This paper examines the role of the private sector in the development of Muslim civilization. For over fourteen centuries, the private sector has remained active in the development of Muslim civilization, although to various degrees. The extent of private sector involvement was directly related to Muslim adherence to the Qur’an doctrine and Sunnah teachings. Merchants were the chief contributors and provided financial support to fight poverty and hunger, to build and operate schools, bimaristans (hospitals), mosques, and other public facilities. The private sector was involved regularly and when necessary in affairs such as support in case of disasters, wars, public service infrastructures, political events, conflict resolution, and others. There were some unsuccessful aspects or aspects with limited involvement of the private sector such as fighting corruption for the ruling authority, supporting housing for the poor, enacting and changing laws that allow accountability and transparency, and others. A proposed idea is presented on how the sector could be institutionalized, enhance its operation, and optimize its role.

Figure 1. Private Sector’s Role in Muslim Civilization Development banner drawn by MidJourney A.I. added here by Jemo (©MidJourney CC BY-NC 4.0)

Muslims established a prosperous and flourishing civilization that spanned over huge geographic areas for more than fourteen centuries and contributed to the development of all legislations, sciences, and technologies while applying the principles of justice, equity, and equality in governance.

The study of Muslim civilization is multifaceted and we may look at it for history, culture, science and engineering, politics and law, economy, medicine, literature, and jurisprudence among other things. However, the private sector’s role in the development of this civilization has not been given the necessary attention, and to date, little has been written about it.

The private sector is the part of an economy that is not controlled or owned by the government including all for-profit or non-profit businesses (companies, industries, trade, productions, dealings, transactions, contracts, selling, buying, and all related organizations and institutions) being small, medium, or large.

In Muslim civilization, the three sectors are the State, the public, and the private sectors. The State includes the House of Treasury including tax collection while the public includes mosques, endowments, major water resources (rivers, lakes, etc.), forests and protected areas, roads, bridges, and others. Both the State and the public sector are administratively under the State. The private sector includes schools, hospitals, housing, commercial markets/centers, trade, farming, and others.

The development and support of the private sector are important due to the role of small and medium enterprises in supporting the strength of the economy. The private sector plays a key role in economic development through participation in economic and social decision-making as a national and moral duty.

It was suggested that civil society (the private sector) can be used to empower competing voices within the Muslim community (and State) and foster mutual accommodation between religious commitment and national values [3].

Since ancient times, the private sector has been a feasible alternative to the public sector and it remains the case today. At present, it is a measurement for developed economies, where it is considered one of the most important elements upon which to build the overall framework for sustainable development [4].

The Islamic Corporation for the Development of the Private Sector (ICD) is a multilateral development financial institution and a subsidiary of the Islamic Development Bank (IDB) Group. Established in 1999, ICD currently has an authorized capital of $4 billion and a membership of 53 countries. The ICD is enhancing economic development by providing a variety of Islamic financial services and products throughout its member countries [5].

This paper aims to explore and review the role of the private sector in Muslim civilization in economic/financial urban State development.

2.1 Definition

The definition of Muslim civilization used in this paper is drawn from the definition of biography [6] which principally means the written history of Muslim people and their life including cultural goods, ideas, traditions, and habits, and the entirety of written literature about them.

2.2 Private Sector and Privatization

Throughout history, Muslim states and their rulers supported the building of the right infrastructures and protected their subjects from exploitation and monopoly. They allowed people to own and manage their properties and work freely without restrictions. They gave their subjects personal incentives to work, produce, and make a profit. Accordingly, in principle privatization is a basic Islamic economic law.

The Islamic perspective of the private sector and privatization is an interesting one; while the acquisition of wealth through legitimate means is permitted, there is the need to drive a middle course between profit maximization, and social and religious responsibility [8].

Moreover, in Islam it is not permissible to allocate a public resource or a public value (from which the public benefit) to one group of people omitting another. Such allocation will lead to harm to others, and such measures raise temptation and problems in society (see hadith [9]).

Ibn Khaldūn in 1377 was the first to envisage the implementation of a privatization policy. He recommended that the State (the caliph) should not interfere in the commercial sector, leaving it to merchants and farmers [10].

Before being a caliph, ‘Uthmān Ibn ‘Affān was a good rich merchant. As his trade flourished and he acquired wealth, he helped Muslim society in many ways; for instance, he bought a water well to enable people to have water supply in times of hardship. He also endowed a whole caravan of grains to the poor during drought and when needed he supplied the Muslim army.

Thus, from these examples, it is apparent that privatization does not mean a monopoly and that Islam does not set or fix prices [11]. However, Islamic practices created quality control and accountability measures such as the Hisba (the department of control and computation) and Muhtasib (the employees who do the control and computation). Control and computation were concerned with quality, quantity, and prices[12].

Especially in the first era of Muslim civilization, Muslim merchants played a major role in spreading Islam in many regions of the world. In communications and dealings, Islam called merchants towards good conduct through commandments that enabled them to set an example for others to follow. Examples of these commandments and instructions include:

3.1 Faith and Belief-Related Concepts

God’s (Allah’s) call to the believers in the Holy Qur’an, “O you who believe,” appears ninety times. If we study the commands directed to Muslim believers, we find that they are concerned with encouraging good deeds/conduct or preventing evil deeds/conduct. The following are examples of such teachings:

3.2 Financial and Economic Transactions and Dealings

There are many clear instructions in the Holy Qur’an and Prophet’s teachings for Muslim financial and economic transactions and dealings including the following:

3.3 Social Dealings and Welfare

In social dealings and matters of welfare, Muslims are instructed to be caring and supportive. For example:

Given the broad scope of the topic, this section contains more general information under different titles. In some cases, the same or similar information is mentioned in more than one section to show the importance and significance of the topic.

4.1 Introducing Islam to the World

Muslim merchants as a major private sector component have played a major role in introducing Islam and the Arab-Islamic civilization to the world since the first century AH. They have contributed to transmitting the message of Islam to many regions in the world including East and South Asia and Africa. Muslim merchants were most knowledgeable in Islam as well as various sciences and represented a good example for the people who engaged with them [58].

