Lunar Formations and Astronomers from Muslim Civilisation

by Salim Al-Hassani - 1001 Book Chief Editor

Book Review of “Reflections on Observational Astronomy in the Medieval Islamic Period” by S. Mohammad Mozaffari

by Fatima Sharif

Did Copernicus borrow his cosmological theory from an earlier Muslim scientist? New research reveals that the cosmological model developed by Nicolaus Copernicus, the renowned European Renaissance polymath, closely resembles one designed by an Arab astronomer nearly two centuries earlier.

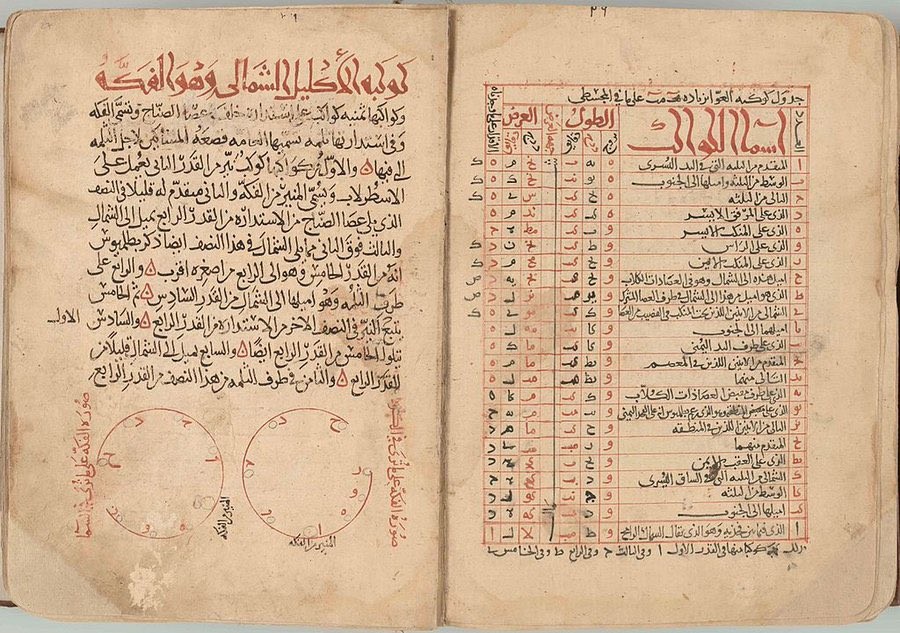

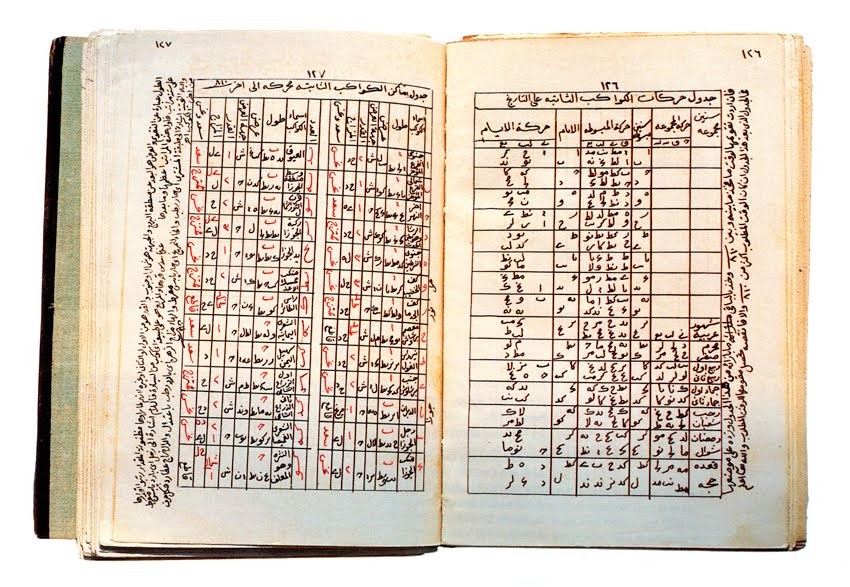

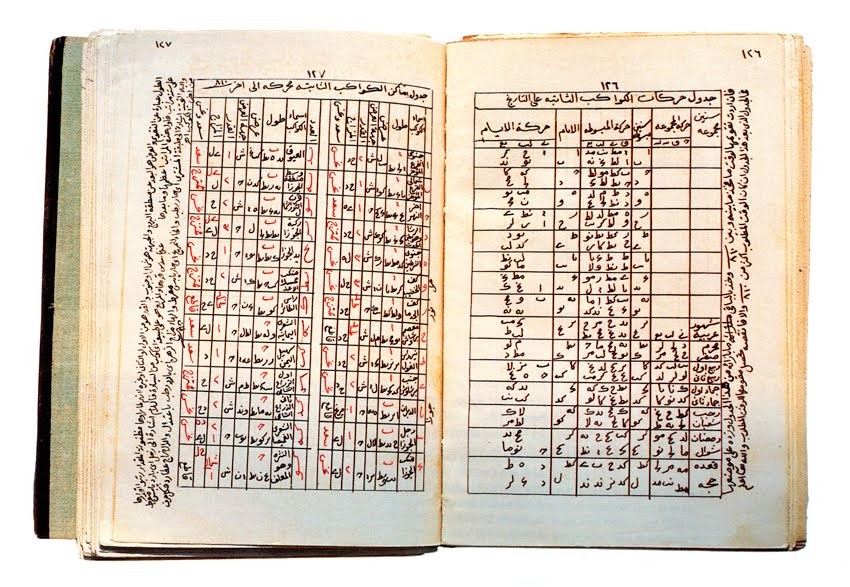

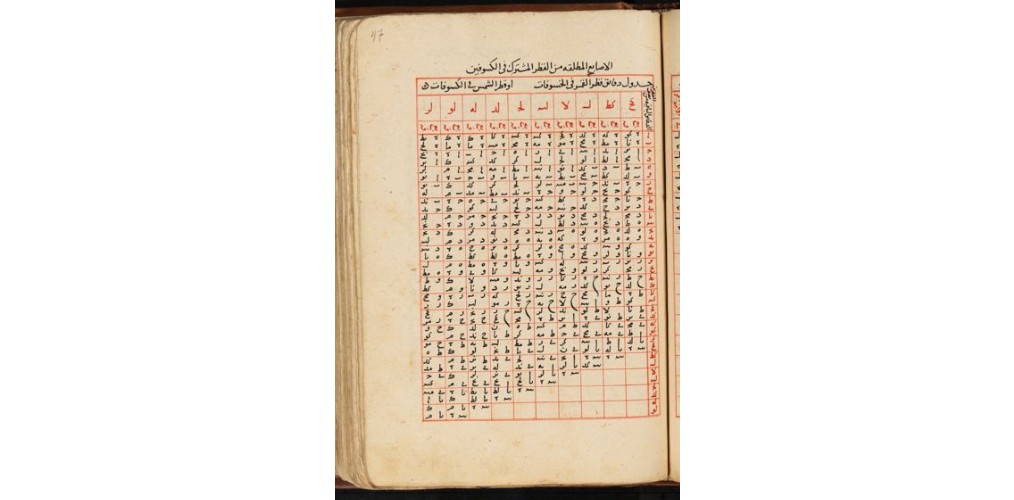

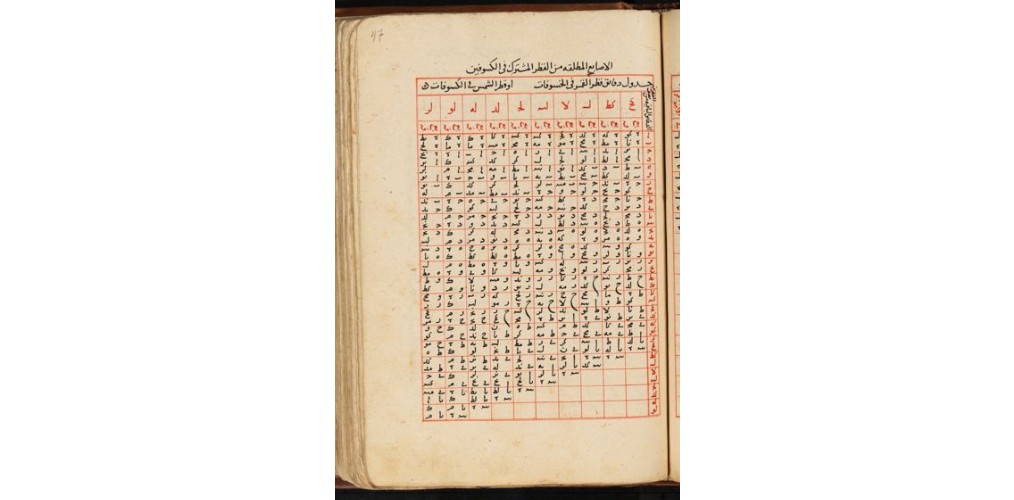

Figure 1. Star names – Table of geographical longitude and latitude in (a later reworking of) the astronomical handbook of Ulugh Beg, reputed as the legendary Islamic astronomer. Credit: Leiden University Libraries.

