The period from the 9th century to the 13th century witnessed a fundamental transformation in agriculture that can be characterized as the Islamic green revolution in pre-modern times. The economy established in the Arab and Islamic world enabled the diffusion of many crops and farming techniques as well as the adaptation of crops and techniques from and to regions beyond the Islamic world. These introductions, along with an increased mechanization of agriculture, led to major changes in economy, population distribution, vegetation cover, agricultural production and income, population levels, urban growth, the distribution of the labour force, linked industries, cooking, diet and clothing in the Islamic world. This article presents a survey on those issues and others, such as agricultural machinery water Management and farming manuals.

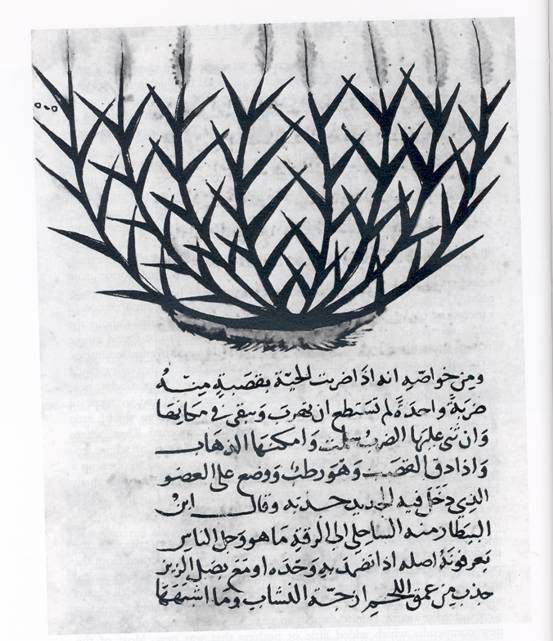

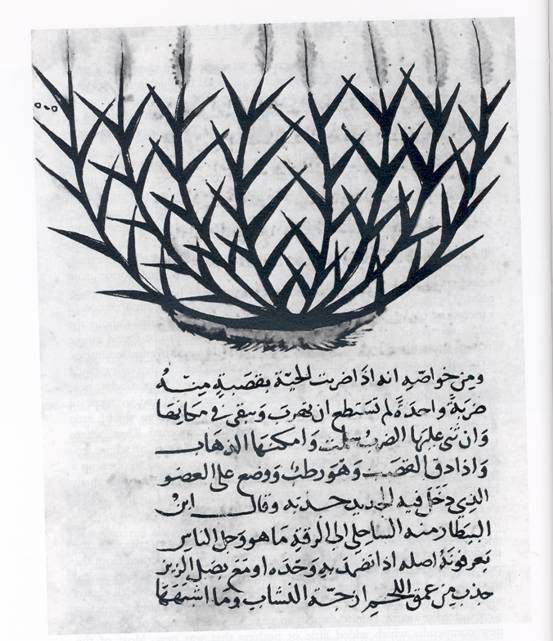

Figure 2. Arabic botanical treatise © Princeton University Library (Source) |

This author, just as any person enthusiastic about Islamic civilisation, particularly in the particular field of this article, has to take note one of the best news of recent times, the arrival of an organisation named Filaha: www.filaha.org. This organisation and what it does, available on the internet, is by very far one of the best things in the field to emerge in recent times so good is its output. It truly cuts down the efforts of any scholar interested in the subject. The quality of information especially on Islamic manuscripts dealing with farming is first class. One of course is not going to try and reproduce what Filaha conveys to us, unless one just cuts and pastes the whole site, and that will be it. For anyone, it is simply better to browse through the Filaha webs-site, and glean all that one wishes to glean directly. Readers of the article by this author only need to pick on such matters that the Filaha project people did not deal with, such as in in the first heading (dealing with matters of distortions, and the final headings in part 2, matters at which this author excels).

In the Introduction of the Filaha project we have a map highlighting the Andalusi school of agronomy which is as simple as informative. The picture of the Tribunal of Waters sitting at the door of the Cathedral is so simple an image, and yet powerful, a true symbol of the dialogue of civilisations, and this excellent part of the caption referring to the tribunal:

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

The site has also a full list of Muslim scholars involved in the subject and countless other pieces of information, which is pointless for us to dwell on here. In words, for any person reading this article, switch to Filaha.org at any moment you can.

This being said, we cannot fail to refer to the scholar who single handeldy revived interest in Muslim farming: Professor Andrew Watson of Toronto.[1] We can safely say that without him, much of what we know, if not nearly everything we know about Muslim farming, we would not know. Professor Watson did not just inform us, he triggered a revival of interest in the subject, or differently put, he opened a new field for everyone to go into. This author remembers how he came across his works in the 1990s and let others know, who then delved into the study of the subject, inspired by, and given the first leads, by Watson. It is perhaps fair to say that much of the enthusiasm for Muslim farming and the abundance of knowledge we have today owes to Professor Watson.

Figure 1. A page from “Kitab al-Diryak. Selciukide/Seljuq Art – See Figure 4 for full page view (Source)

Glick’s works on irrigation in Al Andalus are without a doubt some of the most informative and inspiring. In Spain, in the Valencia region, for instance, Glick elaborates on a complex distribution system of the waters of the River Turia, divided into successive stages, each stage representing the point of derivation of one main canal which drew all the water at that stage, or of two canals, dividing the water among them.[2] In times of abundance, each canal drew water from the river according to the capacity of the canal; in times of drought, the canals would take water in turn, for a commensurate number of hours or a proportional equivalent.[3] The same was true for individual irrigators; and herein lies the genius of the Valencia system, Glick notes: when the canal ran full, each irrigator could open his gate as he pleased, but when water was scarce, a system of turns was instituted. Each irrigator, in turn, drew enough water to serve his needs, but could only do so when every other irrigator in the system had taken his turn, hence insuring a relatively equal distribution of supply, both in times of abundance and of scarcity.[4] This is the sort of attention to detail, written with focus of what truly matters that makes one like reading Glick. His excellent bibliographies and references make the task for anyone interested in the subject a much easier endeavour than it otherwise would be.

Lucy Bolens has done considerably in this field, too. Bolens has studied particularly the sections on soils and irrigation in the writings of the Hispano-Muslims.[5] As with other great scholars, the best thing for anyone is to read her directly, rather than this author trying to paraphrase her. Just an instance here, how Bolens reminds us of a crucial element of early Islamic farming:

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Lines which express a philosophy, which most unfortunately has deserted not just the Muslim world but the rest of the world as well.

One of the most prolific and most informative author on Muslim farming in Al Andalus is the Spanish scholar Garcia Sanchez Expiracion (École des Études Arabes (CSIC), Grenade (Spain). We will make a good use of one of her works further down. Her works are mostly in Spanish and need to be translated into English. Any institution performing this task would be doing a historical favour to the world of scholarship. We can cite some of her works here:

-La diététique alimentaire arabe, reflet d’une réalité quotidienne ou d’une tradition fossilisée? (ixe-xve siècles)

-Eaux Aromatiques et autres parfums a Al Andalus

-Ibn al-Azraq: Uryuza sobre ciertas preferencias gastronómicas de los granadinos,” Andalucía Islamica, vol. 1 (1980).

-El tratado agricola del granadino al-Tighnâri

-Fuentes para el estudio de la alimentacion en la Andalucia islamica

-Normas dietéticas a través de los calendarios andalusies

-la obra médica de Muhammad al-Ilbîrî

-Traducciones catalanas de textos cientificos andalusies en la Corona de Aragon

-Les traités de ‘Hisba’ andalous: un exemple de matière médicale et botanique populaires

What we can notice easily is that our author leads in one particular area: linking plants with their medical benefits.