4.2 Initiating Commercial Markets and Trade

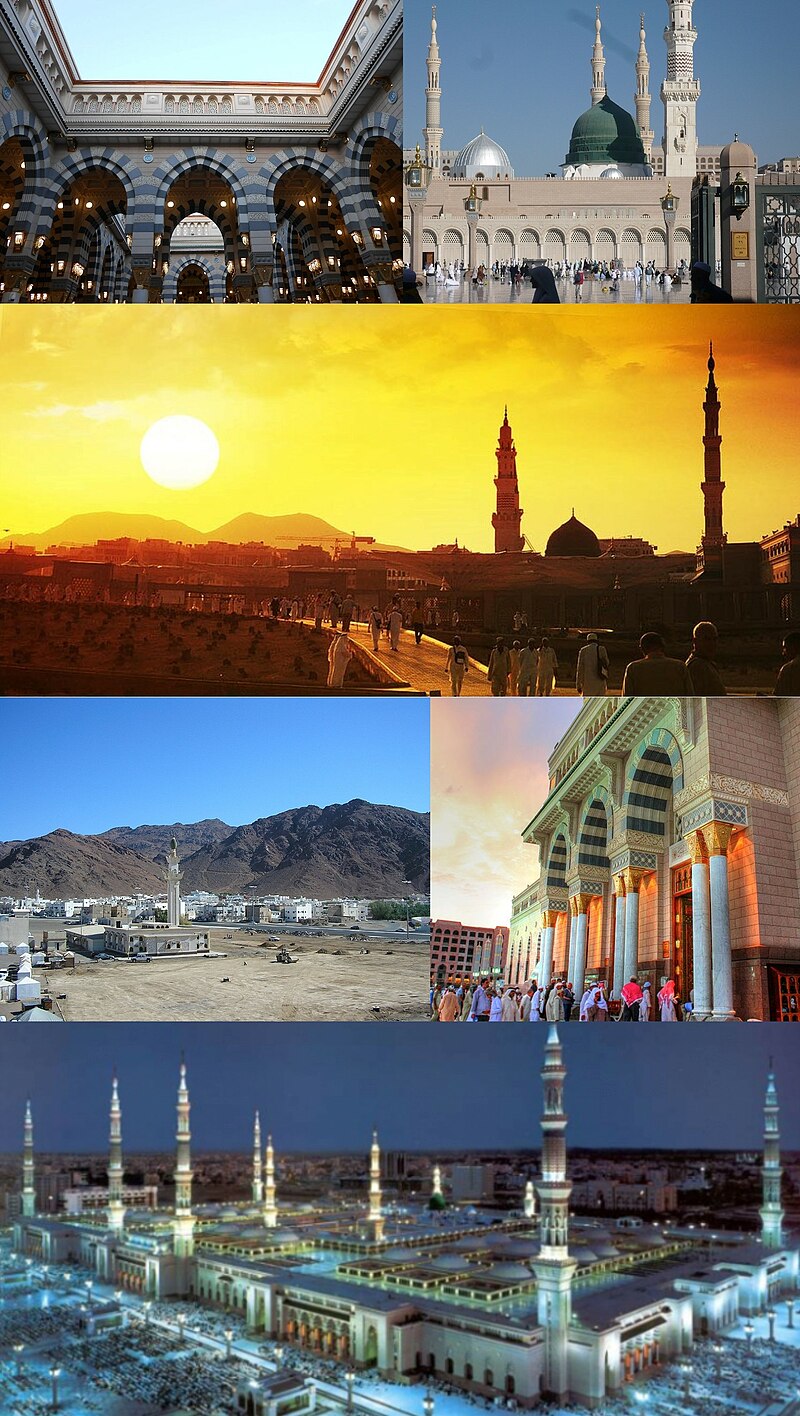

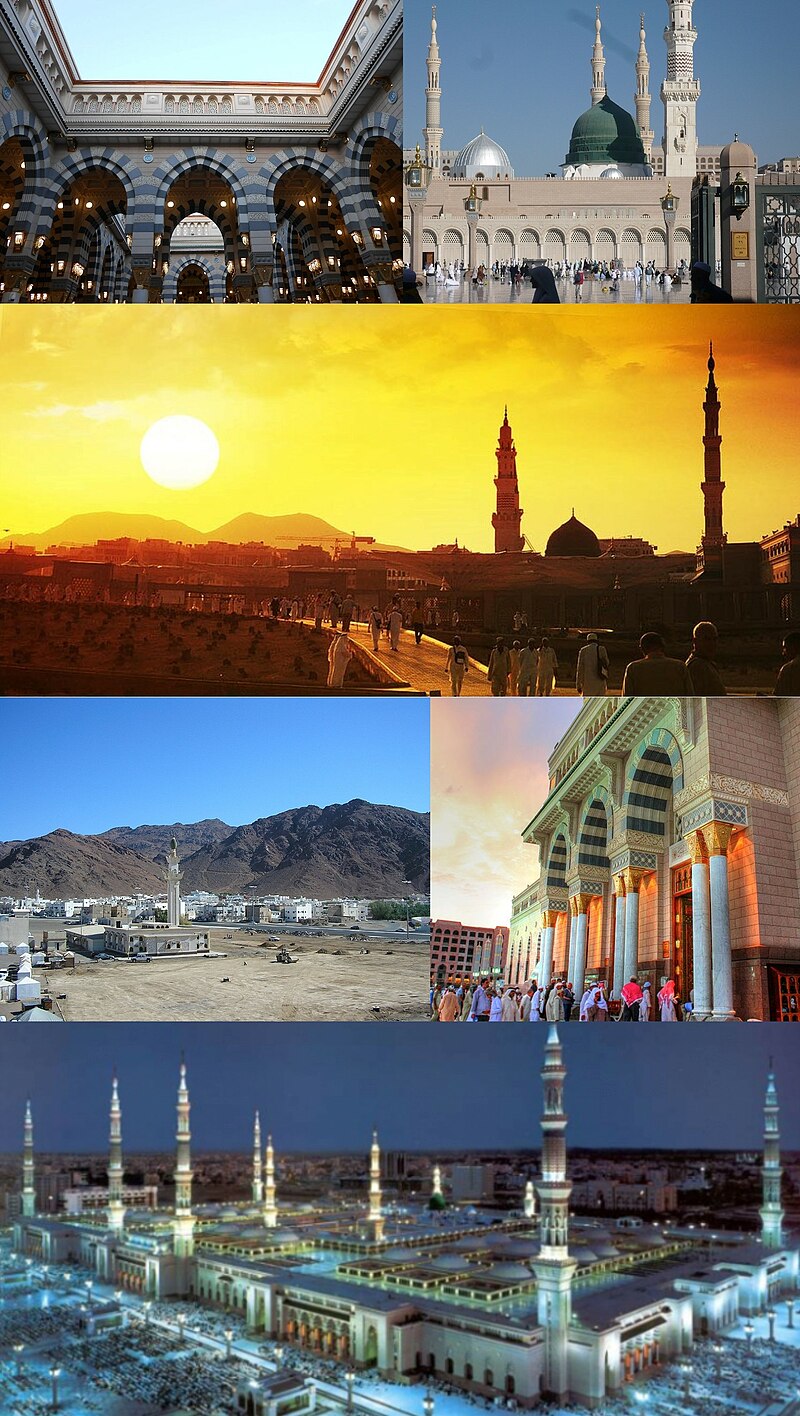

Figure 3. Counterclockwise from top right: Al-Masjid an-Nabawi, Al-Masjid an-Nabawi interior, Medina skyline from Jannat al-Baqīʿ, Quba Mosque, Mount Uhud, Mosque of the Prophet Skyline at Night, Exterior entrance of Masjid an-Nabawi. (Source)

The Prophet (PBUH) strived and worked to establish a special commercial market in Madina and he exempted merchants from paying taxes. This was the first commercial market to be held at the beginning of Islam in the Arabian Peninsula.

There were two types of commercial markets in Islamic cities: private and public. Private markets that were established include the Basra market, which the governor bought from the merchant Abdullah bin Amer bin Kariz from his money and gave to his family; and the Wardan market in Fusṭāṭ (old Cairo), Egypt which was owned by Wardan al-Rumi, the slave of ʿAmr ibn al-ʿᾹṣ. As for Damascus, private commercial markets abounded, and among them were: the Saqala market, which ʿAbd al-Malik ibn Marwān cut off for Sufyān ibn al-Abrad ibn Abi Umama, and the Khalidi market. Public markets, in addition to private markets, also spread in all countries. Among them were: the Hazura market, the Al-Abwa market in Mecca, the Khuzameen market, the slave market, the horse market, and the Mahzur market in Medina. In Iraq, the public markets were found in Kufa, Basra, and Baghdad. The most famous of them were the nursery market, the carabis market, the weapon market, the al-Kala market, the Tuesday market, and the slave market. The cannabis market, the hashish market, and the Wednesday market were famous in Mosul. In Yemen, public markets included the Wolves Market and the Aden Market, the latter considered to be the oldest Arab market. The Tihama Habasha market was also considered to be the largest market. In Bahrain, the Dareen market exported perfume to Mecca and other parts. In Ahvaz too, the Ahvaz market and the Wednesday market remained public markets [59].

There were two types of commercial markets: (1) permanent, such as the city center market, and (2) temporary or seasonal such as the animal market (which was usually held at the end of the week), the annual Hajj-pilgrimage market, and Busra Market in Damascus which was open annually in July for a few weeks. Temporary markets were mostly located in plots/yards at the borders of the city [60]. Also, for each profession, there was a market known by their names such as carpenters, smiths, textiles, poultry, butchers, and others. Some markets were covered or in a closed space and others were in the open without cover [61].

Muslim states have followed the policy of freedom of trade. It has not restricted the transfer of goods between the various counties and cities of the Muslim word, nor has it monopolized the trade of any merchandise or prevented its exchange. There is no doubt that this policy provided some individuals with the opportunity to monopolize some commodities, but their monopoly was mostly local, temporary, and not supported by government privileges. Therefore, it did not have a continuous or comprehensive effect on prices in all parts of the Muslim world, and Muslims, in general, were alienated from these individual monopolies [62].

4.3 Merchants and Civil Society Services

The huge developmental contribution made by merchants to the service of Islamic societies ranged from funding endowments for education (schools, students, and teachers), health institutions, constructing religious buildings such as mosques, caring for the weak groups, the poor, orphans, and unmarried girls.

In the Fatimid era, merchants were very active in contributing to social services; they built public steam baths in Cairo and endowed them free of charge, built schools and supported their operation, and built mosques and bimaristans (hospitals) amongst other things. For example, merchant Nour al-Din Ali bin Muhammad al-Kwaik built one of the largest steam baths in Cairo, and merchant Izz al-Din al-Salami al-Baghdadi built a large school and a house for memorizing the Holy Qur’an in Ras Darb. Al-Rayhan in Damascus and merchant Othman bin Affan Al-Masry built a guest house or corner for spiritualists for Sufis (zāwiyah) and a mosque in the Chinese city of Khansa; he was credited with spreading Islam and Sufism among its people. Also, merchant Muhammad ibn Muhammad al-Kharroubi built the al-Kharubiyya school in Cairo in the eighth century AH / fourteenth century CE and supported it with teachers and essential educational materials [64].

4.4 Enhancing and Supporting Employment

The private sector is a key stakeholder in both urban and economic development, being a major contributor to national income and the principal job creator and employer. The private sector provides around 90% of employment in the developing world (including formal and informal jobs), delivers critical goods and services, and contributes to tax revenues and the efficient flow of capital. Furthermore, it undertakes the majority of future development in urban areas [65].

In early Muslim civilization, the focus was on encouraging agriculture to ensure food security, as well as to secure income for the state from taxes. Accordingly, the demand for agricultural workers (manual labor) was high. With time, trade, all sectors of agriculture, industry, urbanization, jurisprudence, science, medicine, and various services flourished. Consequently, the demand for labor was high. For example, it was reported that during the 8th–11th centuries of Muslim civilization, there were on average 63 unique occupations in agriculture, 697 unique occupations in manufacturing, and 736 unique occupations in service [66]. The proportionality in the numbers of occupations in these sectors varied over time and reflects the changes in the economy.

4.5 Enhancing, Supporting, and Developing Urbanization

Three features of Muslim civilization played an important role in the spreading and continuity of urbanization; these include (1) Waqf (endowments) and their role in preserving and maintaining Islamic civilizational edifices, (2) the intellectual freedom that Islam provided, and (3) the moral aspect of civilization that manifested in Muslims’ protection of Christians [67]. The role of the private sector in using waqf (endowments) will be presented in a separate section (section 4.9).

The goal of urbanization since the beginning of Islam has been to consolidate coexistence between the different groups of society, so once the Prophet (PBUH) settled in Madina, he fraternized between the three groups that constituted Madina: the Aws, the Khazraj, and the Jews [68].

