This article discusses the view that the simurgh, a mythological bird with supernatural characteristics, was also a symbol of miraculous life and treatment, as related in stories and miniature pictures. Such as view is described specifically with examples of Turkish miniatures.

This article was first published as: Nil Sari, “The Simurgh: A Symbol af Holistic Medicine in the Middle Eastern Culture in History”, Proceedings of the 37th International Congress of the History of Medicine (September l0-l5, 2000 Galveston Texas, USA). Galveston, Texas, 2000: l56-158. We are grateful to Professor Nil Sari for allowing publication.

* * *

Belief in a divine healing energy from higher metaphysical planes into the physical body, that is, the religious interpretation of the holistic healing process, had its symbolic myths in history. Man, throughout history, feeling helpless against the difficulties he came across, and being unable to reach the Creator, hoped for imaginary help from supernatural creatures, whether they are represented by God, a human being or an animal. These imaginary and strange creatures, designed with different organs of animals, appeared within the frame of social beliefs and ideas, used in literature and works of art as a means to describe the supernatural. Referring to fantastic creatures that over rule his destiny, the human being gave meaning to some of them as symbols of medicine such as immortality, miraculous treatment, revival and rebirth, etc. One of these fantastic creatures is the simurgh, which was imagined to be a huge bird of prey, which did not exist, yet had a name. It was believed that those who obtained the feather of this bird could reach the greatest secret of the universe and immortality.

In this paper, the view that the simurgh, a mythological bird with supernatural characteristics, which was also a symbol of miraculous life and treatment, as related in stories and miniature pictures, is described specifically with examples of Turkish miniatures.

|

|

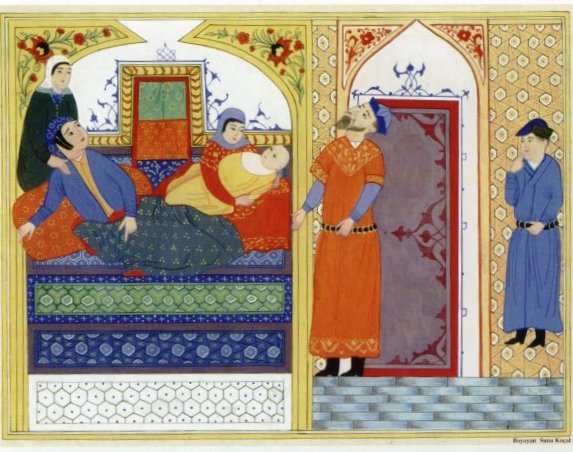

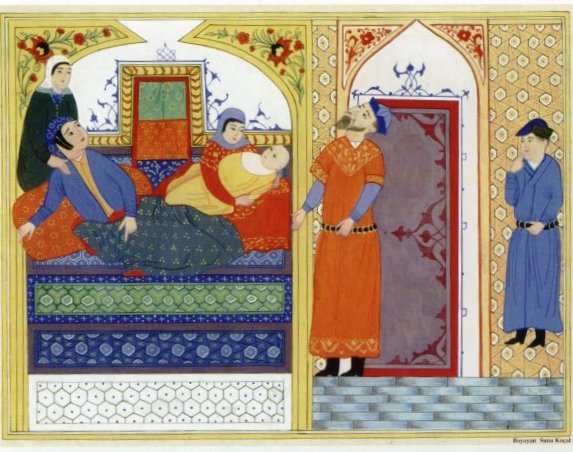

Figure 2: Rustam’s birth: Shahnamah Firdaws (Book of Kings of Firdaws, at the Topkapi Palace Museum Library, H. 1520, fol. 72b.). © Nil Sari and Ulker Erke. |

The simurgh varies in different cultures in the Middle East. Though the simurgh concept is generally known to be Persian in origin, the mythology related with it goes far back in history. According to the Persian mythology, the simurgh lived on the imaginary Qaf of Elburz Mountain, on the top of the Gaokerena tree, which contained the seeds of the elixir of immortality. This feature resembles the Indian mythology of the Garuda bird. Similarities with several other features related with the simurgh concept are also found in the ancient Chinese, Egyptian, and Greek mythologies.