***

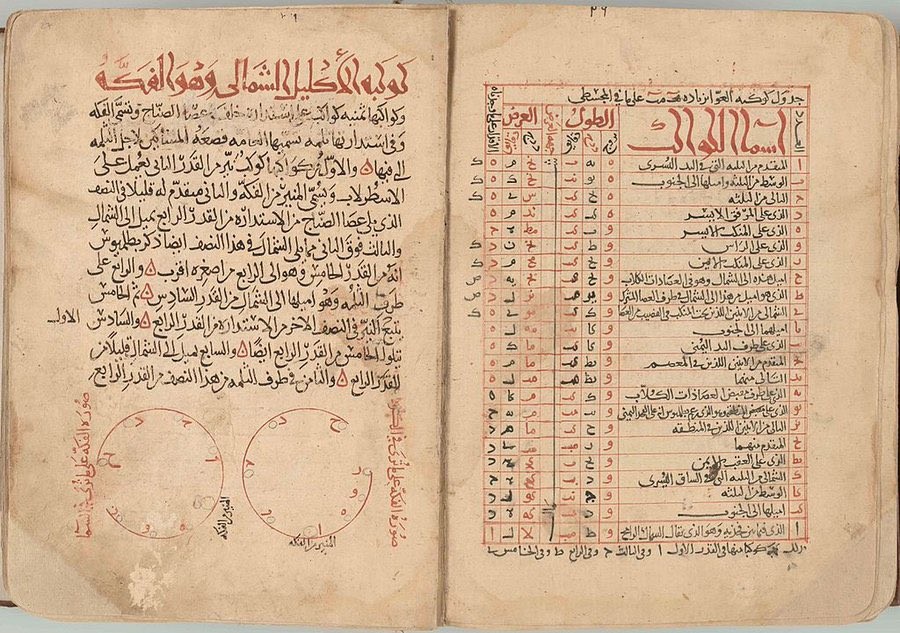

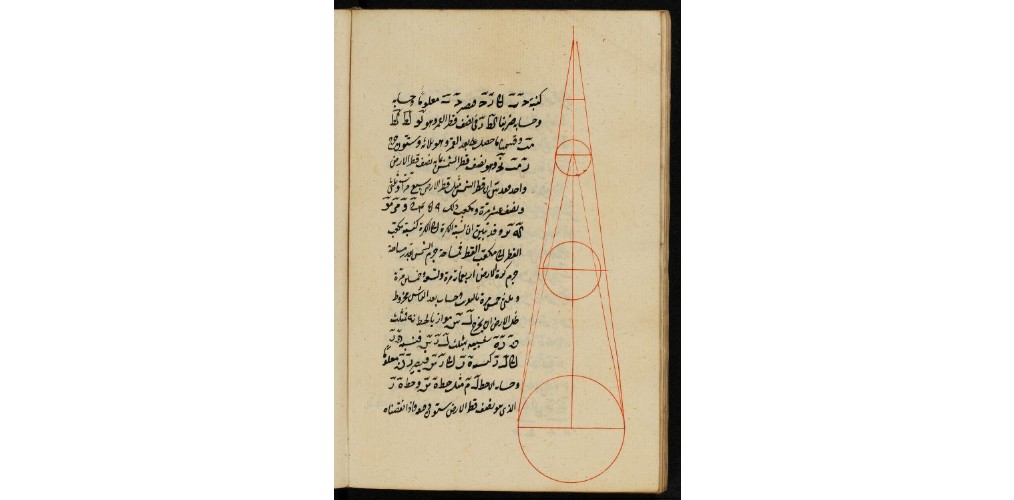

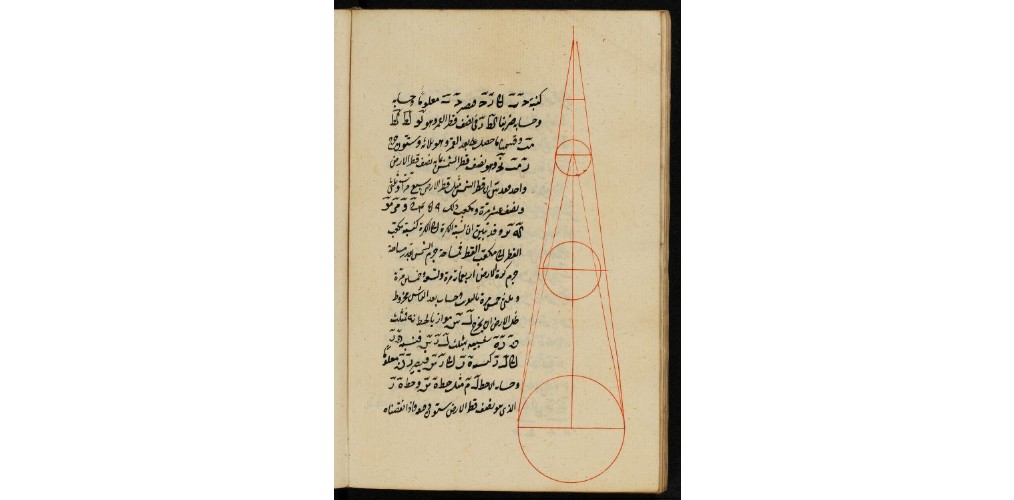

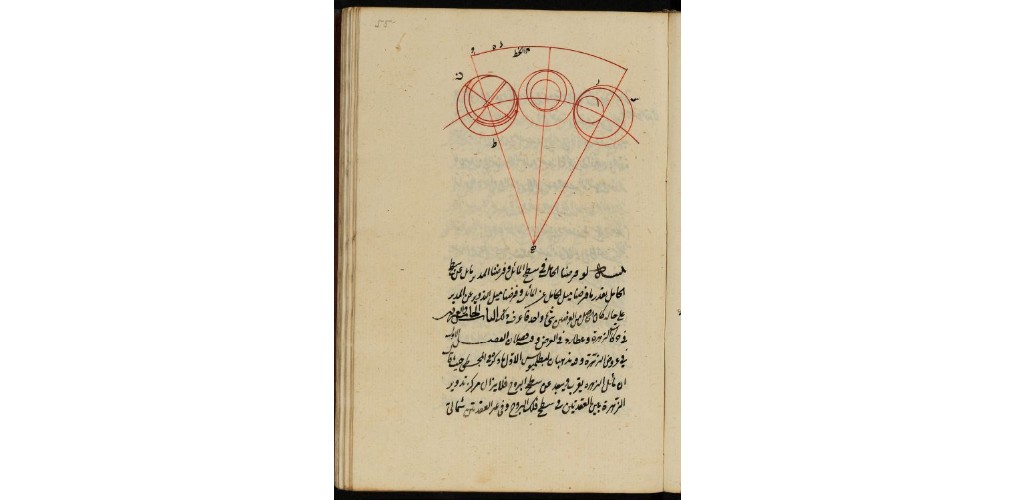

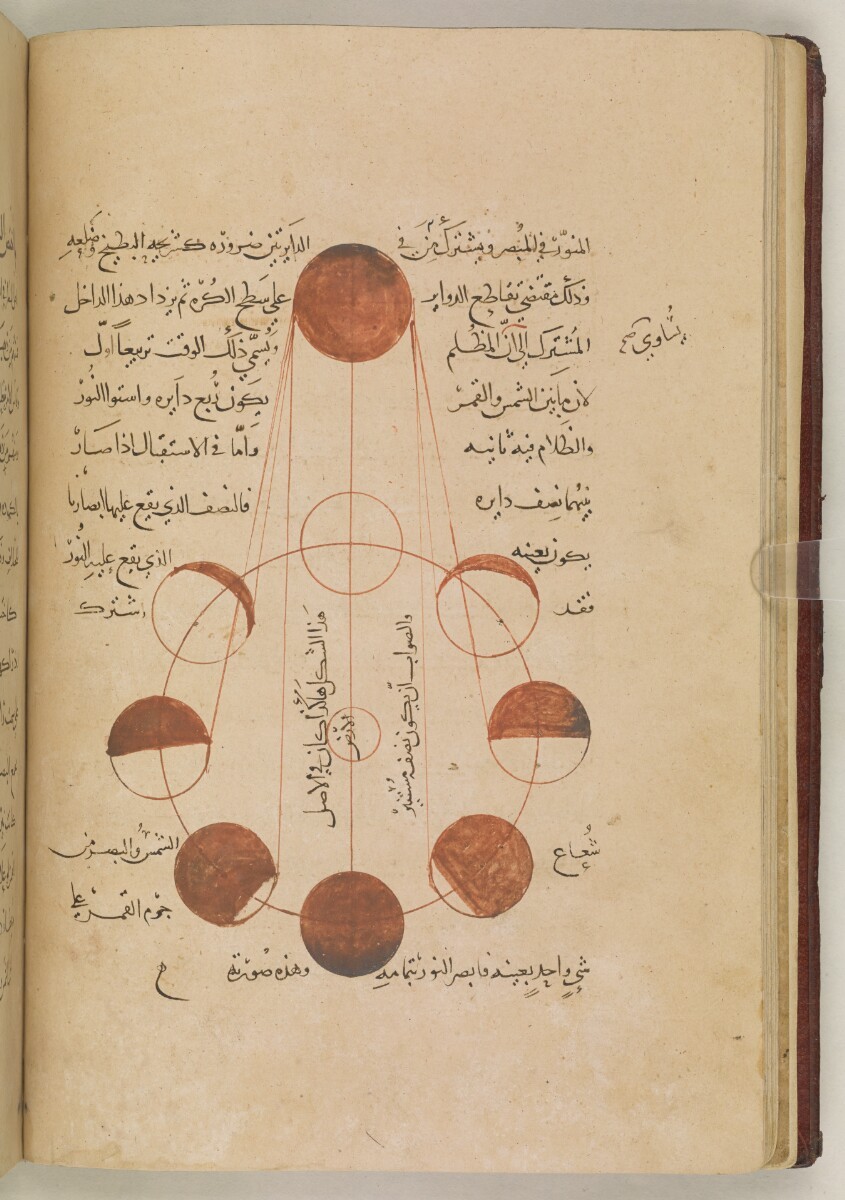

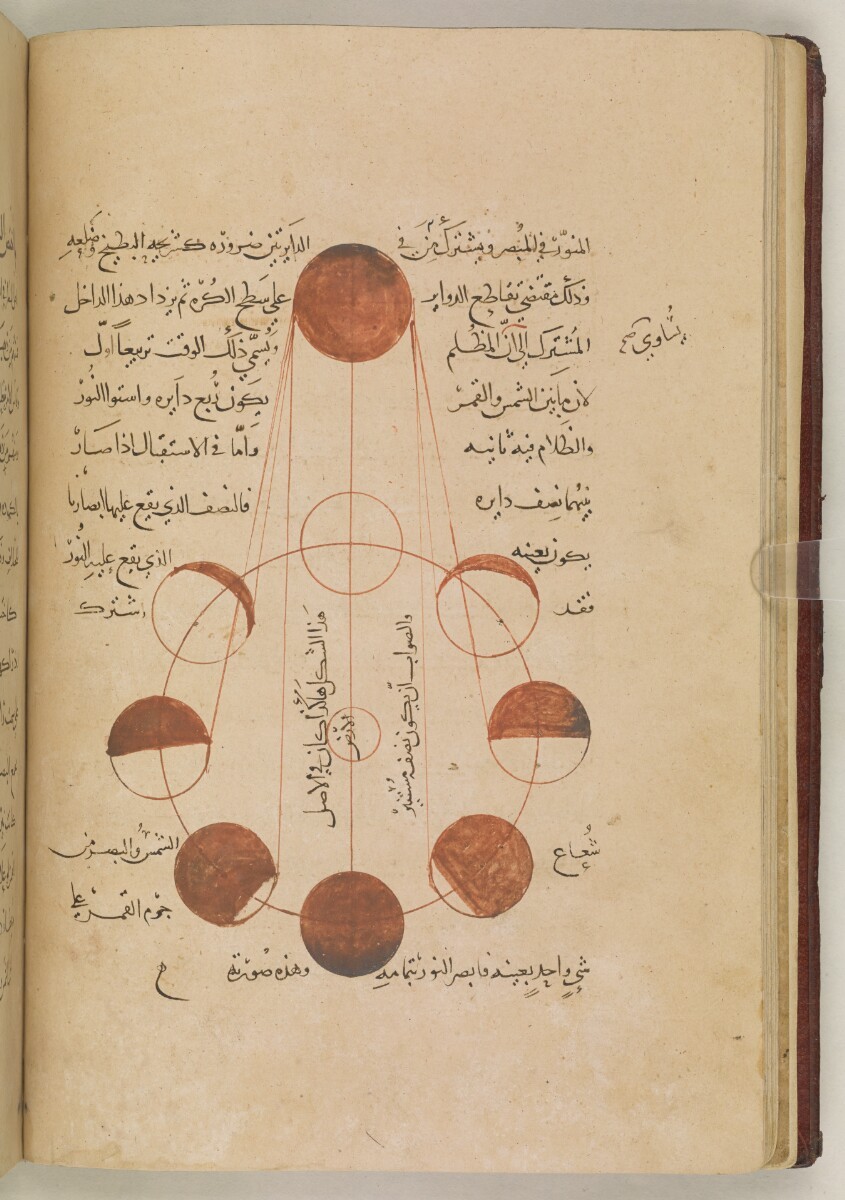

Figure 2. Ancient lunar model – Ibn al-Shatir’s lunar model from which Copernicus is reported to have borrowed in composing his cosmological model. Credit: This work is in the public domain in the United States. (Source)

Copernicus, a Polish astronomer who lived in the 16th century, is believed to be one of early European scientists to put forward the theoretical model that the Sun was the center of the solar system, defying both the church and prevailing intellectual paradigm of his time, which held that the Earth was the center of the universe.