Fairchild Ruggles wrote an admirable book on Islamic gardens of Spain, and other works besides. However, in the work on the Islamic gardens, we glean a mass of information summing the whole Muslim farming system. The economy of agricultural production, Fairchild Ruggles points out, was a self-perpetuating cycle of profits accrued from trade, invested in agrarian reforms that produced abundant crops and special plants for the export trade, in turn yielding more profits.[7] The profits were reinvested in the land, which yielded greater profits and drove the engine of economic growth.[8] As Fairchild Ruggles notes, the system of crop rotation, fertilization, transplanting, grafting, and irrigation were implanted so rapidly and thoroughly because the legal code governing land-holding and tenancy provided an incentive to improve farming practices and because the upward spiral of economic growth rewarded investment.[9]

Millas Vallicrosa (1897-1970) remains one of the leading fathers of the subject of history of sciences; a first class scholar, of the calibre of Sarton, Haskins, and Wiedemann, that brand of top scholarship now gone. In our field, we have many works as in this note.[10] Millas Vallicrosa enlightens us on the contribution of many Muslim andalusi agronomists, such as Ibn wafid, al Tignari, and Ibn Bassal.[11] Brief focus here is on his edition of a botanical work in Muslim Spain of the 11th century entitled “The physician’s support for the knowledge of plants”, by an anonymous author.[12] Millas Vallicrosa’s description gives us an idea on the meticulousness that defined early Muslim scholarly works.[13] The author of this manuscript lists the names of all plants, whether medicinal or not, giving a separate entry to each under the name by which it was most usually known in classical Arabic, and providing cross-references under its other names. The main entries, so extensive that in some cases they take up several pages, are classified as follows: botanical genus to which the plant belongs, and its different species and

Figure 5. Andrea Cesalpino, 16th C. Botanist (Source) |

varieties; morphological description of each of these, with an analysis of its component parts (root, stem or trunk, branches, leaves, flower, fruit, sap, gum or resin), mentioning the consistency, structure, colour, aspect and other physical characteristics (size. hardness, taste, smell, stickiness, etc.) that distinguish them, defining these by means of comparison with other and more familiar plants and conveying size by the simplest and most obvious analogies, such as the length or thickness of a finger, the height of a man, the length of the arm, and so on. He carefully studies the genus, species and variety of the different plants, gives the names of each plant in different languages, and sometimes he even differentiates between the various local forms of Spanish-al-Andalus (that of Muslim Spain), Galician, the speech of the Upper Marches, describing its geographical location, with particulars of the nature of the soil in which it grows, the regions where the author has seen it or gathered it or ascertained that it is to be found; not omitting the use of any such plants, medicinal or other purposes, and an infinity of detail, and search for perfection which astounds us today.[14] Millas Vallicrosa points out, the work of this 11th century Muslim Andalusian botanist, who was closely associated with other botanists, such as Ibn Bassal and Ibn Luyyun-both of Toledo-makes him an obvious forerunner of the modern system of classification of flora invented by Cuvier, for which the only precedents hitherto encountered-and those very imprecise-had been those in the work of the 16th century Italian botanists, Cesalpino and Matthioli.[15]

R.B Serjeant’s erudition is evident in his diverse works on Islamic subjects. Here we mention his essay on the influence of Muslim farming,[16] a short essay, and yet, one that opens so much scope for anyone seeking to delve into the subject. Serjeant informs us about Islamic legislation in respect to land and water ownership and management. Serjeant enlightens us on the Yemeni contribution to irrigation, their skill in the control of flood waters, and related subjects, including also their influence on the systems of North Africa and al Andalus.[17]

Following the praise to some comes the shaming of others.

Cherbonneau remarks:

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

This author has constantly raised the issue of distortions of Muslim history, faith, culture, and civilisation. Whether you read about colonial history of the Muslim world, or the history of the crusades, or the history of history of sciences, or the arts, or engineering, or the history of piracy, or the plight of women, or Black people, that is any subject, the Islamic role in them is fundamentally distorted. The omissions, the errors, the plain distortions, the claims not matching facts, the disappearances of whole periods of history, centuries even, the disappearance of sources, of first class material, of whole collections of archives, in fact, is simply staggering.

Let everybody know: it is not that this author is a genius who has discovered something that others have not. As we just saw with Cherbonneau, many Western authors, and even Prince Charles himself have referred or noted the vast field of distortions of Muslim accomplishments in sciences and civilisation just as in other fields. As brief instances here, Harley and Woodward have noted this in respect to cartography,[19] Hill in regard to technology;[20] Smith in respect to dam construction;[21] O’Connor and Robertson in the field of mathematics;[22] and we can go on and on.[23] Some scholars such as Menocal have also remarked how it is even suicidal academically to try and rectify the picture in favour of Islam.[24] So, to conclude, it is not that his author has made the discovery of the century. He did not. So, here, we look at the techniques used to distort the subject of Muslim farming. We focus on three methods used to distort the subject through specific instances on how it is done, and how reality fundamentally contradicts the claims made by the distorters.

This technique is the most common. It consists in supressing from knowledge facts and sources of facts that relate to the role of Islamic civilisation, or anything favourable to Islam. For instance, anyone reading through the history of farming would, in 90% of the literature at least, find no reference whatsoever to any Islamic contribution in the field.

One of the established assumptions is that, just before, or around, the early-mid 18th century, farmers in the English countryside initiated what is commonly known as the agricultural revolution. English landed classes, it is explained, were helped by the enclosure of land (began in 16th century), which gave them both security and institutional foundations to innovate. This led to widespread and critical changes such as crop rotation, improvements in animal husbandry, farm experiment, and further improvements. By the mid-late 18th century, English agriculture, it is explained, managed to release both surplus capital and labour for industry, and provide a wide enough market to give the foundation for the so called Industrial Revolution that began in the late 18th century. Further changes (greater and better use of fertilisers, improved animal rearing, mechanisation, and the like) in England and the rest of the Western world took place in earnest and, as time passed, reached a high momentum, completely reversing the picture that prevailed in past centuries, with poor food production now being replaced by large food surpluses. Simultaneously there was an equally momentous reversal on the wider international level, food purchasing orders now came from the southern countries, which have become unable to feed their fast rising populations, whilst as recently as the 19th century, it was the opposite, France, for instance, purchasing wheat from Algeria.[25] In fact it was an unpaid French debt of Algerian wheat that triggered the French colonisation of Algeria.

Figure 6. Ancient Egyptian agricultural knowledge predates that of the West (Source)

How do we get mislead about this subject as others? Simple! If we read about the Western agricultural revolution and not consult anything about Islamic accomplishments in the field we will never know the reality. In this field, as in others, if no Westerner writes about Islamic accomplishments we think they never existed. Let’s take engineering and technology, for instance. Wiedemann, true, wrote about Muslim accomplishments in the field, but that was late in the 19th and early in the 20th. Because nobody wrote anything, it seemed Muslims had accomplished nothing. It only took Donald Hill writing in the 1970s and after for everyone suddenly to realise that the Muslim legacy in the field was considerable, in fact was crucial. The same about agriculture. As we shall see, it is only thanks to Andrew Watson that we suddenly realise that the Muslims have accomplished a lot, indeed, and that they were centuries ahead of the rest.