Mythological birds existing from the pre-Islamic Turkish culture period survived in the memory of the society, preserving its symbolic expression, reappearing again and again in Turkish literature and art. In Central Asian and Middle Eastern mythologies, the motif of the black bird or the eagle and the life tree on which it perched, the influence by the Indian mythological Garuda through Buddhism and Manichaeism, and the symbols related with the simurgh called Zumrut-u Anka by the Arabs and Muslim Turks, continued the relation established with the supernatural and survived as a totemic archetype in the Seljuk and Ottoman Turkish cultures. The simurgh, which comes forth as an important symbol in art and literature, is described and illustrated in two ways in the Turkish-Islamic culture. One is a symbol of goodness and is equivalent to the idea of the good spirit in the pre-Islamic Turkish faith, and this is the bird we are going to present. The other one is a symbol of evil. The pre-Islamic Turkish art, affected by Chinese and Indian art illustrating animals, was merged with and came to be used in a similar sense with the simurgh of the Anatolian Turks.

|

|

Figure 3: Hippocrates on the simurg on his way to prepare drugs (Falname, Topkapi Palace Museum Library, H. 1703, fol. 38b). © Nil Sari and Ulker Erke. |

The eagle or the birds of prey that perch on the top of the sacred beech tree were symbols of the God of Heaven in the pre-Islamic Turkish culture. For instance, the two-headed bird named Semurk by the Baskurd Turks, was also believed to live on the peak of the mountain Qaf, like the simurgh.

In the Er-Tostuk’s tale of the Turkish mythology, the dragon named acirga was the guard under the life tree on which the bird perched, and in a part of the epic, Er-Toshtuk kills the dragon which ate the young of the black bird. The birds’ mother swallows Er-Toshtuk by the side of the tree but, when she learns the truth from her young, she spits him out and creates a young man by means of the life energy supplied from the life tree. Er-Toshtuk rides on the bird’s back and asks her to take him down to the earth. They start flying towards their destination, though the food of the bird gets consumed midway. Er-Toshtuk lends his own meat and eye to the bird to eat. When they reach earth, the bird swallowing and then spitting him out again, revives him as a young man. As in this tale, the simurgh is illustrated fighting the dragon which ate her young. This theme is dealt with in Palace albums, specifically in the Yakub Bey albums of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries Timurid and Turcoman periods following the style called saz (meaning rush), along with woods features.

|

|

Figure 4: Rustam’s birth: Shahnamah Firdaws (Book of Kings of Firdaws, Topkapi Palace Museum Library, H. 1496, fol. 60a.). © Nil Sari and Ulker Erke. |

Some famous personalities of the ancient and Islamic periods are also reflected in Ottoman Turkish art and literature in relation with the simurgh. For example, in an illustration in a seventeenth-century large-sized fortune book called Falname, written in Turkish for the use of fortune-tellers, Hippocrates is illustrated dressed in a contemporary Ottoman costume, depicted on his way to the mountain Qaf to prepare medicine. It is a variety of the same myth.

Another interesting example is Hazret-i Hamza, the Prophet’s uncle who was illustrated on the simurgh on his way to the mountain Qaf. As his life was a very popular story narrated by Turkish storytellers in the Ottoman period, this illustration was used for recitation of the story. The stories about the life of Hamza and his fights to further Islam gained a fantastic characteristic of adventure, full of miraculous events through history.

Remarkable miniatures of the simurgh with regard to medical history are found in Shahnamah (Book of Kings), the most famous epic of the Middle East, compiled by Firdawsi in the years 990 and 1001 during the reign of the Turkish khan Mahmud of Ghazna. However, the content of Shahnamah does not only go further back in Persian history, but researchers have discovered that there are similar tales in Chinese mythology existing before the ancient Persian stories. Shahnamah came to be one of the most famous epics in the Middle East countries and it started to be told and translated into various languages at the end of the tenth century when it began to be written.

|

|

Figure 5: The birth of the calf named Purmaye. Image from Shahnamah Firdaws (Book of Kings of Firdaws), Türk Islam Eserleri Müzesi Kütüphanesi, 1978, fol. 15b). © Nil Sari and Ulker Erke. |

Telling and listening to tales during long winter nights was an important tradition in the East. As there were no media such as the press and television, the artists illustrated the stories in accordance with their artistic traditions and style of their time, and the imaginative capacity of the artist was of great importance, as well as his ability as an artist.