Copernicus’s model is called sun-centered or heliocentric. In it, he challenges centuries-old scientific beliefs based on the teachings of Aristotle and Ptolemy, who held that the Earth was at rest at the center of the universe with other planets, including the sun, orbiting around it.

The research conducted at the University of Sharjah is a comparative and analytical study which examines the writings of Copernicus in parallel with the works of the 14th-century Muslim astronomer Ibn al-Shatir.

A recently completed Ph.D. thesis posted to the Sharjah University Library website, the research textually and critically analyzes the contributions of the two scientists to identify where they concur or diverge in presenting their theories, despite a historical gap of more than 200 years between them.

Dr. Salama Al-Mansouri, the author of the thesis, places Ibn al-Shatir’s cosmological model at the forefront of astronomical achievements in the Islamic scientific tradition. Dr. Al-Mansouri says:

“Ibn al-Shatir was the first astronomer to have successfully challenged the Ptolemaic cosmological system of planets revolving around Earth and corrected the theory’s inaccuracies about two centuries before Copernicus,”

The fact that Copernicus drew from the works of earlier scientists and astronomers is not new. However, the study highlights the significant similarities between Copernicus and Ibn al-Shatir, an engineer, mathematician, and astronomer who was the timekeeper for the Umayyad Mosque in Damascus, Syria.