So, besides omissions, there is another technique to distort the subject, by demeaning the Muslim role. Ashtor claims, for instance:

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

The information which the Arabic authors provide us in the methods of agricultural work, besides the irrigation canals and engines, is rather scanty. But collecting these records from various sources one is inclined to conclude that the Arabs did not improve the methods of agricultural work. There is only slight evidence of technological innovations in near eastern agriculture throughout the Middle Ages, whereas the history of European agriculture is the story of great changes and technological achievements.[27]

The Egyptian historian al-Makrizi says that the harvests had diminished so much under Moslem rule that it was necessary to put aside a quarter of even a third of the crop in order to render cultivation profitable.[28] Undoubtedly the Arabic author had the later Middle Ages in mind. But the decrease of the crops had probably begun a long time before he wrote. It was the consequence of neglect, of old tired methods of cultivation, of heavy taxation and the attitude of a short sighted (Mamluk) government.”[29]

Ashtor dwells on Mamluk incompetence, rapacity, neglect, and they being at the foundation of the Islamic collapse, claiming for instance,

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Ashtor is promoting fallacies, which the subsequent sections will deal with at great length, but a brief refutation of his views is made here.

Firstly, with regard to the particular claim that Muslim agriculture was a mere copying of Nabatean farming, the following outline will show that nearly all Islamic innovations in farming were accomplished in the medieval period, thus, centuries apart from the Nabatean model. It will also show that they relate to this model hardly at all, and that, the faith itself, the geographical expansion of Islam, besides experiment on the land, followed by the recording of such experiments in farming treatises, and most of all the outburst of scientific activity in engineering, metallurgy, and other fields, which were the real foundations of the Muslim agricultural revolution. Had Ashtor consulted the works by Serjeant and others he would have understood that it was the revolution brought by Islam that was at the foundation of so much that affected the sector. As for Muslim farming being derived from Nabatean agriculture because the work of an early Islamic farming treatise by Ibn Wahshiya (860-ca 935) is entitled Filaha Nabatiya,[31] there is no better way to answer this issue than Watson’s following observation:

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Figure 7. A Mamluk nobleman from Aleppo, 19th century (Source) |

The second claim by Ashtor that the Mamluk rulers of Egypt and Syria did little or nothing to build and maintain engineering works is likewise based on a total disregard for historical facts. Briefly, here, one can cite Lapidus’ thorough study to show the Mamluk role in the construction of canals and other irrigation structures. Aleppo, for instance, had suffered greatly from the Mongol attacks in the second half of the 13th century, and only after 1312 when the danger had passed were water works begun to recreate the city’s former greatness and sustain larger garrisons and a restored or even growing population.[33] Between 1313 and 1331 Governor Sayf al-din Arghun, completed work on a canal from the River Sajur, 40,000 cubits long, costing, according to most estimates, about 300,000 dirhems, but possibly as much as 800,000. Half of the expense was borne by the governor and the other half by the Sultan.[34] No investment on that scale is recorded anywhere in the Christian West, for instance, during that period, and for many centuries after. This basic investment was followed in the next half century by the construction of fountains throughout the city and branch canals to feed them. Most of these fountains were built by emirs and governors.[35] Some canalizations were begun before Timur Lang, but his invasion (1398 onwards) interrupted the projects, before important and vital works continued to be carried out at Mamluk initiative and expense.[36]

Butzer and his followers claim that the Muslims did not fundamentally alter the available range of cultivars and technology, and that if it might seem they brought changes to Spanish farming this was simply due to the fact that before them there was a catastrophic decline.[37] Thus, rather than introducing agricultural changes, Muslims only restored the prosperity that had been lost after the collapse of the late Roman Empire.[38]

Butzer and his group are wrong, for most of the changes the Muslims brought about were completely unknown to the Romans. Had Butzer and his group been correct in their claim that Islam had little to do with the changes in Spain, they would have found a revolution in farming taking place in other places in Christendom equal in tenor to that taking place in Muslim Spain. Yet, this is not the case, whether in pre-medieval or in medieval Christendom. Nowhere do we find any advances comparable to those that took place in medieval Islamic Spain; advances, however, shared throughout the medieval Islamic land from the far east to the far west.[39] Besides, and specifically in relation to irrigation, the Spanish vocabulary in the field demonstrates a very strong Muslim influence, in fact nearly the whole vocabulary is derived from Arabic.[40] Furthermore, as Cowell notes, the Spanish Muslims skills in irrigation and in terracing have resulted in an agricultural productivity far beyond the wit of ‘the relatively barbarous, less cultivated native Spaniards.’[41] In fact, as will be abundantly shown in this chapter, the changes Muslims made in the field were not just dramatic; the Western agricultural revolution would incorporate such changes as rotation of crops, better use of fertilisers, experimental gardens, and others, only five to six centuries after the Muslim world, from the 16th century onwards.

Also under Islam, agriculture got more produce out of the land by bringing more land under cultivation and by making old land much more productive than in the past.[42] It was highly capital intensive, and highly labour intensive; more capital being invested in the construction of irrigation works, terracing, providing seed and fertilisers, the reclamation of land, which also required heavy investment in labour, as well as in tools, animals and outbuildings. It is necessary to go back to the irreplaceable works by von Kremer, as translated by Khuda Bukhsh, and then find evidence of the vast engineering works for agricultural purposes begun in the times of Omar ibn al Khattab (Caliph 634-64) or under the Ummayads, especially under the stewardship of the Viceroy, al Hajjaj (d.714.)[43] The introduction of new crops by Muslims, as we will see below, had the same effect of increasing production, productivity, higher investment of capital, labour, research, innovations (both on the ground and as recorded in treatises), and better use of the soil. The combination of all such factors brought former dead land into cultivation, and new irrigation techniques and systems also contributed to this.[44]

Another instance of demeaning is by Adams, who in his Land Behind Baghdad, draws the conclusion that the density of settlement in the Diyala Plains in Islamic times, as well as the extent of the irrigation system, never reached the high point of later Sasanian times in spite of considerable reconstruction in late Umayyad and early Abbasid times.[45] His conclusions, however, as Watson points out, are based on inadequately collected data, such as his figures on taxation, which fail to take into account changes in rates of taxation, or efficiency of collection, and that his archaeological data is also inadequate due to his limited choice of samples, and so is Adams’ incapacity to distinguish between the rural pottery of the Sasanian, Umayyad and Abbasid, shortcomings that impact directly on the wider picture and its relation to irrigation, and thus, render his conclusions wholly distorted.[46]

Watson sums up and refutes many misrepresentations relating to Muslim irrigation:

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

There is criticism, and there is criticism. If any nation, just as any person, spends their lives without any self criticism, i.e not admitting their flaws, and not trying to correct them, such persons, or nations, never change for the better. In fact nations or individuals who always dwell on their grandeurs when horrendous flaws characterise them, as history, without fail, has shown us, kept deluding themselves until one day they collapsed and never rose again. So, criticism or awareness of one’s flaws is an absolute necessity in order to correct them. However, there is another type of criticism, which aims to create an inferiority complex in the other, making them so much believe in their vileness or meaninglessness. It kills any sense of creativity, or ambition, or aspiration. This is unfortunately what the Muslim nation submits to, or has been submitting to for a quite long time. As we know by now, its accomplishments are hidden away, and its representation is that of a barbaric nation. A number of journalists, politicians, religious figures, scholars, and leaders of opinion, frequently hit Muslims with such virulence that Muslims under the shock are silenced. Let’s here cite a French scholar, Louis Bertrand, a member of the French Academy writes about the Muslim legacy in the field:

Figure 8. Louis Bertrand, French novelist, historian and essayist (Source) |

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

But not only did the Arabs make a desert there and introduce drought and sterility by their deforestation.[54]