Shahnamah is a work dealing with fantastic mythological creatures. One of the creatures that has supernatural characteristics is the simurgh. According to the well-known story, a son was born to Sam, a hero of the epic. His nurse announced the birth of the son saying his skin is as pretty as silver and his cheeks as beautiful as paradise; not any ugly spot could be found in his body. This baby’s only misfortune is his white hair. Hearing these words, Sam went to his wife. There he saw a child with an aged-looking head. Until then he had neither seen, nor heard of such a child. All the hair on his body was white. Only his cheeks were red and a little odd. After having seen his child’s hair like this -pure white in colour- he was disappointed, and regarded this case as God’s punishment because he had averted from the route of wisdom and maturity. Being very sad and feeling disgraced, he thought that all the great men of the world would laugh at him secretly or openly and ordered the child to be taken away from the country. There was a mountain named Elburz, near the sun and far away from human beings. The simurgh’s nest was there, for he kept his nest away from man. They abandoned the child there and came back. Having heard the crying of the child, the simurgh was inspired with a deep feeling of love and mercy and so it protected and took care of him and brought him up. One night years later, his son Zal was seen to Sam in his dream, so he decided to look for his son and went to the simurgh’s nest. Seeing the child’s father coming, the simurgh comforted Zal and flew up into the sky with Zal on his back and then dived down promptly to take him to his father. The simurgh gave three feathers from its wings to Zal to use for help in case of danger. This is the well-known story of Zal, one of the most famous examples in history of the exposure and abandonment of defective or malformed infants to death. Its illustrations are probably the earliest examples of an albino in genetic history. Art historians assume that most of the simurgh illustrations in Turkish miniature art, examples of which are presented in this study, were inspirations from Garuda illustrations in the Indian mythology. The scene depicting the simurgh with the child on his back is one of the similarities.

|

|

Figure 6: Newly born albino Zal. Image from Shahnamah Firdaws (Book of Kings of Firdaws), Türk Islam Eserleri Müzesi Kütüphanesi, 1978, fol. 41a). © Nil Sari and Ulker Erke. |

The use of the simurgh symbol for miraculous treatment is told in connection with the famous story of Rustam‘s birth in the Shahnama. As the story goes, when time comes for Rudaba to give birth to Zal‘s child, she fails. She feels as if her skin was filled up with stone or that the creature in her womb was made of iron. At last one day, she becomes completely unconscious. Consequently, there arise cries from the palace of Zal. Women in the Harem pull off their hair and tear their turbans open, wet their faces and hair with their tears. Then Zal recalls the wing of the simurgh and bums a small piece of it. On this, the sky darkens suddenly and the bird reigning over the world comes down like a cloud and asks Zal, “Why do you look so sad? What do tears have to do in the eyes of a lion?'” The simurgh informs him of the birth of his brave son: “Bring me a dagger made of steel and bring a highly intuitive wise man. First of all get the moon-faced Rudaba drunk with wine and free her from the fear and anxiety in her heart. You must see that. The wise man you call will deliver the child miraculously from the womb of Rudaba. He is to open the womb without giving her any pain, deliver the child and then stitch the highly bleeding cut. Don’t fear and free your heart from all anxiety. Get the plant I am going to tell you now, pound it with milk and musk, and having dried them all in the shade, apply them to the wound. You will see that, after this treatment the patient will stop feeling any pain. Then, when you rub my feather on it you will see the influence of my power.” Zal carried out the simurgh’s directions immediately.