Muslim civilization thrived and flourished through the spread of urbanization. In the year 1200 CE, most of the largest cities in Islamdom — like Baghdad, Basra, Kufa, Damascus, Marrakesh, Cairo, Al-Qirawan, Tunis, Alexandria, and Aleppo — had more than 100,000 residents each. They were highly urban with nice houses, palaces, castles, mosques, and buildings with operational infrastructures [69,70].

With the flourishing of trade in Islamdom, markets and industrial factories became pillars of urbanization. The movement of money and goods became active, crafts and industries flourished, religions and cultures converged, and factions and sects coexisted. Moreover, an endless array of public utilities were organized and established in the form of government departments, scientific institutions, health facilities, and service centers [71].

Muslims erected magnificent buildings and palaces that are still visible in the present day in many places around the world such as Alhambra in Spain and Taj Mahal in India.

Crafts and small industries or factories flourished in Muslim cities including (1) metal industries such as iron, copper, gold, and silver, (2) food industries such as sugar, fruit, and fish drying, marmalades, and grain mills either run by air or water-driven power, (3) textile industries such as cotton, linen, silk, (4) wood making industries such as windows, doors, gates, decorations, (5) Carpets, rugs, straw mats, and prayer rugs and (6) others such as burning oil, salt, marble, soap, paper, pigments, luxury ceramics, medicine, perfumes, glass, sulfur, and precious miniature paintings.

These cities also flourished with scientific/educational institutions and libraries, medical services, charitable institutions, trade, commercial markets and centers, and social life [72].

Long-distance trade, which capitalized on the unique locational advantages of the Middle East and Central Asia, served in Islamdom as a catalyst for economic prosperity and urbanization during the medieval period [73]. Lombard described Muslim cities during this period as a “series of urban islands linked by trade routes [74]. Increasing trade fed the growth and development of the Islamic city, Cairo — situated at the intersection of Red Sea trade routes and overland routes to Sub-Saharan Africa — which was home to palaces, city fortifications, and large mosques [75]. It was stated that the vast size and the importance of merchants in medieval Muslim cities made them important locales for economic, political, and religious life [76].

For long-distance trade, the rich and merchants used to build khans and motels along the roads for travellers such as Noor Eldin Mahmoud who built several motels for travellers to provide security for them and their goods, while protecting them from hard weather [77]. Some of these motels had a section for keeping deposits and money. These motels were used to provide meals and accommodation free of charge. Also, some Muslim women built free-of-charge motels in Damascus [78,79].

The residential areas built by broader families within the Muslim city were characterized by house clusters with dead-end streets that, in a manner that resembles grapes, produced neighborhoods and quarters with little orientation for the stranger. This structure can be explained by the strong emphasis on family and tribe that closes itself off in one compound from other families and tribes [80-82].

Besides being a religious, cultural, educational, political, and social center, mosques in Muslim civilization continuously developed and improved in structure, view, and function. Muslims have mastered the construction of mosques, and apart from being places of worship, they have been a principal reason for spreading Islamic culture. Mosques were for worshipping, learning, and a house for welcoming ambassadors and foreigners. Muslims also mastered the design and construction of beautiful mosque minarets [83].

In addition, Muslim engineers invented many architectural techniques, including domes/shells, columns, arches, and curved structures, muqarnas (merging between two structural objects), mashrabiyas (Protrusion of rooms on the first floor or above), balconies, architectural acoustics, decorations drawn from nature’s objects, embroidery and needle works, dams on rivers, water channels, water wheels, fountains, public water fountains (sabīls), fences, walls around cities with strong notable gates, castles, public gardens, and others [84].

The high urbanization rate and architectural developments in Iraq in the eighth and ninth centuries reflects the power of the society to generate agrarian surpluses. This period was also a high point of culture, scientific scholarship, specialization in both agriculture and industries, as well as trade. Baghdad perhaps would have been able to claim the title of the intellectual capital of the world, which again points to the ample availability of surpluses [85].

Khanqah is a place of worship for seclusion (iʿtikāf) and housing for worshipers. Khanqah seem to have started appearing in Khurasan and Transoxiana in the 10th century as centers of prayers and teaching on various aspects of Islamic law or sharīʿah. It is a large room with a dome (sometimes used as a school), consisting of a praying place, a Sabīl (water fountain), room(s), a kitchen, a library, and sanitation services. Khanqahs have no minarets and does not act as mosques. There is a responsible person, sheikh, assigned to manage each Khanqah. It was renamed Zāwiyah in Syria, Egypt, and Palestine. After it originated in Iran, it began to be established in the year 400 AH in Basra, soon after spreading to Iraq, Syria, Egypt, Jerusalem, and Morocco [86]. It was reported that over 700 Khanaqah were built in Morocco. Khanqah can be built and operated as waqf by rulers as well as by rich people in the society.

Similar to Khanqah in structure and purpose, Al-Ribāṭ are worshipping houses that originated in Tunisia, mostly in border points before Khanqah. Notable ribāṭ include the Al-Minister Ribat built-in 169 AH, Ribat Susa in 206 AH, and Shoutran Ribat in 305 AH [87].

4.6 Private Sector and Building Mosques

Some mosques in Islamic history and civilization were built by order of the caliph or ruler, but most mosques were built by ordinary people (merchants, rich people, nobles) from their own money, seeking God’s (Allah’s) acceptance/approval and the reward of ongoing charity. Usually, these mosques were named after the one who built them. A school/dispensary or a clinic to treat the sick or a room for event gatherings surrounding the mosque would be attached to it. Muslims mastered the construction of mosques in terms of size and shape, domes and minarets, and the material used in building the mosque. The Muslim private sector built many mosques in Muslim and non-Muslim cities. In some cities, a mosque was built in every neighborhood and for every 1000-1500 Muslim inhabitants. Therefore, it would not be possible to comment specifically on the private sector’s role in such matters.

4.7 Private Sector and Community and Humanitarian Services

Community and humanitarian services are a characteristic of the Muslim community. In this regard the Prophet (PBUH) said:

In case when there was no money left in the Muslim treasury, the governor could approach the rich people in the Muslim community and press on them to contribute to support the poor and hungry.

The non-governmental community and humanitarian service in Islam play a major role in caring for orphans, the needy, the disabled, widows, and the elderly, as well as providing aid during disasters and famine. It is mostly done voluntarily by individual Muslims without documentation or mention.

4.8 Revitalizing the Economy through Charitable Work

Figure 4. First pages of the Suleymaniye Kulliye (Complex) deed (waqfiyya) written in 1557. Source: Vakiflar Genel Mudurlugu Arsiv & Nesriyat Mudurlugu Arsivi, N° 52 (Source)

Charities invested in developmental activities promote economic growth and stability through programs that increase access to water supply, sanitation, health, housing, and education.

Guided by their religious belief, Chinese Han Muslims adhere to three principles in charitable work. First; sympathy, compassion, and helping the poor constitute a basic rules for work and life. Second; the distinguishing characteristics and main objectives of Islamic economic and religious activities are sympathy, compassion, and helping the poor. Third; the teachings of charitable works in Islam are clear and specific.

At present, Islamic organizations in various places in the Han region are investing in the establishment of economic institutions with funds from donations and alms of Muslims and financial contributions from the government and individuals. They seek to increase their value so that they can employ them to serve the community in the best and widest way. For example, a doctor started an initiative of buying blood from patients to save the lives of more patients. This initiative invited others to invest funds in establishing vital institutions and projects that upon operation can generate new and additional financial returns [90].

In Indonesia, it was reported that the establishment of Muslim charitable associations signifies an increasingly visible Islamic social activism. Acting as non-state welfare providers, the associations provide “social security” to poor and disadvantaged groups as a means of promoting the public good [91]. An example is the Indonesian charitable clinics that provide free medical help to the poor [92]. These acts certainly benefit the development of the local Islamic economy.

Modernization has contributed to legal reform, management, and the program innovation of charitable organizations in Indonesia which has increased the possibility of the use of a charity for development and social justice. Program innovation included the addition of educational, health, disaster relief, economy, and socio-religious programs, advocacy for victims of evictions, providing research and training grants, supporting anti-corruption programs, and campaigns for environmental conservation [93].

Reports explored progressive models of reproducing economics into some of the infrastructure, practices, and motivations for Islamic charitable giving in London’s East End. Behind large, formal institutions like Islamic Relief and Muslim Aid, there are many other charitable entities, some mobilizing considerable annual donations for infrastructure development projects in London, elsewhere in the UK, and overseas [94].

The Nation of Islam (NOI) in the USA, has a longstanding record of involvement in civic, economic, and political activities outside the strictly religious arena [95]. In some economically deprived areas, they have played a role in providing services that the public institutions have not. It has, for instance, engaged in door-to-door campaigns to raise awareness about local pollution, and patrolled neighborhoods as a community watchdog, especially to stop drug dealing [96].

4.9 Private Sector and Endowments

A careful reading of the history of Muslim civilization throughout the eras indicates that the non-profit charitable waqf (endowments) played a prominent role in the economic, social, cultural, and urban development of Islamic societies. Its effects extended to include most aspects of life such as maintaining the socio-economic balance [97]. It has been noted that the involvement of the government/State in managing waqf made its mission and effect on development decrease [98].

Ibn Baṭṭūṭah reported [99] that the endowments in Damascus were of many types and expenditures due to their large number, including:

In Al-Andalus, endowments supported the establishment and operation of libraries and supplied them with books and scientific references. It was reported that the number of books and scientific references in Granada’s libraries supported by endowments reached two hundred sixty-two thousand [100].