The admirable Spanish peasants who in the distant days of the Roman hegemony, gave Betica its reputation, and who nowadays have succeeded in restoring in French Algeria the fertility destroyed by the carelessness and barbarism of the Arabs.”[55]

Let’s set aside the fact that Bertrand truly dislikes Arabs. Let’s just focus on the fact that, unlike him, others closer to facts and reality could witness directly the Muslim accomplishments. Hence, Jeronimo Munzer, an important nobleman who travelled through Spain in the years 1494-5, when a great many Muslims still remained in Aragon, tells us:

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

In the 16th century, for instance, King Philip II of Spain’s secretary, Francisco Idiaquez extolled the skill of the descendants of the Muslims in improving the Iberian landscape:

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

In support of the latter views, it is known that such was the Muslim superiority in farming skills, and the dependence on such skills, that following the mass elimination of the ‘Moors’ from Spain in the years 1609-1610, churches and land proprietors lost considerable incomes.[58] The Duke of Grandia suffered especially from this; all the operatives in his sugar mills were Muslims, no one else knew the processes.[59] In Ciudad-Real, the capital of La Mancha, the cloth industry was ruined.[60] Even a large part of the kingdom of Valencia, the garden of Europe, was for years an inhabited wilderness.[61] The tabla de los depositos of Valencia-presumably a bank of deposit-was bankrupted, and the tabla of Barcelona, which was regarded as exceptionally strong, was likewise bankrupted.[62] Such was the scale of the losses that the nobles were annually assisted by the king, as though they were in danger of starving. The Count of Castellar was awarded the sum of 2000 ducats a year, Don Juan Rotla 400, the Count del Real 2000, the Duke of Grandia 8000, and so forth.[63]

Let’s now outline some of the Muslim accomplishments in the field of farming.

Watson, in one of his shorter works, appropriately entitled ‘A Medieval Green Revolution,’ holds that:

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Figure 9. The animal-powered sakia irrigation wheel was improved in and diffused further from Islamic Spain (Source)

Medieval Muslim farming, in its dominant traits, methods and techniques, was much more advanced than that of the Christian West. It was to remain so for centuries thereafter. Records show that cereal yields in Egypt were around 10 for 1, yields which were only to be obtained in Europe at the end of the 17th century.[65] At the time when crops regularly failed in Europe and caused terrible famines, the diffusion of new crops and improved cultivation in the Muslim world meant that fields that once yielded one crop yearly before, now yielded three or more crops in rotation.[66] Agricultural products met the demands of an increasingly sophisticated and cosmopolitan urban population, providing it with a variety of products unknown in northern Europe.[67] Throughout the Muslim world, cities were supported by a very advanced farming system that included extensive irrigation works, expert knowledge of agricultural methods, the best orchards and vegetable gardens, the rearing of the finest horses and sheep, ‘the most advanced system in the world,’ says Artz.[68] Arriving crusaders in the East were stunned at the sight of the coastal regions of Syria and Palestine. Tripoli and its surrounding were covered in cultivated fields, and an abundance of orchards and gardens, vast plantations of sugar; citrus trees, banana plants, date palms… all thriving.[69] Dunayat (in northern Syria) was lying on a vast plain, surrounded by sweet smelling plants and irrigated vegetable gardens, according to the same crusader account.[70] Under Muslim rule, the south of Spain became a highly prosperous region, and as described by a poet quoted by Shack:

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

The al-Jaraffe district, to the west of Seville, in the 12th century, was, according to all accounts, covered in so luscious fruit orchards that ‘the sun hardly touched the ground.’[72] In that same country, such was the quality of produce some wheat could keep for a century in adequate storage conditions.[73] In Sicily, Lowe holds, practically all the distinguishing features of Sicilian husbandry were introduced by the Muslims: citrus, cotton, carob, mulberry, sugar-cane, hemp, date palm, safron… the list is endless.[74] Bresc, Glick and Castro also find that virtually all of the technical farming jargon of Spain and Sicily derives from Arabic.[75] Such was the Muslim expertise that in Sicily, agriculture remained in Muslim hands under early Norman rule, and was, according to Scott ‘carried to the highest perfection.’[76] This expertise meant that every plant or tree, whose culture was known to be profitable and which could adapt itself, was to be found in the gardens and plantations.[77]

Muslim expertise also stretched to methods of fighting insect pests, use of fertilizers, grafting trees, crossing plants to produce new varieties, etc.[78] On grafting alone, according to Scott, the Spanish Muslims employed eight distinct methods. Muslims, according to him, were also able to treat with success diseases of all known species of ‘the vegetable kingdom;’ and were exceedingly skilful in the distillation and refining of essences, and the cultivation of great plantations of flowers for the sake of the exquisite perfumes they afforded, and in preserving fruits for an indefinite period.[79] Horticultural improvements, Sarton notes, constitute one of the finest legacies of Islam, and the gardens of Spain proclaim to this day one of the noblest virtues of the Muslims.[80] Many indices, Bresc says, allow the formulation of the hypothesis that the technical legacy of the gardeners of the Palermo plains has been inherited from the Islamic period, and also brings closer Sicilian horticulture to that of Andalusia.[81]

Muslims introduced many new crops which impacted considerably on the local economies and societies of many places. In West Africa, for instance, villages became larger and more numerous as new crops, introduced in Islamic times, made the soil much more productive than it had been.[82] In Spain and Sicily, under Muslim influence, a silk industry flourished, flax was cultivated and linen exported, and esparto grass, which grew wild in the more arid parts, was collected and turned into various types of articles.[83] Glick notes how the introduction of new crops combined with intensification of irrigation, gave rise to a complex and varied agricultural system, whereby a greater variety of soil types were put to efficient use.[84] In Spain, wherever artificial irrigation was possible, in the Andalusian Vegas, the Huertas of Murcie and Valencia, all crops, including tropical plants, flourished, and brought in huge economic benefits.[85] The same happened in Sicily, where practically all distinguishing features of its husbandry were introduced by the Muslims: citrus, cotton, carob, mulberry, sugar cane, hemp, date palm, saffron….[86] Many constitute the foundations of the Sicilian economy today.[87] This Islamic impact is highlighted by the fact that the plants grown in Sicily are well elaborated upon in Muslim farming manuals; a rich variety which contrasts with the dearth of crops from northern European farms.[88]

The impact of such new crops on activities, other than agriculture, was equally dramatic. The introduction of new crops first led to sharp rises in employment, most often outside agriculture, and the workers who carried out diverse tasks related to the exploitation and manufacture of such new crops at diverse stages, sold both their products and labour on the market.[89] Other tasks required such a degree of skill or such expensive equipment that they were often carried out by a specialised labour force.[90] The new crops also stimulated the development of new methods and machinery, for as Forbes remarks, they would not have been grown or used with the typically classical agricultural methods.[91] Rice, for instance, could be milled by hand operated querns in the home but also, and most often, the task was accomplished by mills powered by animals, water or wind.[92] The new crops impacted considerably on trade, both local and foreign. Cotton, (and cotton thread and cloth), rice, sugar, coconuts (as well as the fronds, branches, and trunks of the coconut palm), and doubtless other new crops were traded over long distances in the Islamic world.[93] Some were exported on a large scale beyond the Islamic world, sugar and cotton, for instance, were sent to many parts of Christian Europe.[94] This trade generated an important class of intermediaries trading in foodstuffs, and these merchants, in turn, were serviced by transporters, financiers, and warehouse owners.[95]

Figure 10. Ibn al-Baytar (d. 646 H / 1248 AD): Tafsir kitab Diyasquridus fi al-adwiya al-mufrada (A Commentary on Dioscorides’ Materia Medica) (Source)