|

|

Figure 7: Zal, the albino, on the simurg. Shahnamah Firdaws (Book of Kings of Firdaws), Topkapi Palace Museum Library, Album No 2153, vr. 23a). © Nil Sari and Ulker Erke. |

Finally, a wise man with skilful hands came and first got the moon-faced Rudaba drunk with wine. Then, he incised the womb of that moon-faced woman and taking the head of the baby away from its natural route, got it out without giving it any harm in such a way that no one had ever seen before an astonishing practice like this. Nobody remembered any child to have been born with hands covered with blood like this. His drunken mother slept day and night. Wine had caused her to fall into deep sleep. Soon they stitched her wound and applied medicine on it. They named him Rustam, meaning “‘it got saved.” As far as we know, the earliest Islamic illustrations of birth by means of Cesarean section are those that illustrate this story, not excepting the illustration of the birth of Caesar in a manuscript copied in 1307, of a history by Biruni. The beautiful fourteenth, fifteenth, and sixteenth century miniature pictures depicting this legend of the miraculous birth realized by the help of the simurgh are found in the Shahnamah copies written in Persian and Turkish, kept in the Topkapi Palace Museum and Turkish-Muslim Works Museum libraries.

The efforts of the simurgh to keep Rustam alive were not yet to be completed, for when Rustam and his horse named Rakhsh got wounded in the fighting with Isfendiyar (a mythological hero, slain by Rustam), they were treated by the simurgh, as depicted in an illustration on the lines of the fifteenth century (1460) Timurid art style. This single page Shahnamah illustration on a large sheet of paper, found in a palace album, was also used for the traditional recitation of stories.

|

|

Figure 8: The petition room (arz odasi) of the Ottoman Sultans living in the Topkapi Palace. (© Salim Aydüz). |

In Seljukian and Ottoman Turkish art, like other figures existing before Islam, the simurgh continued to represent the abstract thought, but in the context of Islamic mysticism, it will represent the power in belief looked for by the Muslim individual. As the Muslim artist averted gradually from drawing figures of the pre-Islamic period, in the course of time the simurgh continued to live among stylized plant illustrations as a figure changed through the years.

On the other hand, after Islam, the simurgh is found as a symbol of sufism (tasawwuf-Muslim mysticism) in literature, where oneness in existence (Vahdet-i Vucud), that is the idea that there is only one existence in the cosmos, is treated. The only being is God, the Creator. Everything that is seen are his various reflections. “God’s essence is diffused throughout the world.” The Creator is manifested continuously in different forms; therefore, everything seems to be real. Attar and his followers treat this basic idea, represented by the simurgh, for the simurgh is a symbol of God’s manifestation. According to the story, the simurgh is nothing but all of the birds. But in order to be able to comprehend this, the birds must pass some stages through the travel of the Soul. The travel, that is the spiritual evolution, is described by means of myths, symbols, and allegories related with the simurgh.

Thus, while ideas about the mythological bird simurgh living behind the imaginary mountain Qaf came to be a symbol for Sufism, skilled artists went on decorating their work using designs related with the simurgh. Until the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the motif of the simurgh – the emperor of feathered birds- came to symbolize the meaning of the forest in the miniature pictures in the rush style and continued to be illustrated in Ottoman art, depicting the fight between the simurgh and the dragon. And, Huma, a fantastic bird in Turkish mythology, a symbol of prosperity and good luck (devlet kusu), intermingling with the simurgh (Zumrut-u Anka) concept, took its place in the dome of the petition room (arz odasi) of the Ottoman Sultans living in the Topkapi Palace.

* Head of the Medical Ethics and History Department, Istanbul University, Cerrahpasa Medical School.

4.9 / 5. Votes 171

No votes so far! Be the first to rate this post.

Muslim Heritage:

Send us your e-mail address to be informed about our work.

This Website MuslimHeritage.com is owned by FSTC Ltd and managed by the Foundation for Science, Technology and Civilisation, UK (FSTCUK), a British charity number 1158509.

© Copyright FSTC Ltd 2002-2020. All Rights Reserved.