In addition, endowments covered a diverse range of services such as repairing, maintaining, and constructing bridges, maintaining old and building new mosques, providing medical services, sponsoring orphans, foundlings, and the poor, assisting science students, supporting farmers so that they could take the seeds of their land for free, helping small traders with free loans, sponsoring the blind and crippled, and even offering milk to poor mothers.

With time, endowment institutions in the Muslim world became frozen, far from being involved in the country or societal development. The issue of how to link endowment to development is relevant and vitally important. Endowment in some Muslim countries such as Egypt is valued in billions of dollars; however, it is governed by close-minded management that has little if any active involvement in society including development. The size of real estate under management is huge and the activities around it are limited. The real estate management of endowment needs to be diversified to increase its capital and optimize the benefits by expanding investment fields and serving economic development.

Al-Salihiya neighborhood in Damascus had 360 schools built through Islamic endowments [101]. Also, those schools had various running expenditures covered through the endowment institutions.

To modernize the endowment institution within the framework of linking the endowment to development, waqf needs to be transformed into an active financial institution in every sense of the word. The conditions for contributing to development will be set by a council of experts in the field. It is necessary to prepare new special teams to manage endowment institutions and work hard to educate them about the new concept of the endowment.

4.10 Building Ports and Harbors

Al-Maqdisi described the construction of the port of Acre, which was built by his grandfather Abu Bakr Al-Maqdisi for Ibn Tulun (254-270 AH). Al-Maqdisi used thick fig tree wood, laid it on the surface of the water next to the port, sewed it together, and made a great door to the west of the port, then built a stone cover on the sewed woods. Every time he built five pillars, he tied them with great pillars to strengthen the structure. When the wood and stones settled on sand (sea bottom), he left the structure for a whole year for stability assurance. Then he continued building layer by layer, and whenever the building reached the old port wall, he connected the new wall to it. He then erected an arch where boats can enter Acre from the sea from only one point for safety and control [102].

Also, it was reported that an Arab Muslim merchant came and settled on the east African coast of the Red Sea in Massawa, Eritrea in 1349. He built a mosque and two roads/ramps/dyke on the port, and with time he endowed forty houses to maintain them [103].

A similar story was mentioned about a Muslim pilgrim who came and settled in Port Sudan in the ninth century AD and built a coral-choked port called Souakin. This old port was demolished in 1905 to build a new port to adopt for larger oil tankers and oil export [104].

4.11 Solidarity and Relief

Solidarity in Islam is rooted in the pillars and characteristics of Muslim society. Fasting makes all Muslims feel hungry and thirsty; group prayers in mosques bring together Muslims to know about each other’s affairs and support when needed; and Zakat also enables Muslims to cover the needs of the poor, the needy, and the wayfarer.

To minimize poverty and hunger, and in order to encourage care for neighbors, the Prophet (PBUH) said: He who sleeps full and his neighbor is hungry by his side and he knows it does not believe in me [105]. He (PBUH) also praised a group of Muslims who, when they had problems with food provision, they collect all the food they had and put it in one jar, distributing it equally to every member of the group [106].

Besides obligated charity (zakat), historically there has been a broad avenue through which Muslims contributed to helping others publicly in order to minimize poverty, hunger, and need. For example, it was narrated that Imam Al-Layth bin Sa’d’s income reached about a thousand dinars every day, yet no zakat was due from him because he give it all out in charity to the needy for the sake of Allah (SWT)[107].

Moreover, in Islam, it is customary that those who die have the right to bequeath their money (not exceeding one-third) to the poor and needy or to build a mosque or school or something else as an ongoing charity for the sake of Allah (SWT)[108]. Similarly, there are Al-Ariyah (financial or materialistic lending to the needy without any return) which can be given, as well as meat distribution to the needy on many occasions.

The Prophet (PBUH) sent money to the poor inhabitants of Mecca when they suffered from hunger [109].

In a time of distress before being appointed as Caliph, ‘Uthmān Ibn ‘Affān bought the well of Romah and endowed it for people to drink from, a well which still runs until the present time[110]. Likewise, at a time of drought and lack of grain, a convoy of one thousand camels of grain, oil, and other foodstuff arrived for ‘Uthmān, but he refused to sell it to the merchants of Mecca and donated it to be distributed to the poor [111].

There are hundreds of stories and cases about solidarity and relief during the Rashidun caliphate and others who followed them. Although it is not possible to list them all here, you can refer to this source for better and detailed knowledge of them [112].

4.12 Private Sector Involvement in Food Provisions

The provision of free food by the private sector began in Muslim society with the brotherhoods, a Sufi system that was found outside the scope of the mosque in what was called the zāwiyah, the ribāṭ, or the hospice [113]. This soon changed to guesthouses [114], offering an immediate means of feeding the poor. Examples of these guesthouses include Dar Al-Aldiyafeh in Turkey and the Takiyeht in Palestine in which food is handed out, free of charge, to specific groups and individuals. The Ottoman Public Kitchens (or guest houses/ hospices) were constructed throughout the Ottoman territories, from the fourteenth century to the nineteenth. An investigation of these kitchens reveals a nexus of patronage, charity, and hospitality [115]. In Hebron, Palestine, Al-Ibrahimiyah Takiyeht (or guest house) named after Prophet Ibrahim was founded in 1279 and since its establishment, it has offered food to poor individuals and families free of charge three times a day. Upon entering the guest house, no questions are asked – you receive a warm welcome and fine hospitality. At the guest house, you either sit and eat or take away the food. Al-Ibrahimiyah Takiyeht is supported by the Islamic Endowment Funds in Palestine and outside. It was estimated that the Takiyeht serves between four and thirteen thousand meals daily or 289 thousand meals in the holy month of Ramadan [116,117]. In most cities in Palestine Takiyehts are open every day in the holy month of Ramadan offering complete meals to the poor. Travellers visiting the city also benefit as they are able to eat at the Takiyehts or the guest houses, establishing a long-standing tradition of hospitality.

4.13 Private Sector’s Role in Conflict Resolution

Among the forms of the private sector is its involvement is what was known – and can still be found presently in Egypt and several Arab countries – as the hostel system, customary councils, and Arab councils for settling disputes without the intervention of the state or judiciary. For the public in Egypt, it represents a form of social solidarity, where there is an individual who needs a large amount at once, so a group of individuals (often amounting to ten) pay a monthly amount, and every month the whole amount is taken by an individual, then the next month another individual and so on, and priority is given to the neediest. It is noticeable that many economic projects started in this way in Egypt. For centuries in Palestine, big families – sometimes consisting of a few thousand members – form a family council to resolve any misunderstandings or conflicts within or outside of the family, to provide economic support to the poor within the family, and to take responsibility for accidents of any nature facing family members and others. It is worth noting that whatever the family council decides on in any matter is fully implemented by all members of the broader family. This system is based on solidarity, common interests, trust, and social bonds.

4.14 Private Sector and Political Events

Arab and Islamic societies in the past enjoyed the existence of forms of social institutions that played important roles in achieving a balance between the people and the rulers, the most prominent of which are [118]:

It was reported that the general public in Iraqi society during the Abbasid era had a major role in the course of political events in addition to the economic aspects [119]. Traders and craftsmen, by being among the public in Islamic cities, have played an important role in public life, contributing to public wealth, joining religious associates and groups, celebrations, and public processions during seasons and feasts. Moreover, they helped during the strife between Al-Amin and Al-Mamun, and they stood firm in defending Baghdad against the armies of Al-Mamun in the year 197 AH [120, 121].

4.15 Private Sector and Trade

The role of Muslim merchants in trade exchange between the countries of great Arabic Morocco – Al-Magrib Al-Arabi Al-Kabir – and West Sudan indicate that trans-Saharan trade was, although associated with great risks and dangers, at its height during the third to the fifth century (AH), especially in gold and salt. Accordingly, trading centers were established along the trading path. The area was vibrant with different traditions and cultures. It is important to note that this trade route passes through three climatic zones which range from the temperate/moderate in the Mediterranean basin to the dry climate in the Sahara, to the subtropical climate in West Africa. Archaeology indicated that there were two roads for horse-drawn carriages – one in the north, and one in the south of Sahara [122].

In 100 AH, Abdallah Ibn Ja’far, an Arab Muslim from Basra, excavated an earthen water canal from the western side of the Al-Furat river and flowed into Shat Al-Arab in the eastern parts of Basra called upon him. On the sides of the canal, he built a market that became an active commercial center. Several similar canals and markets were established after Ibn Jafar’s canal and market.

The Muslims’ conquest of North Africa and their settlement there leading to the spread of Islam in the area boosted trade, making it the largest of its time [123]. Furthermore, the spread of Islam from North Africa to the south, to southern Egypt and West Sudan took a much longer time (during the second century AH), and subsequently led to the revitalization of the trade between the northern and the southern areas [124].

4.16 The Role of the Private Sector in Promoting Good Governance and Fighting Corruption

Good Muslims need to come out in their daily life activities to establish justice in the society, enjoin what is right, forbid what is wrong, and return people being individuals or groups to Allah (SWT) and his sharia using the best manners and approaches.