Trees played a fundamental role in early Islamic civilisation. Prophet Mohammed constantly reiterates the need for protecting trees, and the necessity for planting more. We will look at his sayings in this field which are quite abundant in part 2 of this work. In following the line adopted by the Prophet, medieval Muslims showed an ingenuity, which far surpasses that of any culture to this day. The excellent article by Garcia Sanchez Expiracion: Utility and Aesthetics in the Gardens of al-Andalus: Species with Multiple Uses,[96] enlightens us on this. Gregorio de los Ríos (16th century), in his Agricultura de jardines [Agriculture of Gardens] when discussing those plants that should be included in the garden, wrote:

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

De los Rios dismisses the ornamental value of the shade provided by trees, which, in stark contrast, was an element that was highly appreciated by Muslim authors, from both an aesthetic and functional viewpoint. Trees were used by Muslims to delimit boundaries, a practice that took place in royal almunias and the gardens of family homes, wherein both aesthetics and functionality played a part, and which involved fruit trees, trees with a long tradition within Mediterranean agriculture and recently acclimatised species. A highly explicit example is provided by the Arab historian Ibn ‘āl sahib al-Salāt (12th century) in relation to the garden and the edifications of the Bukhayra in Seville, the “almunia” that best represents the Andalusian Almohad period, who encouraged the planting of trees of all kinds.[98]

Tree species were planted with the objective of producing shade, resulting in shaded avenues and walkways within and around the city such is the case of the tree- lined avenue constructed in Granada in the 11th century.[99] Descriptions of areas under the shade of tall trees and the sensation of coolness therein provided is vividly reflected in the poetry of the al-Andalus period, particularly the work of Ibn Khafāja (11th century). In addition to providing those frequenting these areas with a sensation of coolness, they protected particularly vulnerable plants from the searing sun, such as certain recently introduced species. Several varieties of trees, fully integrated in the landscape and agriculture of al-Andalus as a legacy of previous eras, are mentioned and defined as being of multiple use by agronomists and botanists. Such is the case of the pine (Sanawbar) and the cypress. Mention is also made of the use of pine kernels in cookery, whilst al-Tighnarī, referring to the medical applications of this tree, states that if its bark is boiled with nigella (shūnīz) and applied as a bandage, it aids dental ailments.[100] In the case of the cypress, certain of the uses assigned to this tree aid the achievement of an ornamental ideal, whereby it acts as a base that improves other recreational elements: for example, its wood, given its insect-repellent properties, provides a perfect source from which to construct the trellis-work that lines the pathways of almunias and gardens.[101] Al-Tighnarī ascribes various medicinal properties to the cypress, involving the nuts leaves and bark of this tree, which, amongst other functions, were used to treat skin infections, to dye the hair black and strengthen nails, as diuretics, as obstruction dissipators, as haemostatics and as a cure for intestinal and stomach ulcers.[102] In addition to the evident ornamental characteristics of the laurel (rand, ghār), “a tree with a beautiful aspect”, that is particularly recommended in gardens containing myrtle and other aromatic species, the agricultural texts assign numerous uses to this plant, which is cited variously as an insecticide, a component in veterinary medicine.[103] The hackberry was one of the most highly valued trees in the gardens, farms and agricultural estates of the Andalusi period, indicating the passage of irrigation ditches and water courses and delimiting paths and boundaries.[104] The elm tree olmo (nasham) is one of the species that is assigned the greatest number of uses: it is attributed with ornamental functions, providing shade over wells, stone benches and irrigation ditches, planted close to garden walls and towards the north and at entrances, in order to avoid damage to garden trees and vegetables. It is also planted in humid areas and open spaces. The elm was also used to manufacture vine arbours and various utensils, given the quality of its wood. Lastly, the elm is cited as a result of its numerous medicinal benefits.[105] Its roots were crushed and applied via a compress in order to disperse tumours and alleviate fractures, pain in articulations and sprains, a method that also proved very effective in the process of accelerating pus drainage from an abscess. The liquid in which the roots were boiled provided very good results in the relief of ailments affecting sight and hearing.[106] The pomegranate tree (rummān) representing one of the plants for which Mohammed expressed his admiration.[107] The uses attributed to this tree by Andalusi agronomists are very similar to the current uses ascribed to the plant and include its employment as an ornamental feature and its use in hedge creation. In terms of the tree’s medicinal uses (in addition to various others, including use in veterinary medicine, agriculture, etc.). Al-Tighnarī cites the following: the juice of the fruit, mixed with additional ingredients, is employed to treat eye conditions (particularly to remove corneal staining) and to combat infection. The syrup of the sweet variety is a remedy for coughs as it relaxes the chest and facilitates expectoration and the evacuation of the bowels, whilst the syrup produced from the acidic variety of pomegranate acts as a stomach tonic and eliminates bile. It is also used as a diuretic and to alleviate heart palpitations.[108]

Figure 11. The Patio de la Acequia Granada, Spain (Source)

Watson sums up for us the remarkable union of wits which once upon a time marked Muslim culture:

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

We take a simple instance to highlight the infectious character for all that was good that in the past marked Muslims. We refer here to the diffusion of some fruit varieties. Certain varieties of pomegranate, including the ja’farī, also known by names such as safarī [“traveller”] as a result of the tales surrounding its Eastern origin, arrival in al-Andalus and acclimatisation in the cordovan court of the emir Abd al-Rahmān I. Certain authors locate its origin in Baghdad, whilst others cite Medina, stating that it descended from the variety that was planted in this city by the Prophet. All of this is described in minute detail by the agronomist al-Tighnarī and compiled by Ibn al-Awwām.[110] The pomegranate tree (rummān), a species that originated in the Near East, was cultivated and dispersed throughout the Mediterranean basin from a very early stage and numerous varieties of this plant now exist. This tree is highly venerated within Islamic tradition, representing one of the plants for which Mohammed expressed his admiration, stating: “the fruit of this tree dismisses all vestiges of rancour and envy”.[111] Another fruit, the Safari fig, was introduced from Damascus by the chief judge of Cordoba, and a Jordanian soldier named Safar took a fig cutting and planted it on his estate in the Malaga region. This species, called safari after the soldier, subsequently became widely diffused.[112] The agricultural writer Abu al-Khayr (probably 11th century) mentioned that in 225H/840 the poet Yahya al-Jazal smuggled inside a stack of books the seeds of a new variety of fig, called al-Dunaqal, from Byzantium into Cordoba, where they bore fruit.[113] The stories of the Safari pomegranate and the Dunaqal fig, Ruggles points out, demonstrate that plant species did not merely arrive by chance in al-Andalus; they were sought after, procured, and cultivated with great care in experimental gardens until they were naturalized and could grow and be propagated in al-Andalus.[114] We will see in a heading below a whole list of plants introduced and disseminated by Muslims, which literally transformed agriculture. The spirit of experiment that was very much current in the Islamic world, at that time was a spirit common to the astronomer, the chemist, and the farmer. This spirit of introducing, experimenting, disseminating of plants, or curiosity, or anything of the sort, is missing today.