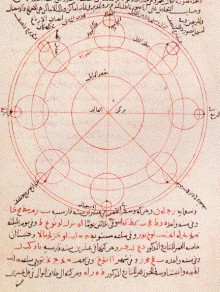

Figure 3. A manuscript of Ibn al-Shatir (in Arabic) with tables showing movements of stars per years, months, and days. Credit: The Leiden University Libraries.

By correlating the two cosmological models, the study suggests Copernicus was heavily influenced by Ibn al-Shatir’s astronomy and his ideas that the Earth and other solar planets orbit the Sun. Mesut Idriz, professor of history and Islamic civilization at the University of Sharjah and one of the study’s supervisors, says:

“Ibn al-Shatir’s astronomical manuscripts, particularly his work in Nihāyat al-Sul, demonstrate planetary models that predate and closely mirror those later proposed by Copernicus, indicating a shared mathematical lineage,”

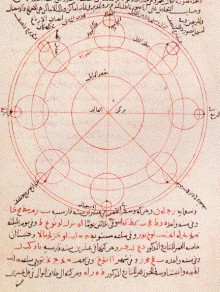

Nihayat al-sul fi tashih al-usul, or ‘The Final Quest Concerning the Rectification of Principles’, is Ibn al-Shatir’s most influential and important astronomical treatise in which, according to the study, the Muslim scientist corrects and refines many of the Ptolemaic models of the Sun, Moon, and planets.

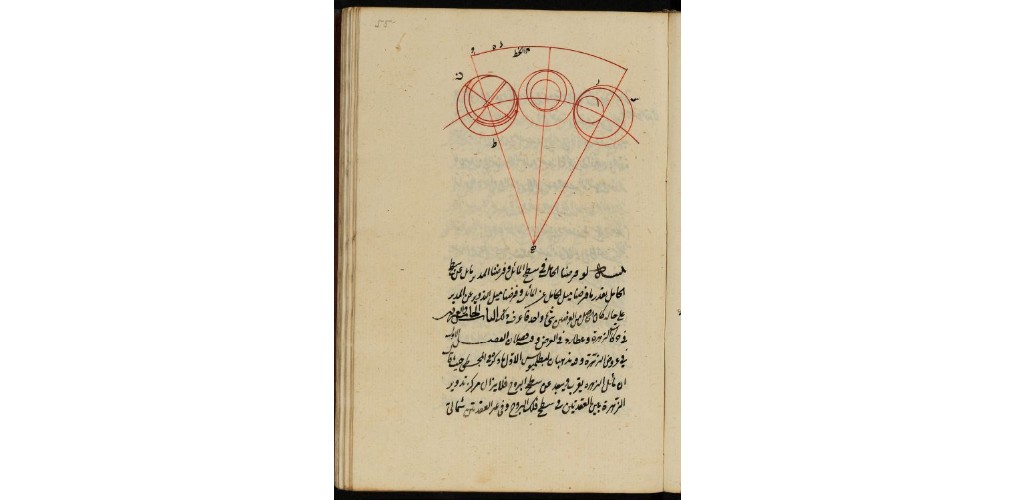

Figure 4. Rectifying ancient Greek theories – A page from Nihayat al-sul fi tashih al-usul, or ‘The Final Quest Concerning the Rectification of Principles’, which was Ibn al-Shatir’s most influential and important astronomical treatise. Credit: The Leiden University Libraries.

Prof. Idriz acknowledges the complexity of studies based on “historical astronomical manuscripts” as they need to combine:

“…unique intersection of expertise—astronomy, manuscript studies, and historiography. Muslim manuscript-based research is an intricate process that requires fluency in Arabic and Persian, the medium of writing for Muslim scientists.”

Interpreting medieval astronomical manuscripts is no easy task as it demands methodological precision, tracing textual transmission, comparing mathematical formulations, and evaluating observational data. To surmount such a sophisticated multidisciplinary approach, Dr. Salama sought advice and assistance from the community of academics at the Sharjah Academy for Astronomy, Space Sciences and Technology (SAASST), which has become a hub for renowned Arab and Muslim astronomers and scientists.

Dr. Salama conducted a critical textual analysis between Copernicus’s most famous work, De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (‘On the Revolutions of the Celestial Spheres’) – a landmark in the history of science, which triggered the so-called Copernican Revolution – and the astronomical manuscripts of Ibn al-Shatir, particularly his Nihayat al-sul fi tashih al-usul.