There are rich practices in the Islamic heritage of high moral standards, ethics, values and norms of behavior, which govern Muslim’s personal, professional and business life. These standards, ethics and values including those related to promoting good governance and fighting corruption are rooted in Islamic Sharia that prevailed since the start of Islam. The following cases are an example of such practices:

4.17 The Role of the Private Sector in Economic Resilience During War

In Yemen, since the war and conflict which started in 2015, a large number of casualties have occurred and a big portion of the infrastructure has been destroyed, as well as economic and social services being obstructed and disabled. The private sector contributes about 70% of Yemeni gross domestic product. About 39% of Yemeni companies closed and the rest (90% of service providers) suffered from size reduction and a decrease in their production [130]. Over the last five years of conflict, the private sector has shown impressive resilience despite numerous internal and external challenges.

Both the food and health sectors have experienced growth and are contributing significantly to the humanitarian efforts in the country. There is an interesting growth found in the number of women business owners over the years from 1.7% of female-owned businesses established between 1975-1999 to 11.7% in 2016 which presents an opportunity to support female businesses’ growth. To strengthen the capacity of institutions to provide support and advice to businesses, the Yemeni Private Sector Cluster was formed. It is a neutral body of major representative bodies of the Yemeni Private Sector including the Chambers of Commerce from all regions of the country and key business management associations, formulated to advocate for and find solutions for policy-level macroeconomic issues affecting the private sector of the country [131].

4.18 Banking, Financing Benefits, and Services

Merchants in the Abbasid era had agents and clients assigned in special commercial centers (such as Oown road in Baghdad and Ashab Al Einah in Basra). These agents and clients had the duties of (1) collecting the merchants’ revenues obtained in the market or (2) paying the debts of those who worked for them, and (3) arranging to borrow or provide loans. Accordingly, they wrote bills of exchange, and the Sukuk (bonds and debentures) became popular in the city of Basra. These bills of exchange and Sukuk were sealed with red wax or clay for the security of content [132-134].

Financial services grew during the eighth and ninth centuries in Iraq. There were numerous money changers, pawnbrokers, and merchant-financiers, and the latter employed sophisticated instruments, including innovating the money transfer system and bills of exchange and letters of credit [135]. In addition, financial markets in the towns and suburbs developed in a much more favorable way, linking them to systems applied in urban markets and long-distance commodity trade.

Financing public benefits and services including Hajj and Umrah is one of the important methods of Islamic banking/financing developed at the global level under the concept of Murabaha, which is still under consideration and debate among scholars, jurists, and researchers. Although Muslim Jurists have allowed the Hajj and Umrah banking service, some still argue that there is no need for such services since Hajj and Umrah in Islam are not obligatory for those who cannot afford them. Details and analysis have been reported of the economic and social impact of such services on the institution itself and the individual beneficiary, with an analytical study of the Hajj and Umrah contract items through which the service took place (the case of the Jordan Islamic Bank as a model) [136].

4.19 Scientific Renaissance and its Applications

It was stated that Muslims digested the sciences of the ancients and then set out to study, research, and develop them, so their rapid scientific renaissance and occupation of the leading position in this field was a miraculous matter [137, 138].

Muslims excelled in all sciences and related professions and fields. They worked on existing sciences and further developed them such as medicine, physics, pharmacology, geography, optics, astronomy, engineering, urbanization, history, arts and literature, plants and animals, philosophy, as well as translation. Muslims also developed/innovated new sciences such as chemistry, geology, mysticism, pharmacology, algebra, mechanics, sociology, and language. Many detailed books were written on these subject matters, although this section will not be able to cover them all. For more information, the reader can refer to the following literature [139-147].

Among the important inventions, Muslims invented the marine compass which enabled them to revitalize and master the sea trade [148].

4.20 Establishment and Development of Private Schools and Colleges

The establishment of private schools, independent of mosques, started at the beginning of the fourth century AH in Nishapur, Khurasan Province. During this period, the Al-Bayhaqi School, the Saadiya School, the Al-Istrabadi School, the Asfrabini School, and the Ibn Sabktekin School were established. A remarkable feature of these schools is that funds and buildings were allotted (endowed) at the time of establishment (and later by the school founders, merchants, and nobles) for their continuation and development. These schools increased in number and quality until they reached 38 schools in Baghdad when the Mongols conquered [149].

Scholars and jurists used to collect their books and manuscripts and put them in a school under the tutelage of a clerk who would preserve them and facilitate their use for whoever wanted them without taking them out of the school. The expenses of these schools were insured through waqf. ِ Also, the schools were used as hostels for visitors from outside. One such school is that of Ibn Hayyan al-Tamimi who died in 354 AH [150].

Schools erected in Muslim civilization had a distinctive architectural character, consisting of one, two, or more iwans. The number of iwans (Alawawin) had nothing to do with the type or quality of education used in the school. Examples of these are Al-Mansuriyya School in Cairo, which consists of one iwan and exists to this day, and the Al-Mustansiriya School in Baghdad which consists of two iwans [151].

Historical sources indicate that there were large science circles (Zawaya and Halaqat) in many mosques of the Abbasid state. In every mosque, there was a library as it was the custom of scholars to endow their books in the library of the mosque. The Al-Mansur Mosque in Baghdad, the oldest mosque in the city, was one of the most famous educational centers of the era. In 210 AH there were 700 scholars and teachers and 11 thousand students in Al-Basra [152,153].

Medicine was initially taught in mosques such as Al-Azhar Mosque in Cairo and private medical schools such as Al-Dakhwaniyah School and Al-Lboudi School in Damascus and the Patkin School in Basra, as well as in bimaristans such as Bimaristan Al-Addi in Baghdad and bimaristan Al-Mustansir in Makkah [154].

It is worth mentioning that Islamic and educational institutions, through waqf (endowment) or direct contributions, have greatly contributed to stimulating cultural activity in Islamic cities by enabling students and scholars to seek knowledge by building libraries and providing housing and financial support for people.

The Messenger (PBUH) was the first to build mosques, and his mosque was built in the middle of the city due to a large number of activities, services, and functions that were performed in it to serve the general population [155]. The number of mosques in Basra in the third century AH reached seven thousand [156], while in Cordoba in the fourth century AH the number of mosques reached 490 [157]. After that, congregational mosques were formed, bringing together the mosque for prayer, a house to accommodate Sufis, dervishes, and the poor, a corner for people to gather for iʿtikāf, a school for teaching religion and various sciences, as well as a library.

The schools had endowments that greatly impacted their development, continuity, and expansion, as well as supporting teachers and students [158]. Most of the founders of schools then endowed books on various types of science as well as arts and religion. The number of schools has increased drastically [159], and it has been reported that the number of Islamic schools in Delhi, India has reached a thousand [160].

Another remarkable feature is that commercial caravans, either by land or sea, remained a safe option for students, writers, and scholars to travel on their mission trips and seek or spread knowledge. These students and scholars used to hold sessions of lectures and talks in the caravan while travelling [161].

4.21 The Establishment and Financing of Bimaristans or “Maristans”

The establishment, development, and financing of bimaristan (a hospital in the historic Islamic world, also known as dar al-Shifa – a healing house – or simply maristan) in Islamdom is another field that was mostly supported by the Muslim private sector, the nobles and rich. Bimaristans used to provide free treatment services and medicine for all diseases (physical and psychological), and food to patients as well as their visitors including family members [162]. This establishment led to the development of the fields of medical sciences, chemistry, physics, and botany [163]. For example, the Bimaristan of Qalawoun in Cairo contained separate divisions for various diseases, including surgery, optics, others for convalescents, analysis laboratories, a pharmacy, outpatient clinics, kitchens, bathrooms, a library, a mosque for prayer, a lecture hall, and places for those afflicted with mental illnesses including views such as gardens and fountains that pleased the eye. In addition, every patient was given a sum of money upon his release – after his recovery – so that he would not have to work to earn his living immediately after leaving it [164].

In addition to fixed bimaristans built in cities, there were mobile bimaristans that covered rural areas. The mobile bimaristans were formed in a caravan of camels (up to forty camels) and with the caravan would be a group of doctors equipped with medical tools and medicines [165].

In some cases, bimaristans were attached to farms of medicinal herbs allocated for the use of doctors in treating patients [166].

Rufaida Al-Aslamiyah or Rufaida bint Saad was a known surgeon nurse before the beginning of Islam and continued with the start of Islam, becoming a companion of the prophet (PBUH). The case of Rufaida indicates that Muslim nurse women from the early days of Islam were permitted/allowed to treat Muslim men [167]. Rufaida treated patients free of charge.

Bimaristans not only facilitated patients to have access to medical treatment but also provided them with a peaceful environment to be treated and recover.

4.22 Public and Private Sector: Collaborative Practice

The private sector, including individual workers as well as all for-profit or non-profit businesses, is the largest user or reservoir for the working/employment force in a country or state and it could support the public sector.

Market Establishment: Muslims took care in choosing the city center and set a large square in it as a suitable location for the establishment of commercial markets, as it represented one of the main centers of public life in the city after the mosque and the ruler’s house. Markets were established as joint public and private sectors: the government provided the land and merchants were involved in market infrastructure. As a tradition, the mosques were named after those who built them such as Al-Khashabeen (carpenters) Mosque, Al-Ramahin (smith and spears) Mosque, and Al-Saffarin (copper shops) Mosque in Damascus [168, 169].

Enhancing, Supporting, and Developing Infrastructures: The Fatimid caliphs in Egypt continued to oblige the general public in Cairo “to light lamps in the rest of the country on all shops, doorways, shops, and one or two-way streets and roads” so they competed in doing that. People in Cairo and throughout Egypt spent all night buying and selling, and also increasing the use of candles. In addition to the legal taxes such as zakat, kharāj and others, there was a tax collected from shops and craftsmen at the beginning of each month called Makous. This tax was used to maintain and develop public and infrastructure projects, such as building bridges, digging water channels, building hospitals, schools, and others. The Makous tax was not continuous or fixed in amount but a variable tax set by the governor as and when needed [170].