A crucial factor that stimulated not just the Muslim agricultural revolution, but the whole Muslim civilisation was its open, frontier-less, mobile world, which encouraged movement of people for a variety of purposes. Early Islam was, indeed, marked by a great urge to travel, whether to study Islamic tradition, especially from a reputed scholar, or for trade, or pilgrimage.[115] In this vast process of movement by all classes and groups of people, Eastern Muslims took with them to the west, and those in the west took with them to the East, the habits of their homelands, and acquired new ideas, tastes, and objects.[116] Amongst such travellers were peasants and farmers, to whom must be added traders, scholars, and also envoys sent by rulers who sought to enrich their gardens, all such travels accounting for the movement of crops, irrigation technology, and farming techniques, which were carried principally from east to west.[117] This stimulated considerably the rise of agriculture, just as it did with every other science.[118]

Early Muslim rulers were equally passionate about plants, gardens, water and greenery, and such passion played a major part in the rise of Muslim agriculture. An early promoter of farming was the Umayyad ruler, Abd Errahman I (r. 755-788), who, as soon as he took control in Spain, sent an expedition to the Levant to collect material for his garden in Cordova.[119] The Banu Di Nun ruler, Al-Mamun of Toledo (r. 1043-1073), had the magnificent and beautifully named Bustan al-Na’ura (The Garden of the Noria) erected, in which was constructed Qubbat al-Naim (The Pleasure Dome), which fill the lines of poets.[120] Other rulers with a similar passion for gardens and greenery dominated the early centuries of Islamic rule, from the Aghlabid rulers of Tunisia, the Tulunids of Egypt, to the Almoravids of Morocco.[121]

In farming, just as in learning, the faith, Islam, played the defining role. Scott tells us;

How the Muslim, mindful of the precepts of the Qur’an that inculcates industry as a virtue and stigmatises idleness as a crime, was the most laborious and successful of agriculturists, the most skilful of artisans.[122] Constant, indeed, is the Qur’an urge to labour and make the land fruitful.

Pre-Islamic taxes stood in the way of innovations, and favoured both large estates and the serfdom of the peasantry.[123] Tax laws, inspired by the Qur’an and Islamic jurisprudence, on the other hand, affected different types of land and multiple kinds of crops, and compared to pre-Islamic times, or later times, these taxes were relatively low.[124] Low rates of taxation helped stimulate the cultivation of the land and its improvement, and kept alive a class of smaller, independent landowners and a relatively prosperous peasantry.[125] Under such a system of low taxes, landowners and tenants alike were secure in the knowledge that they, instead of the state, benefited most from their hard work, innovations and improvements to the land.[126]

The Islamic legal corpus, once more, brought changes that removed many obstacles to land exploitation. The Prophet ruled that the person who brought into cultivation land that had been “dead” or uncultivated for more than three years should gain outright ownership of this land; moreover, such land, when it began to produce, was to be taxed only at one tenth of its produce and no higher which was otherwise allowable.[127] Canals dug to bring water to dead lands also belonged to those who dug them, and wells and qanats made in dead lands in order to revive them also belonged to those who made them.[128] This law may therefore have been a powerful force favouring the expansion of sedentary agriculture over grazing, and pushing back the frontiers of settlement into the desert.[129]

Favourable institutional conditions, which prevailed in Islam, also freed the countryside from many arrangements that were economically retrograde.[130] Under Muslim rule, the condition of the serfs was greatly improved, whilst tribute was regulated by law, and ceased to depend upon capricious demands.[131] Lowe observes how, for Sicily, Muslim rule was an improvement over that of Byzantium.[132] There, the latifondi were divided among freed serfs and small holders, and agriculture received the greatest impetus. Thanks to Muslim law, uncultivated land became the property of whoever first broke it, thus encouraging cultivation at the expense of grazing.[133]

Various contractual forms and arrangements inspired by Islam also stimulated agricultural production, such as in al-Andalus, where the worker (‘amil) paid rent to the owner (munasif) in the form of a percentage of the harvest.[134] Since both parties stood to gain from a bumper crop, there were incentives to improve the land and methods of cultivation.[135]

According to Bolens, Muslim farming owed its success to:

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

This success followed two guiding principles: experimentation, and diffusion of acquired knowledge. Levi Provencal observes that Muslim farming literature although suffering an unjust neglect on the part of scholarship, is the only literature which has a ‘flavour of the land.’[137] The treatises reflect, as a rule, both a theoretical and a practical outlook, with a clear balance achieved between a rigorously pursued bookish culture on the one hand and personal experimentation on the other; they exhibit a harmonious and integrated concept of agriculture, considered as a balanced development of nature.’[138] Ibn Bassal, who was gardening in Toledo when it fell to Christian conquerors in 1085, wrote almost exclusively from his own direct experience.[139] Ibn al-Awwam writes:

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

For this purpose he cultivated a short distance from Seville, a farmland called ‘Alxarafe.’[141] His Kitab al Filaha (Book of Agriculture) was a culmination of both practice and observation, and of high technical interest.[142] Ibn al-Awwam’s countryman, Ali Ibn Farah, also experimented with botanical gardens in the most inaccessible parts of southern Spain, and created a botanical garden in Guadix.[143]

Farming manuals produced by these Muslim scholars played a central role in the agricultural revolution. In Sicily, Bresc notes, the many techniques described or suggested in the contracts of the 14th and 15th centuries were found in Muslim farming manuals.[144] Many ploughing methods to prepare the soil, the use of fertilisers, planting, are found to be shared by Sicilian agriculture and such manuals.[145] It is the sort of information found in Al-Ichbili’s Kitab al-Filaha, which goes into minute detail on how to grow olive trees, treatments for tree diseases, grafting, harvesting olives, refining olive oil, conditioning of olives; or cotton, its required soil properties, soil preparation, use of manure, ploughing techniques, the time of the year for planting, irrigation, care for plants, harvesting, and the like.[146] Ibn Wafid (b. 998-99 or 1008, d. 1075), the author of Collection (Compendium) (Majmu’a), had complete mastery in agriculture and was knowledgeable in its procedures.[147] He deals with soil types; water and how to detect its presence in the soil; the most propitious seasons for building farmhouses; fertilizers; seed selection; things that damage grain (such as hailstorms); when to sow wheat and barley; when to reap; beekeeping, pigeon keeping, and pesticides such as myrtle and cumin.[148]

A major contribution to the advance of farming was the focused study by such manuals on specific crops. In respect to cotton, for instance, Qustus al-Rumi says it requires continuous irrigation, and Ibn Luyun states that it needs weekly watering.[149] According to Ibn Bassal, there are two systems of growing cotton in the Islamic world: the Spanish system, by which the plant is irrigated every fifteen days after it reaches a finger’s height, and the Syrian system, by which the land is irrigated once before planting, again when the plant has reached the height of the palm of the hand, and thereafter every fifteen days until the middle of August.[150]

It was Muslims who combined the use of traditional instruments with newly developed ones, such as the astrolabe, and adapted them to agricultural use. The astrolabe, for instance, is recommended by Ibn al Awwam for the purposes of levelling land.[151] These instruments, of Eastern origin, are usually made of iron, and are also very diverse.[152] A study published in 1990, making a systematic account of all the instruments mentioned in all the Andalusi works (both those edited and those still in manuscript) reveals an enormous variety of instruments, eighty in all, of which sixty are properly speaking tools, while the rest are accessories.[153] Most noteworthy are the tools used to level the ground, like the murjiqa,[154] derived from Spanish murciélago meaning “bat”, which is mentioned by al-Tighnari and Ibn Luyun. This may also be the same instrument that Ibn al-’Awwam (following Abu‘l-Khayr) uses in levelling waters and calls marhifal.[155] Another instrument, used to scratch the earth around the roots of trees, is the shanjul, possibly derived from sanchuelo, a term of romance origin, documented by Abu’l-Khayr to designate a utensil which is “a kind of human hand with three cutting clubs.”[156]

Muslims pioneered in many areas that were later on to be identified with the European agricultural revolution.[157] This outline is not the place to look at Muslim agriculture and its vast accomplishments in detail. The site noted above Filaha.org, Bolens and Watson, in particular, are excellent sources that can be used for this purpose.[158] In the following we will simply aim to sum up some of the major accomplishments of Muslim farming, beginning with how Muslims used and managed their water resources.