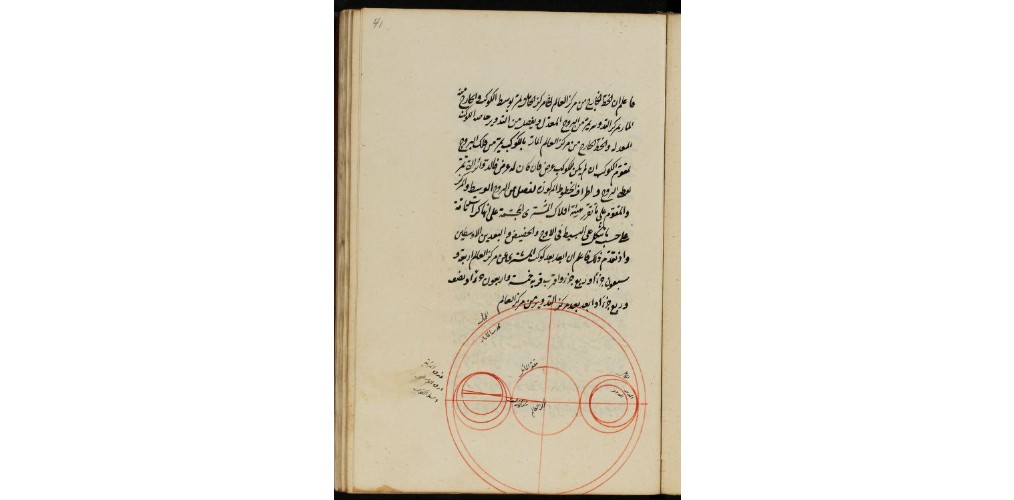

Figure 5. Cosmological model – An extract from Ibn al-Shatir’s Nihayat al-sul fi tashih al-usul, or ‘The Final Quest Concerning the Rectification of Principles’, in which he expounds his cosmological model. Credit: The Leiden University Libraries.

The study reveals compelling correlations, underscoring the pivotal role of manuscript translation and transmission in the evolution of heliocentric theory, while also assessing how unravelling Muslim manuscripts can rectify historical inaccuracies about the history of science.

On the importance of the correlations between the work of Copernicus and that of Ibn al-Shatir, Mashhoor Al-Wardat, professor of astrophysics at SAASST, says:

“The striking similarity between the planetary models developed by Ibn al-Shatir and Copernicus, particularly those concerning the orbits of Mercury and the Moon, provides clear evidence of Copernicus’s reliance on Ibn al-Shatir’s work …This raises profound questions about the transmission of knowledge from Islamic civilization to Europe and about the roots of modern astronomy.”

Dr. Salama provides an overview of Arabic manuscripts and their Latin translations in European archives in Kraków in Poland and the Vatican, where Copernicus made his most outstanding contribution to astronomy. She finds that Ibn al-Shatir’s treatise Nihayat al-sul fi tashih al-usul was among the archives. She goes on:

“Though in its original Arabic version, the manuscript could not have escaped the attention of a scholar like Copernicus.”

The study provides no definitive proof that Copernicus had read Ibn al-Shatir’s works, as there were no Latin translations of Ibn al-Shatir’s writings accessible to the researcher. However, the research posits that the Polish astronomer most probably had access to Ibn al-Shatir’s ideas through “intermediary channels”, given the strong resemblance between their interpretations and mathematical calculations of planets orbiting the Sun.

The textual parallels between the two astronomers, according to the study, are most noticeable in “the identical calculations and results … imply(ing) that Copernicus may have adapted Ibn al-Shatir’s techniques” in developing “his philosophical shift to heliocentrism”, a model which the study admits was Copernicus’s own invention.

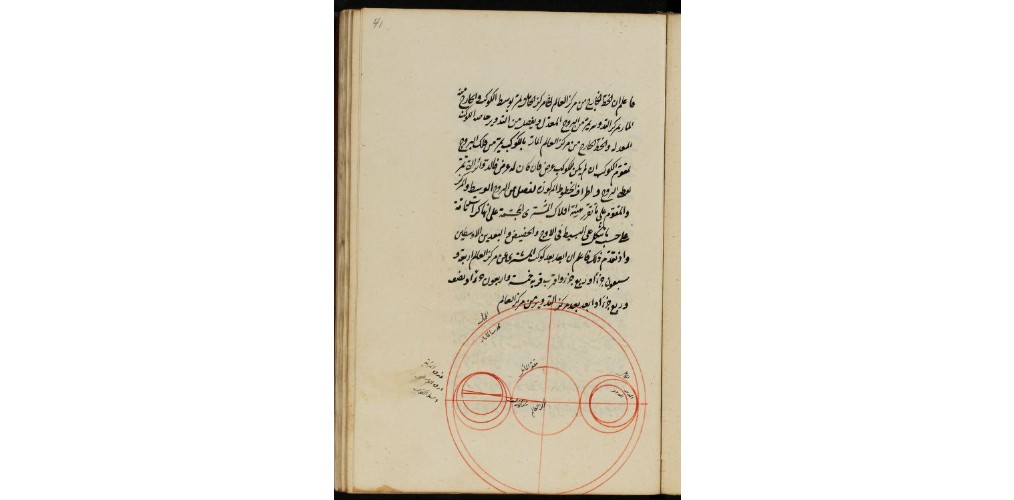

Figure 6. Nihāyat as-Suʾūl fī taṣḥīḥ al-Uṣūl – The rights status of this resource is public domain. Credit: The Leiden University Libraries

However, the study sheds light on areas where Copernicus’s theory drew directly from Ibn al-Shatir. It mentions, for example, the lunar model in which the Muslim astronomer used epicycles to correct Ptolemy’s exaggerated lunar distance variations.

