāt al-dawriyya): Cairo (Miqat 557/1, 35 folios, MS Falak 3845, Suway’āt 166/1): it is mentioned in Kasf al-Zunun. With this text, Taqī al-Dīn wrote the first Ottoman book on automatic machines. Composed in 1559 in Nablus. In the foreword, Taqī al-Dīn mentions that he benefited from using Samiz ‘Alī Pasha’s private library and his collection of European mechanical clocks. In this work, Taqī al-Dīn discusses various mechanical clocks from a geometrical–mechanical perspective. Sevim Tekeli, The Clocks in Ottoman Empire in 16th Century and Taqi al Din’s “The Brightest Stars for the Construction of the Mechanical Clocks”. Ankara: T.C. Kültür Bakanligi, 2002.

41. On Science of Clepsydras (Fī ‘ilm al-binkāmāt): Oxford (I 968), Paris (2478).

42. The Sublime Methods in Spiritual Devices (al-Turuq al-saniyya fi’1-alat al-ruhaniyya): Cairo (Falak 3845, Miqat 557/4), Dublin (Beatty 5232), Istanbul Kandilli no 96, autograph). Research: [Tekeli, Sevim, “Taqi Al-Din’s Method in Finding Solar Equations”, ACIHS XI. Sommaires. Varsovie –Cracovie, 1965, 107; Necati Lugal Armagani. 24, 1968, 707-710.], al-Hasan [3]. Treatise in 6 chapters: 1) clepsydras, 2) devices for lifting weights, 3) devices for raising water, 4) fountains and continually playing flutes and kettle-drums, 5) irrigation devices, 6) self-moving spit. In this work, Taqī al-Dīn focuses on the geometrical-mechanical structure of clocks previously examined by the Banū Mūsā and Abū al-‘Izz al-Jazarī. In this book he mentions a six cylinder machine which was invented by him to raise waters, and also some machines for lifting the weights. (Taki al-Din al-handasat al-makaniyyat al-Arabiyya ma’a kitab alt-turup al-saniyya fi al-alat al-ruhāniyya (ed. by A. Yusuf al-Hassan), Aleppo 1987). In 1551, Taqī al-Dīn invented an early steam turbine as a prime mover for a self-rotating spit. Taqī al-Dīn wrote: “Part Six: Making a spit which carries meat over fire so that it will rotate by itself without the power of an animal. This was made by people in several ways, and one of these is to have at the end of the spit a wheel with vanes, and opposite the wheel place a hollow pitcher made of copper with a closed head and full of water. Let the nozzle of the pitcher be opposite the vanes of the wheel. Kindle fire under the pitcher and steam will issue from its nozzle in a restricted form and it will turn the vane wheel. When the pitcher becomes empty of water bring close to it cold water in a basin and let the nozzle of the pitcher dip into the cold water. The heat will cause all the water in the basin to be attracted into the pitcher and the [the steam] will start rotating the vane wheel again.” The History of the literature of natural and applied sciences during the Ottoman Period, (ed. By E. Ihsanoglu and others), Istanbul: IRCICA, 2006, I, 42-44.

43. Risāla fī ‘amal al-mīzan al-tabi’ī (A). It is about weights and measurements and also mentions the scale of Archimedes. (Alexandria, Baladiya [Municipal Library], Majāmi’, MS 3762, 4 folios).

|

|

Figure 13: The colophon of Tarjumān al-atibbā’ wa-lisān al-alibbā’, The National Library of Medicine in Bethesda, Maryland (MS A75, folio 2a) (Source). |

44. Book of the Light of the Pupil of Vision and the Light of the Truth of the Sights (Kitab Nūr hadaqat al-ibsār wa-nūr haqīqat al-anzār): Cairo (Riyada. 893), Istanbul (Kandilli 122, Süleymaniye Libr., Laleli, nr. 2558, 72 folios), Oxford (I 930), Tashkent (446/1). Treatise on optics containing investigations on the vision, the light reflection and refraction in 3 parts. It is dedicated to the Ottoman Sultan Murad III (1574-1595). This book dealt with the structure of light, its diffusion and global refraction, and the relation between light and colour [12].

45. Al-Masābih al-muzhira fī ‘ilm al-bazdara (A). It is about zoology. (Berlin, Gotha, MS 2094, 44 folios).

46. Tarjumān al-atibbā’ wa-lisān al-alibbā’ (The Interpreter of Physicians and the Language of the Wise concerning Simple Medicaments): This is an alphabetical pharmaco-botanical dictionary. Two of manuscript copies of it are known to be extant: MS A75 in 131 folios at the American National Library of Medicine in Bethesda, Maryland, and MS Mq. 527 in the Staatsbibliothek in Berlin (entry no. 6431 in Ahlwardt catalogue).