A major accomplishment of Muslim civilisation was its legal code around water use and management. As Serjeant points out, a considerable part of most Islamic legal books is devoted to water law, a subject, which incidentally, he notes, has not been studied in Europe to any appreciable extent.[159] This legalistic approach to the resource, once more, derives from the faith itself, the place of water in the Qur’an being one of the most predominant, a great number of verses touching upon it in one form or another. The Prophet himself had said much about rights to water and had settled many irrigation disputes, and from his sayings and rulings, worked over by later jurists, there emerged a substantial corpus of irrigation law which clearly established the rights of the parties involved in all sorts of disputes.[160]

Figure 13. Cross-section of a Qanat (Source)

The Shariah, the Islamic system of law, distinguishes three types of water sources which may be the object of use and ownership: water from rivers, from wells, and from springs.[161] In relation to water taken out of rivers, for instance, where it is possible to cause shortage to other users, by e.g. digging a canal to take water from higher up the river, or where damming or the allocation of fixed times is necessary to provide enough water for irrigation, in such case, the river is normally regarded as the joint property of the riparian cultivators, and the question of how much water may be retained by the highest riparian cultivator depends on differing circumstances, such as the season of the year, the type of crop irrigated, and related issues.[162] After qanats came into widespread use in the Muslim World, a body of customs and law (shari’a) developed to regulate the water-supply system.[163] Although this legislation did not always work towards the optimum economic use of land and water, Watson points out, it was a distinct improvement over the water law of pre-Islamic times of many of the regions affected. In much of pre-Islamic Arabia, for instance, water rights were usually established and transferred by force, and in many parts whole tribes exercised collective rights over wells.[164] By enshrining individual rights and spelling these out in detail, Islamic law undoubtedly encouraged private investors.[165] It also gave them the incentive to conserve water due to the benefits that might accrue from this resource.

Throughout the Muslim land, institutions were set up for the purpose of water management and distribution. In Damascus, the management of water was granted to the Sheikhs, that is the trusted and learned, leading figures of the city.[166] In Fes, Morocco, the qwadsiya (workmen devoted to the maintenance of the qadus), that is the system of supply, were placed under the control of the Consul of water.[167] Water disputes in that same city were the prerogative of a special committee composed of representatives from all groups of such users taking counsel from a mufti (learned religious figure).[168] In Valencia, disputes and violations were the prerogative of a special court chosen by the farmers themselves, sitting at The Tribunal of the Waters on Thursdays at the door of the principal mosque (ten centuries later, the same tribunal was still sitting in Valencia, but at the door of the cathedral.)[169] In Iraq, a whole ‘Water Service’ was devoted to the task of supervision and maintenance, and an army of functionaries and other personnel was also involved.[170] The management of the qanat system (under-ground canal) was quite complex. The qanats were scrupulously policed and maintained, and included in their management skilled personnel, and even diving teams.[171]

Under conditions of water scarcity, Islamic society devised a complex system of distribution, in which technical knowledge played a central role. The division of water between several users was assured by a variety of mechanical devices, distributors, or runnels with inlets of a fixed size, and by the allocation of fixed periods of time.[172] Where water is divided by a weir between a number of villages or users, the size of the weir varies according to the share of the water permanently allocated to the different users.[173] During the period of water distribution, shares were defined in terms of days, hours, or minutes, and were allocated to the different districts, villages, fields, or plots of lands watered by the source in question.[174] In the Beni Abbes region of Algeria, in the Sahara, south of Oran, for instance, farmers use a clepsydra to determine the duration of water use for every farmer in the area.[175] This clepsydra times by the minute water use, night and day, throughout the year, taking into account seasonal variations. Each farmer is in turn summoned for his turn, and has to take necessary action to secure most efficient supply of water to his land.[176] In Iran and Egypt, similarly, sand glass and water gate systems measured both time and volume of water used by each farmer. Leo the African speaks of the filling of water clocks when they are empty at the end of the irrigation time.[177] In general, the scarcer the water, the more detailed and complicated the distribution, and the greater the fragmentation of ownership of the water, the more meticulous and elaborate the organisation of its distribution.[178] In the case of qanats, the rotation period could be lengthened in periods of water shortages, and the amount of water per share reduced.[179]

A decisive contribution of Islamic civilisation was to seize on the existing, pre-Islamic systems, and bring them to advanced levels, most of which have survived to our day. The old, decayed systems were repaired, and new networks were constructed.[180] Iraq, for instance, on the eve of the Muslim arrival, suffered from neglect of irrigation, exploitative taxation and crippling wars with the Roman Empire.[181] In southern Iraq, before Islam, the irrigation works were allowed to degenerate, and in the years 627-8, a major agricultural disaster took place, which was followed by devastating floods of the Tigris River which burst its dikes.[182] Soon Muslim rule provided stable government and major hydraulic works were carried out, including drying swamped lands, reclamation of salt marshes, and new irrigation schemes were put in place in the Upper Euphrates region.[183] There was vast reconstruction work of irrigation systems under the viceroy Al-Hajjaj (d. 714).[184] In the Diyala Plains, at least, and probably over a much larger area, the restoration and reconstruction of Sasanian irrigation works took place through the late 8th and early 9th centuries.[185] In Egypt, the work of bringing back into cultivation abandoned lands was begun by Qurra Ibn Sharik in 709-14, and continued throughout most of the 8th and much of the 9th centuries, and in Spain, we learn of the same initiatives.[186] At the same time, land, which had never before been irrigated, or cultivated, or which had been abandoned, was provided with irrigation systems.[187] There is evidence for the extension of irrigated farming from practically every part of the Islamic world in the early centuries of Islam.[188]

As they expanded the surface of irrigated lands, Muslims devised new techniques so as to catch, channel, store and lift the water (through the use of norias (water lifting devices), whilst new ingenious combinations of available devices were put in place.[189] Rainwater was captured in trenches on the sides of hills or as it ran down mountain gorges or into valleys; and surface water was taken from springs, brooks, rivers and oases, whilst underground water was exploited by creating new springs, or digging wells.[190] The Muslims also dammed more rivers, and improved irrigation by systems of branch channels.[191] Engineering expertise remained central to the system, one account explaining how a mountainside near Damascus was tunnelled through to allow the passage of a stream.[192] Distribution of water was also adapted to every soil variety, two hundred and twenty four of these, each with a name,[193] and each with its water requirements. Techniques were also adapted to specific natural conditions.[194] The impact was obviously to make irrigation more economical, and to make lands hitherto unused productive.[195]