4.23 Disaster Management and the Private Sector

Disasters such as the plague hit Muslim nations several times in history; the plague of ‘Amwas in the time of Caliph ‘Umar Ibn Al-Khaṭṭāb in the year 8 AH during which twenty to thirty thousand Muslims died [171]; the plague Al-Jaref of Basra in 69 AH [172]; the plague of Baghdad after the Mongol conquest in 569 AH [173]; the greatest plague which hit Syria during the Mamluks in 759 AH [174], and many other cases. As a result of these plagues, a demographic change occurred as the number of religious leaders died which led to an authority vacuum, and labor and farmers decreased. Consequently agricultural and animal products and crops decreased, all of which resulted in a severe increase in product prices that worsened the economic conditions. During plagues, the Muslim rich and nobles contributed to building and managing bimaristans. Also, to minimize the spread of the plague, Muslims practised the quick burying of the dead, and for this purpose, they established what was called warehouses (cleaning houses) for the dead [175].

During disasters, waqf continues to remain one of the methods of social solidarity within the Muslim world.

4.24 Enhancing, Supporting, and Developing Economic Development

Islamic principles that helped in economic development and growth include: (1) Islam’s allowing of individual ownership, which helped in the initiation of free trade, free enterprise, and other economic spheres, (2) economic freedom, limited to what is permitted according to Islamic law, and (3) achieving profit within limits.

4.25 Trade’s Role in Enriching Economic Development

The role of trade in enriching economic development in the second Abbasid era including physical and human capital, and the private enterprises of various parties is well detailed [176]. Baghdad was the greatest trading center during the Abbasid era [177]. In Al-Yaʿqūbī’s [178,179] description of the Baghdad markets, there were known streets for every trade and merchants, and rows in those streets and stalls, and no people mixed with other trading people, nor trade with trade, and no merchandise was sold with another, and the owners of professions from the most common industries did not mix with others. These markets had the advantage of having all brands of the same merchandise on the same street; however, a disadvantage was that consumers had to go from one street to another to seek their various needs.

It was stated that in Iraq in the early Islamic period, there was relatively unrestricted functioning of markets for goods, labor, and capital. This stimulated market exchange, associated with growing monetization of the economy especially in the towns, but also in the countryside. Besides the land held and exchanged by peasants and minor nobles, the land was also acquired by the new Arab Muslim elites, partly through sale (land sellers were called dahhaqin)[180].

4.26 Enhancing Water Supply

The well of Rumah in Al-Atiq in Medina was bought by Caliph ‘Uthmān ibn ‘Affān (23-35 AH/644-656 AD) and made available as a charity for the people [181].

To enhance water supply for agriculture, landowners excavated wells and ʿuyūn (running springs), and used an underground channel to bring water from a distant aquifer (qanāt) [182, 183].

It was reported that the systems of the hydraulic water supplies created by Arab Muslim citizens for Andalusian cities, castles, and their agricultural areas consisted mainly of aljubes (large water cisterns) which were supplied with the rainwater collected from the yards of these cities. Ceramic pipes and manholes (barrier chambers) or water channels or irrigation ditches were used to connect the cistern and the farms and houses [184].

During the Abbasid period, the Aramaic people were characterized by manufacturing and constructing pottery pipes for transporting water to huge, long distances over difficult terrain for irrigation and water supply [185].

Muslims in the third century (about 950 CE) were the first to introduce water networks/systems using water pipes made of lead or zinc into homes, bathrooms, and mosques. The book “Industries of the Arabs” included drawings and maps of water networks in some Islamic capitals [186, 187].

The engineer Al-Jazarī designed for the first time in history water-raising machinery powered by water and gravity and simulated the principle of balance (windmills and waterwheels, steel mill, bridge mill, double-twin acting principle water pumps, camshaft, crankshaft, and crank-slider) aimed at bringing water supply directly to local people in cities and enhancing irrigation to improve the farming capacity [188,189]. By 950 CE waterpower using a waterwheel was used in Baghdad not only in the water supply but also in industrial processing. This water-lifting practice expanded west to Syria, Egypt, North Africa, and eventually to Muslim Spain [190].

Since early Muslim civilization, scientists actively devised groundwater (they called it hidden waters). Devising or discovering the location of groundwater was based on field experiences, sense, imagination, and wisdom. The depth of groundwater and its proximity to the surface of the earth was located by scientists and experts using (1) soil smell, (2) the smell of plants in the surrounding area, and (3) the movement of a specific animal found in the area [191, 192]. Scholars called their devising knowledge ‘the science of the countryside’ [193].

All over Muslim civilization, public water fountains (called sabīl water) were set up and constructed mostly by private citizens to provide drinking water for the public in the streets [194, 195]. The sabīl water fountain was usually named after the one who built it.

Arab Muslims in Andalusia proved that they were the masters of water and deserved to be described as “protectors of the water civilization”. They built public baths all along Spanish cities and villages to be used by men, women, and children for cleanliness and purity [196].

The work of Muslim scientists such as al-Kindī, Qusṭā ibn Lūqā, al-Rāzī, Ibn Al-Jazzār, al-Tamimī, and Ibn al-Nafīs covered a number of subjects related to pollution such as air pollution, water pollution, soil contamination, municipal solid waste mishandling, and environmental impact assessments of certain localities [197].

Several Muslim scientists pioneered water purification including boiling, filtering, cooling, distillation, sun radiation, and the use of silver [198-208].

One important lesson to learn is that history is not only memories, stories to tell, or a record of facts and events; rather, it is a treasure full of wisdom, lessons and experiences to help us to think about and understand how Muslim civilization developed and how Muslims solved their problems in particular periods of time.

The role of the private sector in Muslim civilization is replete with achievements that are considered examples for people in the future. Throughout history and Muslim civilization, we can observe that the private sector played a major role in fighting poverty and helping the poor in a range of ways, as well as building mosques, schools, and hospitals.

Some aspects were not successful, such as fighting the corruption of the ruling authority, supporting housing for the poor, enacting and changing laws that allow accountability and transparency, and others.

The private sector’s role in the development of Muslim civilization was based on individual Muslim involvement and initiative which is a unique Islamic characteristic, as well as zakat and waqf (endowment). A suggested model for the future would be to create/establish a specialized institution “Attaa Al-Khair” (means giving good) similar to waqf in legal status to (1) strengthen individual Muslim education and knowledge of Islamic Sharia using all media sources and education tracks in order to deepen his faith and drive for good and righteous deeds, (2) study Muslim society’s timely needs such as poverty, housing, education, public health, public awareness and awakening, and others in order to direct individual Muslims to fulfil those needs and promote such projects, and (3) enabling the charitable process by first detailing surveyed society’s needs in fully implementable plans/projects with finances (detailed cost estimates) and code them with financial levels as from low to high financial needs and funding and by second allowing various tracks of implementation (by the funder himself, the institution itself, or a third party). This institution would then publish these projects by various means to the public for those who might be interested in giving. Rich, noble, and knowledgeable people in Muslim societies need to be involved and active in such institutions.

The author wishes to thank helpful colleagues whose names remain anonymous. Thanks are due to Miss Fatima Sharif for her assistance and effort in copy-editing the manuscript.

[1] Monica M. R., (2020). Introduction: Historicism, Modernity and Religion in Islamic Modernism and the Re-Enchantment of the Sacred in the Age of History. P. 12. Published by Edinburgh University Press. (2020). Available from: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.3366/j.ctv182jr7v.4.

[2] Al-Dali, Ali, (1972). Geniuses of Islamic Civilization, Republic Book No. 36. Palestine Picture Book Library. P.6-7.

[3] Emon, A., (2006). Conceiving Islamic Law in a Pluralist Society: History, Politics and Multicultural Jurisprudence. Singapore Journal of Legal Studies [2006] 331–355

[4] Amri, A., and Qurush, M., (2016). The business environment in the Arab countries and the role of the private sector in bringing about sustainable development. A paper presented at the Second International Conference on the requirements to achieve economic take-off in the oil-producing countries in light of the fuel prices have fall down. Université Akli Mohand Oulhadj Bouira, Algir, Nov. 29-30, 2016.

[5] AiGlobal Media, (2021). Private Sector Investment in Islamic Countries. Found in: Private Sector Investment in Islamic Countries – AI Global Media Ltd. Accessed November 2021.

[6] Biography. Available from: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/biography. Accessed January 2022.

[7] Muslim Population by Country 2021. Available from: https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/muslim-population-by-country. Accessed January 2022.

[8] Ariff, M., (1991. Islam and the Economic Development of Southeast Asia. Published by Inst of Southeast Asian Studies. Pp. 1-3.

[9] Sunan Abi Dawood: The Book of the Principality, Chapter on the Feud of the Two Lands, No. 3070

[10] Ibn Khaldūn, and Franz Rosenthal. 1967. The Muqaddimah: an introduction to history. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

[11] Narrated by Abu Dawud, Book: Allegiance, Chapter: On Pricing, No. 3450, and Narrated by Ibn Majah, Book: Trade, Chapter: Who Hates to Be Priced, No. 220.

[12] Fazlun M Khalid, (2002).Islam and the Environment. In the Islamic Foundation for Ecology and Environmental, Sciences, Birmingham, UK. In Encyclopedia of Global Environmental Change, Volume 5, Social and economic dimensions of global environmental change, pp 332–339.