End Notes

[1] Ihsan Fazlioglu, “Alī al-Muwaqqit: Muslih al-Dīn Mustafā ibn ‘Alī al-Qustantīnī al-Rūmī al-Hanafī al-Muwaqqit”, in Biographical Encyclopaedia of Astronomers, ed. Thomas Hockey, New York: Springer, 2007, I, 33.

[2] J. H. Mordtmann, “Das Observatorium des Taqi ed-din zu Pera,” Der Islam 12 (1913): 93; Ramazan Sesen, “Meshur Osmanli Astronomu Takiyüddin El-Râsid’in Soyu Üzerine,” Erdem 4, no. 10 (1988): 165-171; Cevat Izgi, Osmanli Medreselerinde Ilim, vol. 1 (Istanbul: Iz Yayincilik, 1997): 301-302, 327, 192; Izgi, vol. 2, 128-132; Salim Aydüz, “Takiyüddin Râsid,” Yasamlari ve Yapitlariyla Osmanlilar Ansiklopedisi, vol. 1 (Istanbul: Yapi Kredi Yayinlari, 1999): 603-605.

[3] Ahmet Süheyl Ünver, Istanbul Rasathânesi (Ankara: Türk Tarih Kurumu, 1986), 43-47.

[4] Topkapi Palace Museum Library, MS Hazine 465/1. In addition, see Sevim Tekeli, “Trigonometry in Two Sixteenth Century Works: The De Revolutionibus Orbium Coelestium and the Sidra al-Muntaha”, History of Oriental Astronomy (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987), 209-214.

[5] Sevim Tekeli, “Istanbul Rasathânesinin Araçlari,” Arastirma 11 (1979): 29-44; Sevim Tekeli, “Takiyüddin’de Kiris 2° ve Sin 1° nin Hesabi,” Arastirma 3 (1965): 123-127; Sevim Tekeli, “Takiyüddin’in Delos Problemi ile ilgili Çalismalari,” Arastirma 6 (1968): 1-9; Sevim Tekeli, “Takiyüddin’in Sidret ül-müntehasinda Aletler Bahsi,” Belleten 30, no. 98 (1961): 213-227.

[6] Sevim Tekeli, “Astronomical Instruments for the Zîj of Emperor,” Arastirma 1 (1963): 86-97.

[7] 7. Ibid.

[8] Aydin Sayili, The Observatory in Islam (Ankara: Türk Tarih Kurumu, 1991), 289-305; Aydin Sayili, “Alauddin Mansur’un Istanbul Rasathânesi Hakkindaki Siirleri,” Belleten 20, no. 79 (1956): 414, 466.

[9] Sevim Tekeli, “Meçhul bir yazarin Istanbul Rasathesi Aletlerinin Tasvirini veren: Alat-i Rasadiye li Zic-i Sehinsahiye Adli Eseri,” Arastirma 1 (1963): 12-71.

[10] Sevim Tekeli, “Nasiruddin, Takiyüddin ve Tycho Brahe’nin Rasat Aletlerinin Mukayesesi,” Ankara Üniversitesi, Dil ve Tarih Cografya Fakültesi Dergisi 16, no. 3-4 (1958), 224-259.

[11] Takiyüddin’in Cerîdet el-Durer ve Harîdet el-Fiker Adli Eseri ve Ondalik Kesirleri Astronomi ve Trigonometriye Uygulamasi, Ankara University, DTC Faculty, Philosophy Department, 1991.

[12] Studied in Topdemir, Hüseyin Gazi, “Taqī al-Dīn’s Optics Book Named The Nature of Light and The Formation of The Vision”, Doctoral Dissertation, Advisor: Prof. Dr. Sevim Tekeli. Ankara Üniversitesi Dil ve Tarih-Cografya Fakültesi, xii+816 pages.

* Senior Researcher at the Foundation for Science, Technology and Civilisation, UK and Research Visitor at the School of Languages, Linguistics and Cultures, The University of Manchester, UK.

4 / 5. Votes 165

No votes so far! Be the first to rate this post.

Muslim Heritage:

Send us your e-mail address to be informed about our work.

This Website MuslimHeritage.com is owned by FSTC Ltd and managed by the Foundation for Science, Technology and Civilisation, UK (FSTCUK), a British charity number 1158509.

© Copyright FSTC Ltd 2002-2020. All Rights Reserved.