Like every dominant aspect of Islamic civilisation, the practical and the scholarly were once more brought together in a vast literature devoted to matters of water, its use, management, storage, and preservation. All Kitab al-Filahat (Books of Agriculture), whether North African, Andalusian; Egyptian, Iraqi, Persian or Yemenite, Bolens says,[196] insist meticulously on the deployment of equipment and on the control of water.[197] Thus, Abu’l Khayr (fl early 12th century) of Seville, the author of a book on farming (Kitab al-Filaha) proposes four ways to collect rain-water, and other artificially obtained waters.[198] He recommends such recovery for growing olive trees, and also explains techniques for maintaining soil moisture.[199] In his treatise, Ibn al-Awwam (fl Seville end of 12th century), speaks at length of the watering process for each crop; in the case of rice, for instance, offering advice for each stage, before planting, and after, and also irrigation and drainage once the crop has grown.[200] Ibn Mammati (d. 1209) implied that in areas where year-long irrigation was available summer crops might be grown after winter crops and income would thereby be doubled.[201] Other treatises deal with the same subject and include Ibn Wafid’s (d.1074) Majmu’ fi’l Filaha (Compodium of Agriculture); Ibn Hajjaj (fl 11th century) Al-Muqni fi’l Filaha (the Satisfactory Book of Agriculture); and Al-Tighnari (12th century): Kitab Zahrat al Bustan (Book of the Flowers of the Garden). The same literature also gives good focus to engineering works aimed at the storage and supply of the resource. Ibn Mammati suggests that the construction of a retaining dam on the Alexandrian canal and the consequent provision of perennial irrigation on lands lying below the dam would achieve an increase in income.[202]

A particular interest is given to the Qanat, that is the underground water system, which conducts water from its source to a distant location.[203] Qanats (subterranean tunnel-wells) are extremely important in the history of irrigation and human settlement in the arid lands of the Old World.[204] In modern times, more than twenty terms are used to identify these horizontal wells; the Arabic word qanatt meaning “lance” or “conduit” is used in Iran, kariz is used in Afghanistan, while in Syria, Palestine, and North Africa fuqara (pronounced foggara) is the most common term.[205] In all of these regions, tunnel-wells are still being constructed in the traditional manner, and many settlements depend on them for irrigation and domestic water.[206] In brief, a qanat consists in reaching for a water source, and transporting water through an under ground canal from its source to the point of distribution over what often are very long distances of 50 miles or so. A series of vertical shafts, resembling but not acting as wells, are constructed along the line of the qanat to allow access for maintenance and removal of spoil.[207] The qanat system allows the sound management and protection of a scarce and precious resource from evaporation and also pollution. It also helps, Guichard notes, to stimulate the prosperity of whole regions that would otherwise remain barren.[208] Oliver Asin in this Historia del nombre Madrid seems to have presented a good case for the Muslims having made it possible to develop what has become the city of Madrid by introducing a sort of qanat system to supply the district with water.[209] Parts of this apparently still exist, and Asin links the actual name Madrid to it.[210] The qanat system has survived to this day in many parts of the world, including in the Algerian Sahara, under the name Fogarras, modern Spain, Central Asia, western China, and on a more limited scale in dry regions of Latin America, where it has a substantial impact on the local farming.[211]

In Iraq, Al-Kharaji (11th century) wrote Inbat al-miyah al-khafiyya (The Extraction of Hidden Waters), describing not only the application of geometry and algebra to hydrology but also the instruments used by master well diggers and qanat builders.[212] The work deals with surveying instruments, methods of detecting sources of water and instructions for the excavation of underground conduits.[213] It devotes various chapters to specific issues, such as notes related to underground water (chap 3); description of mountains and rocks which reveal the presence of water (chap 4); study of grounds with water (chap 5); plants that signal the presence of water (chap 6); description of dry mountains and arid soils (chap 7); on the variety of waters and their tastes (chap 8); how to purify polluted waters (chap 10) etc.[214] There is also an anonymous work, also from Iraq: Kitab al-hawi li l-a’mal al-sultaniyya wa rusum al-diwaniyya (Book Comprising Public Works and Regulations for Official Accounting).[215] Cahen has published the part of this treatise dealing with irrigation.[216] It includes large extracts on norias, gharrafas and other water raising machinery; sections on instruments, techniques of levelling and canals, and their digging, water retention structures, and related subjects.[217]

The Muslim legacy to the West in this field is strong particularly in al Andalus. Witness of such an impact is the considerable Arabic vocabulary in Spanish irrigation (acequia, alberca, arcaduz, noria….) for instance.[218] Another aspect is the prevalence of Muslim techniques, and not just in Spain and Portugal, but also in their former American colonies.[219] In Majorca, there still remain extensive tank irrigation schemes constructed by the Muslims.[220] Remains of Islamic water systems can also be seen in the surviving dams. Many such dams as on the Turia River are now over ten centuries old, and still meet the irrigation needs of Valencia; and they are so effective as to require no addition to the system.[221] There was a similar impact in Sicily, where the study of philology clearly highlights the Arabic etymology of Sicilian vocabulary related to irrigation.[222]

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Land, water, air, fire, forests, sunlight, and other resources are considered common property, not merely of humans but of all living creatures.[224]

Following Muslim rule [Le Strange notes] lands of the realm were measured, records were systematically kept, roads and canals were multiplied or maintained, rivers were banked to prevent floods; Iraq, formerly half desert, was again a garden of Eden; Palestine, recently so rich in sand and stones, was fertile, wealthy and populous.”[225]

Just as with water, the arrival of Islam considerably altered land ownership, and more crucially, land use. Following the conquest of Egypt (639-645), Caliph Omar (Caliph 634-644) rejected the advice of Zobeir to divide the land amongst his followers. ‘Leave it,’ said Omar, ‘in the people’s hands to nurse and to fructify.’[226] The Muslims, Durant notes, could have devastated or confiscated everything, like the Mongols or the Magyars or the raiding Norse; instead they merely taxed.[227] Conquered lands, while forming a part of the public domain, could not be acquired by those who had conquered them, and continued to be occupied and tilled by their former proprietors.[228]

Islam legalised individual ownership of the land in contrast to tribal institutions which made the hima (the land which was kept as a preserve, sacred territory, or land reserved for the exclusive use of a tribe or a tribal chief) common to all members of the tribe.[229] By furthering concepts related to land reclamation and distribution, Islam transformed the Arabs from nomadic people into a civilisation of land owners.[230] Although this Islamic conception of land ownership was connected with the actual possession of the land, it did not preclude the other concept that property is God’s to give, and so is the land, and that people can use and exploit both.[231] Individual ownership of the land was, however, neither absolute nor unconditional, for Islam laid down some regulations, which limited its absolute character.[232] Since the concept of ownership was to encourage people to make use of land, and since land was granted for both individual and communal benefit, the right of ownership would cease to function if the cultivation stopped.[233] Accordingly, both the Prophet and Caliph Omar took back land which had been granted to some of the Companions who were unable to exploit it. Omar took back from Bilal ibn Al-Harith al-Muzni some of the land that the Prophet had granted to him, saying:

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Among the rights which were acknowledged by Islam for the purpose of individual land ownership is the reclamation of waste land, defined as land without any owner, and without any trace of cultivation or development.[235] According to one of the Muslim jurists, Abu Hanifa, ownership only holds if the former owners are unknown, and this ownership through reclamation becomes established only when the reclaimer begins the process of reclaiming it by cultivation or digging it, or surrounding it with walls, but if he ceases to work it, he would only have priority but not ownership, and he stipulates a period of three years as a proof of working.[236] However, Caliph Omar, once more, cancelled the practice of placing a stone or digging a ditch around a piece of land, prohibiting reserving any part of it.[237] The Islamic jurist Al-Shafi’i explains that if the ruler grants a piece of land, or if someone reserves for himself a piece of dead land and prevents anyone from developing it, the ruler has the right to tell such person that if he develops such land, it is his, if not, it will be taken from him and given to another Muslim who would be willing to develop it.[238]

The Islamic legal corpus also gave great incentives to land improvement. One such incentive was in exempting or taxing at only half the normal rate lands planted with permanent crops which had not yet begun to yield, which, no doubt, encouraged investment in tree crops, such as bananas, citrus, mangoes and coconut palms, which ultimately yielded far higher returns than the traditional crops.[239]