[13] Haddad M. (2012). An Islamic perspective on food security management. Water Policy Journal Volume 14 (2012), p. 124

[14] Listed in Riyad As-Salihin, Hadeeth No.1379.

[15] Listed in Riyad as-Salihin Hadeeth No.1788.

[16] Al-Albani Al-Adab Al-Mufrad 336.

[17] Sahih Muslim 3000a

[18] Riyad as-Salihin 1721.

[19] Narrated by Abdullah bin Amr on the authority of Al-Albani in Al-Silsilah As-Sahihah, page or number 792

[20] Narrated by Al-Nawas bin Samaan Al-Ansari on the authority of Al-Albani in Takhreej Mishkat Al-Masbah, page or number 3624

[21] Sahih al-Bukhari 459.

[22] ibid, Haddad, M., (2012), pp. 121–135.

[23] Ibn Shiba al-Numairi, History of the City, vol. 1, p. 98; Al-Tabari, Al-Muntakhab, p. 109.

[24] Mishkat al-Masabih 2892

[25] Mishkat al-Masabih 2896

[26] Mishkat al-Masabih 2895

[27] Musnad Ahmad 246

[28] Riyad as-Salihin 1615

[29] Mishkat al-Masabih 2807

[30] Glossary of Financial Terms، Institute of Islamic Banking and Insurance

Available from: https://www.islamic-banking.com/glossary_G.aspx. Accessed March 2022.

[31] Sunan Abi Dawud 3460

[32] Sunan an-Nasa’i 4513

[33] Mishkat al-Masabih 2936

[34] Sahih al-Bukhari 2236

[35] Sunan an-Nasa’i 4463

[36] Sunan Ibn Majah 2146

[37] Sunan Ibn Majah 2355

[38] Jami` at-Tirmidhi 1208

[39] An-Nawawi, Hadith No. 35, and No.40

[40] Riyad as-Salihin 1372.

[41] Riyad as-Salihin 793.

[42] Sunan an-Nasa’i 4693

[43] Narrated by Al-mustadrak in Sahih Muslim and Sahih Al-Bukhari.

[44] Mishkat al-Masabih 2910.

[45] Jami` at-Tirmidhi 1315

[46] Mishkat al-Masabih 2796 and 2797.

[47] Jami` at-Tirmidhi 1210

[48] Mishkat al-Masabih 2933

[49] Sunan an-Nasa’i 4506

[50] Sunan al-Tirmidhi, book of sales, the chapter on merchants and how the Prophet (PBUH) named them No. 1209.

[51] Sahih Muslim, Book 10: Transactions (Kitab Al-Buyu’)

[52] Riyad as-Salihin No. 199 – The Book of Miscellany.

[53] Jami` at-Tirmidhi 2090

[54] Sahih Al-Bukhari 1476

[55] Jami` at-Tirmidhi 1298

[56] narrated by Al-Moselly No. 6830

[57] Sunan Ibn Majah 58

[58] Al-Nabahani, I., (1990). Merchants Reference to the Ethics of Good People. Al-Jaffan and Al-Jabi Publishing, Cyprus. P.14.

[59] Markets in the Rashidoun and Umayyads Ers.Available from: http://al-hakawati.net/Art/ArtDetails/1465/. Accessed: March 2022.

[60] Sauvagea, Jan (1936). Damascus, the Levant, a historical overview since antiquity in the modern era, the Catholic Press, Beirut 60-56, 48-43, 1936

[61] Ibn Jubayr, Abu al-Hasan Muhammad ibn Ahmad 1981). The Journey of Ibn Jubayr, Lebanese Book House, Beirut (d. T.), Vol. 2, pp. 188-189.

[62] Agriculture in the Umayyad’s Era. Available from: https://www.islamstory.com/ar/artical/20159. Accessed April 2022.

[63]Learn about the role of merchants in the civilization of Isla. Found in: https://islamonline.net. Accessed march 2022.

[64] Karmic. What do you know about the most famous businessmen of the Islamic era?. Available from: https://www.aljazeera.net/midan/intellect/history/2019/10/17/. Accessed March 2022.

[65] Venables, T. (2015). Making cities work for development (IGC Growth Brief 2.) London: International Growth Centre. P.5.

[66] Shatzmiller, Maya (1994), Labour in the Medieval Islamic World, Brill Publishers, pp.169-170.

[67] Haddad, M., (2021). Islam’s Influences on People’s Pro-Environmental Practices. Published by in Muslim Heritage, Nov.6, 2021. Available from: Pro-Environmental Practices in Muslim Civilization – Muslim HeritageMuslim Heritage. Accessed April 2022.

[68] Al-Waqidi, Muhammad (1984). Al-Maghazi, Edited by: Marsden Jones, The World of Books, Beirut, 1404 AH

[69] Salem, Elie, (2015).Muslim Administration. Islamic Culture, vol.33 No.1-4. Published by The Islamic Culture Board Hyderabad-Deccan. P 2.

[70] Scanlon, G. T., (1970). Housing and Sanitation: Some Aspects of Medieval Islamic Public Service, in A. Hourani and S. M. Stern (eds.), The Islamic City: A Colloquium (Oxford: Bruno Cassirer, 1970), PP.18,28-29.

[71] Muhammad Ayoub. Shaded And Illuminated Streets, Hotels And Commercial Malls: Urbanization Of The Islamic City Available from: https://www.aljazeera.net/evergreen/longform/2022/1/25/. Accessed: March 2022.

[72] Al-Gilani, A., (2005). Understanding The Image of The Islamic Urban Landscape. A Ph.D. dissertation in design and planning at the University of Colorado at Denver. Colorado, USA, pp.6.

[73] Findlay, Ronald and Kevin O’Rourke. 2007. Power and Plenty: Trade, War and the World Economy in the Second Millennium. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. P.22.

[74]Lombard, Maurice. 1975. The Golden Age of Islam. New York, NY: Elsevier. P.10.

[75] Hanna, Nelly. 1998. Making Big Money in 1600: The Life and Times of Ismail Abu Taqiyya, Egyptian Merchant. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press.

[76]Kennedy, Hugh. 2002. A Historical Atlas of Islam (Second Revised Edition). Leiden: Brill

[77] Abu Shama, Shihab al-Din (1988). Al-Rawdatain in the news of the two countries. Nile Valley Press, Cairo, p. 12.

[78] Ibn Asaker, A., (1998). The history of Damascus City. Dar Al-Fikr, Beirut, vol. 2, page 320.

[79] Al-Hanbali Ibn-Imad (1986). Piece of Gold for golden news, Dar Ibn Katheer, Damascus. vol 4, page 319.

[80] Bianca, Stefano, (1979). A new heart for old cities. Published in: The Unesco courier 44, N. 1, p:15.

[81] Bianca, Stefano. 2000. Urban form in Arab world: Past and present. Zürich and New York, pp:23-72.

[82]Ragette, Friedrich. “Traditional Domestic Architecture of the Arab Region.” (2003).pp:29-91.

[83] Mosques in Islamic History. Available from: https://islamstory.com/ar/artical/3409728/. Accessed April, 2022.

[84] Sarjani, Ragheb (2009). What did Muslims give to the world: Contributions of Muslims to human civilization. Iqra Foundation publishing, distribution and translation, Cairo, pp. 596-603.

[85] van Bavel, AD, Campopiano, M., and Dijkman, J., (2014). Factor Markets in Early Islamic Iraq, c. 600-1100. Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 57 (2014) 262-289.

[86] Metz, A., (2010). Islamic Civilization in the fourth century (AH). Dar Al-Kitab Al-Arabi, Beirut, Lebanon, 4th Edition, Vol. 2, part 21, p: 28.

[87] Al-Maqdisi, Mohammad (1991). The best divisions in knowing the regions. Madbouli Publishing Library, Cairo, p. 182 and 228, 202, 179,365,323

[88] Sahih al-Bukhari, by Muhammad Ismail al-Bukhari, Book of Divorce, Bab al-Laan, Hadith No. 5304.

[89] Sahih al-Bukhari, Book of Literature, Chapter on Mercy of People and Beasts.

[90] Yang Hua, In trade nine-tenths of the livelihood. Available from: http://www.chinatoday.com.cn/Arabic/2006n/0602/p36.htm. Accessed March 2022.

[91] Latief, Hilman. Philanthropy and “Muslim Citizenship” in Post-Suharto Indonesia. Southeast Asian Studies, Vol. 5, No. 2, August 2016, pp. 269-286. Available from: http://englishkyoto-seas.org/2016/08/vol-5-no-2-latief/. Accessed March 2022.

[92] Latief, Hilman. 2010. Health Provision for the Poor: Islamic Aid and the Rise of Charitable Clinics in Indonesia. South East Asia Research 18(3): 503–553.

[93] Fauzia, A. (2017). Islamic philanthropy in Indonesia: Modernization, Islamization, and social justice. Austrian Journal of South-East Asian Studies, 10(2), 223-236.

[94] Jane Pollard, Kavita Datta, Al James, Quman Akli, (2015). Islamic charitable infrastructure and giving in East London: Everyday economic-development geographies in practice. Journal of Economic Geography 16(4). Available from: http://joeg.oxfordjournals.org. Accessed: March 2022.

[95] Akom, A. A. (2007). “Cities as Battlefields: Understanding how the Nation of Islam impacts Civic Engagement, Environmental Racism, and Community Development in a Low Income Neighborhood”. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education. 20 (6): 711–730. Pp:722-723. doi:10.1080/09518390701630858.