“This is nearly identical to Copernicus’s lunar model in De Revolutionibus,” the study notes. Both reduced the lunar distance fluctuation from Ptolemy’s factor of two to a more accurate range, relying on similar geometric constructions.

“For Mercury and the inner planets, Copernicus’s use of secondary epicycles and the Tusi-couple-like mechanism echoes Ibn al-Shatir’s approach. Ibn al-Shatir’s Mercury model, with its multiplication of epicycles to eliminate eccentrics, reappears in Copernicus’s work.”

Ibn al-Shatir is also celebrated for his Tusi-couple, a mathematical technique and an innovative mathematical device in which he employed additional epicycles to eliminate the equant—a problematic feature of Ptolemy’s system.

The Tusi-couple derives its name from Nasir al-Din al-Tusi, a 13th-century Muslim polymath whose writings include the most accurate tables in antiquity of planetary motions, an updated planetary model, as well as penetrating critiques of Ptolemaic astronomy.

Ibn al-Shatir’s use of the Tusi-couple to simulate linear motion influenced Copernicus, who produced similar adjustments, though Copernicus applied them within a heliocentric framework, the study notes.

The study’s author writes, Both astronomers (Copernicus and Ibn al-Shatir) replaced Ptolemy’s equant with additional circular motions, achieving uniform motion without an artificial reference point.

“Ibn al-Shatir’s solar model, with a new eccentricity and epicycles yielding a maximum solar equation of 2;2,6°, parallels Copernicus’s solar calculations. This suggests Copernicus may have adopted Ibn al-Shatir’s numerical tables or methods, adapting them to his Sun-centered system.”

Asked whether she thinks Copernicus adopted at least parts of his theory from Ibn al-Shatir, Dr. Salama adds:

“Our analysis reveals that Ibn al-Shatir’s treatise, though geocentric in intent, produced results so aligned with heliocentrism that Copernicus’s debt to him is undeniable—two centuries of separation could not erase this intellectual kinship.”

The research findings aim to rectify what the author perceives as a historical oversight by Western scholars, who are frequently alleged in current Arab and Muslim science literature to exhibit Eurocentric tendencies, marginalizing the contributions of Muslim astronomers like Ibn al-Shatir in favor of European figures like Copernicus.

The study holds significant implications for the history of science in the Middle Ages and the European Renaissance. By demonstrating parallels between Ibn al-Shatir’s and Copernicus’s work, it challenges the Eurocentric narrative that the heliocentric revolution was a solely European achievement.

Figure 8. One of numerous astronomical tables found in Ibn al-Shatir’s manuscript, in which he provides details of the lunar and solar eclipses. Credit: The Leiden University Libraries.

In the meantime, it underscores the role of the Islamic Golden Age in laying mathematical and observational foundations, prompting historians to reconsider the global flow of scientific knowledge.

The research goes as far as highlighting the need to update science curricula to reflect a more inclusive history, acknowledging contributions from non-Western scholars.

On the significance of the study, Prof. Hamid al-Naimiy, a renowned astronomer and the research’s main supervisor, said:

“This study is a clarion call to rewrite the history of astronomy, ensuring that the brilliance of Muslim scholars like Ibn al-Shatir stands alongside Copernicus in our collective narrative of scientific progress.”

Asked for his opinion on Ibn al-Shatir’s cosmological model, Prof al-Naimiy, who is also Sharjah University’s Chancellor and SAASST’s director, said that the Muslim astronomer was a pioneer in the Islamic scientific tradition and his treatise :

“…shows that he dismantled the Ptolemaic model and corrected its flaws two centuries before Copernicus. This work emphasizes the significant contributions of our heritage to global astronomy.”

Dr. Salama says:

“Ibn al-Shatir’s empirical refinements within a geocentric framework, paralleled by Copernicus’s adaptation, illustrate how incremental improvements can precede paradigm shifts,” adding that her research “offers a model for modern science, where foundational work in one context can catalyze breakthroughs in another.”

Figure 9. Principles of astrology – Kitab al-tafhim li-awa’il sana’at al-tanjim, or ‘Comprehensive introduction to the principles of astrology’, by the famous Islamic astronomer Biruni. Reference: Or 8349. Credit: Public domain, Qatar Digital Library

5 / 5. Votes 1

No votes so far! Be the first to rate this post.

Muslim Heritage:

Send us your e-mail address to be informed about our work.

This Website MuslimHeritage.com is owned by FSTC Ltd and managed by the Foundation for Science, Technology and Civilisation, UK (FSTCUK), a British charity number 1158509.

© Copyright FSTC Ltd 2002-2020. All Rights Reserved.