[96] Gardell, Matthias (1996). In the Name of Elijah Muhammad: Louis Farrakhan and The Nation of Islam. Durham: Duke University Press.p

[97] Mohamed Abdel Qader Al-Fiqi (2010). The role of the Islamic endowment in development, Islamic Awareness Magazine, Issue 523, March 2010.

[98] Yassin Hisham Yassin Abdel Latif, (2014). The role of the Islamic endowment in urban development. Master’s thesis in Architectural Engineering submitted to the Faculty of Engineering – Cairo University, Cairo Giza – Arab Republic of Egypt 2014

[99] Ibn Battuta: Muhammad bin Abdullah bin Muhammad al-Lawati Abu Abdullah, Ibn Battuta’s Journey called “The Masterpiece of the Priests in the Oddities of the Lands and the Wonders of Travels”, Edited by Ali Al-Muntasir Al-Katani, Beirut, Al-Resala Foundation, 1405 AH, 4th Edition. C 1, p. 118.

[100] Al-Hamawi, Yaqut (1995). Dictionary of Countries, Volume 4 p. 195. Sader Publishing House, Beirut, Lebanon.

[101] Midani, A., (1998). Islamic Civilization: Its Bases, approaches, and pictures of Muslim Application of it, and its impacts everywhere. Al-Qalam Publishing, Damascus, p.168.

[102.] al-Maqdīsī, Muḥammad Ibn-Aḥmad (2003). Riḥlat al-Maqdisī : aḥsan at-taqāsīm fī maʻrifat al-aqālīm ; 985 – 990. Beirut: al-Muʼassasa al-ʻArabīya li-‘d-dirāsāt wa-‘n-našr [u.a.] / The Arab Institute for Studies and Publishing. p. 124

[103] Miran, Jonathan. “Endowing Property and Edifying Power in a Red Sea Port: Waqf, Arab Migrant Entrepreneurs, and Urban Authority in Massawa, 1860s-1880s.” The International Journal of African Historical Studies, vol. 42, no. 2, [Trustees of Boston University, Boston University African Studies Center], 2009, pp. 151–78, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40282383.

[104] Lewis B. (1950) The Fâtimids and the Route to India. Revue de la Faculté de Sciences Économiques de l’Université d’Istanbul, 11, p. 50-54.

[105] Al-Hakim: The Patience Book No. 7307.

[106] Sahih Al-Bukhari, Book of Partnership, Chapter on Partnership in Food, Breasts, and Offers, No. 2354.

[107] Al-Ghazali, A., (2011). Revival of religious sciences. Al-Maarefeh Publishing, Beirut, Lebanon. Vol. 3, p. 250.

[108] Al-Bukhari, The Book of Wills, Chapter of Ottman’s Wills No. (2593).

[109] Al-Sarakhsi, Muhammad (1917). The long path explanation, Dar Al-Maarif Al-Nizamiya Press, Hyderabad, India. vol.1 No. 144.

[110] Ibn al-Qayyim al-Jawziyyah (). Zad al-Ma’ad is guided by the best of people. Edited by Mustafa Atta, Dar al-Kutub al-Ilmiyya, vol. 5, p. 713.

[111] Al-Haythami, Ibn Hajar (2005). Al-Durr Al-Madud in Prayers and Peace be upon the owner of the Maqam Al-Mahmoud, page 66, Dar Al-Minhaj.

[112] Al-Sarjani, Ragheb (2010). Merciful Among them: The Story of Solidarity and Relief in Islamic Civilization. Egypt’s Renaissance for Printing and Publishing.

[113] Muhammad Othman Al-Khasht, (2018). Civil society, pluralism and tolerance in the context of Islamic civilization. Available from: https://www.msf-online.com.

[114] Haddad, M., (2020). Food Production and Food Security Management in Muslim Civilization. Found in: Food Production and Food Security Management in Muslim Civilization – Muslim Heritage.

[115] Albayan, (2020). Al-IbrahimiyahTakiyeht: No one get hungry in Hebron, (2020). Found in: https://www.albayan.ae/one-world/2020-04-25-1.3841262. Accessed August 5, 2021

[116] Al-Ghad newspaper, (2016). Al-Ibrahimiya hospice: 800 years of feeding the poor and destitute. March 13, 2016.

[117] Salleh Shaikh (2019). Islam abhors food wastage. Found in: https://www.nst.com.my/opinion/letters/2019/04/480441/islam-abhors-food-wastage. April 17, 2019. Accessed: July 17, 2021.

[118] Arab Democratic Center, (2017). The effectiveness of civil society institutions in Egypt “2011-2016”. Available from: https://democraticac.de/?p=51285.

[119] Muhammad Siddiq Hassan, M., (2017). The social and economic life of the general class in Iraqi society in the Abbasid era. Humanities Journal of University of Zakho (HJUOZ), Vol. 5, No. 4, pp. 1061–1068, December-2017.

[120] Hussein Amin: Al-Ayaraun and their popular activism in Baghdad, Al-Turath Al-Sha’bi magazine 1963, second issue,

[121] Badri Muhammad Fahd: The General public in Fifth Century Hijri, p. 286

[122] Khathlan S., (1992). The role of Muslim merchants in enhancing and spreading trade between Morocco and West Sudan between the third and fifth centuries (AH).King Abdel Aziz University Journal, Arts and Humanities. pp. 41-74, 1992.

[123] McCall, D, (1971). Islamization of the Western and Central Sudan in the 11th Century. Boston University Papers on Africa, Boston, 1971, Vol. 5, p.3.

[124] Abdel-Hakam, A., (1961). The conquer of Egypt and Morocco, Abdel-Munem Amer Editor, Cairo, Albayan Al-Arabi Committee, 1961 p. 293

[125] Narrated by Ibn Majah No. 2426.

[126] Narrated by Ahmed No. 3/7 (11052), Ibn Majah No 2873, and Al-Tirmidhi No. 2191.

[127] Miqdad, K., (2018). The dialectic of the ruler and the ruled… which one corrupts the other? Found in: https://www.aljazeera.net/blogs/2018/11/16. Accessed June 2022.

[128] Al-Shanqeeti, M., (2015). Scholars and the revolution against tyranny, the mihrab, and the making of leaders (part 7). Available from: https://rimnow.net/w/?q=node/5017. Accessed: March 2022.

[129] Al-Kilani, Alad Al-Razzaq, (1994). From the positions of the great Muslims. The House of Preciousness. page 262.

[130] Gaghaman, A., (2021). The Role of the Private Sector in Economic Resilience During War. Found in: (PDF) The Role of Private Sector in Enhancing Economic Resistance During Aggression (researchgate.net).

[131] The Small and Micro Enterprise Service SMEPS, (2020). Yemen Business Climate Survey Report 2020: Impact of Conflict & Covid-19 on Private Sector Activity. Found in: https://smeps.org.ye/upfiles/posts/SMEPS_File_17-12-2020-8842.pdf.

[132] ibid, Metz, A., (2010). Vol. 2, part 1, pp: 395-396.

[133] Maarouf, N., (1975). Introduction to the Authenticity of Arabic Civilization, Baghdad, 1st Edition, pp.93.

[134] Al-Jahez A., (1932). Insight into trade. Damascus, Syria, p.3.

[135] Udovitch, A. L. (1975). Reflections on the Institutions of Credits and Banking in the Medieval Islamic Near East. Studia Islamica 41: 5-2

[136] Al Ahmad,S., and Abada, I., (2009). Financing Hajj and Umrah in Islamic banking institutions: Jordan Islamic Bank as a model. Yarmouk Research Journal: Series of Human and Social Sciences, Vol.27, A & B. pp 473-488.

[137] Sarjani, Ragheb (2007). The Enabled Encyclopedia of Islamic history. Seventh Edition. Iqra Foundation publishing, distribution, and translation, Cairo, p. 395.

[138] Sigrid Hunke (1964). The sun of Arabia shines on the west. Dar Sader Beirut, Lebanon.

[139] ibid, Lombard, M., (1975). P.10.

[140] Haskins, H., (1927). Studies in the History of Medieval Sciences, Cambridge, UK.

[141] Falco, M., (2008). Ibn Al-Haytham and the Science Theology, Literature, and Art of Medieval and Renaissance Europe. The International Conference on Arabic and Muslims History od Science. Sharjah University.

[142] El-Rooby, A., 1988. EastMeets West, Panorama of Arabic Medicine, in Lectures in History of Arabic Medicine, Riyad, KSA.

[143] ibid, Al-Dali, Ali, (1972). Pp.6-7.

[144] Shawqi, K., and Abaza, N., (2007). Illuminated boards in the Arab Islamic civilization. Dar AlFikr, Damascus, Syria.

[145] Nasser Abdel Rahim (1994). Scientific communication in the Islamic heritage from the beginning of Islam until the end of the Abbasid era, Cairo.

[146] Mohamed Awad, (2011). In the context of Islamic civilization in the Middle Ages. Arab World House. Cairo.

[147] Howard R. Turner (2006). Science when Muslims: an illustrated introduction. Cairo.

[148] Ali, Syed Amir (1938). Brief history of the Arabs and Islamic civilization. Translation of Riyad Raafat, Press, Committee of Authoring, Translation and Publishing, Cairo, p. 475.

[149] Maarouf Najy (1966). The origin of independent schools in Islam. Al-Azhar Press, Baghdad, pp. 5-6, 1966.

[150] ibid, Al-Hamawi, Yaqut (1995). Part 1 p. 414-419.

[151] ibid, Maarouf Najy (1966). p. 14.