The Bodleian Library at the University of Oxford has purchased the medieval Arabic manuscript Kitab Gharaib al-funun wa-mulah al-uyun popularised under the title the Book of Curiosities, an exceptionally rich text on cosmography. The treatise is one of the most important recent finds in the history of Islamic cartography in particular, and for the history of pre-modern cartography in general. The manuscript, a highly illustrated treatise on astronomy and geography compiled by an unknown author between 1020 and 1050, contains an important and hitherto unknown series of colourful maps, giving unique insight into Islamic concepts of the world. Portions of the text are preserved in later copies, but the copy owned by the Bodleian library is the only nearly complete coy and the one to have been extensively studied and released in an electronic edition which represents a model for online publishing of Arabic original manuscripts. This high-quality digital reproduction includes interactive displays, through mouse-over techniques, as well as access to a modern Arabic edition and an annotated English translation.

Table of contents

2. Contents of the Book of Curiosities

2.1. General description of the book’s contents

2.2. Physical description

3. Authorship, date, and provenance

4. Textual history of the treatise

5. Conservation, disbinding, analysis and exhibition

6. The Book of Curiosities online

7. Appendix: Contents of the Book of Curiosities

8. References and further reading

8.1. Publications

8.2. Media coverage

8.3. Links

***

|

|

Figure 1: Title page (folio 1a). © Bodleian Library, MS. Arab. c. 90, fol. 1a. (Source). |

The Bodleian Library at the University of Oxford has purchased a precious manuscript copy of an exceptionally rich text of cosmography in Arabic entitled Kitab ghara’ib al-funun wa-mulah al-‘uyun. This Islamic scientific manuscript contains an important and hitherto unknown series of colourful maps, giving unique insight into Islamic concepts of the world. The manuscript contains a highly illustrated treatise on astronomy and geography compiled by an unknown author in the first half of the 11th century using predominately 10th-century sources. Portions of the treatise are also preserved in later copies, but the copy owned by the Bodleian Library is the only nearly complete version and the one to have been extensively studied and edited in an electronic edition which represents a model for online publishing of Arabic original manuscripts. The treatise is divided into two books: one concerned with astronomy, containing an illustrated discussion of comets and numerous star-groups; the other devoted to geography and to natural and supernatural phenomena, which contains seventeen maps including two world maps of great importance and the earliest recorded maps of the islands of Cyprus and Sicily. Most of the maps are without parallel in any other Arabic, Persian, Greek, or Latin works.

1. Introduction

In June 2002, the Bodleian Library acquired from Sam Fogg, the London dealer in rare books and manuscripts, the unique complete manuscript of a hitherto unknown Arabic cosmographical treatise, the Kitab ghara’ib al-funun wa-mulah al-‘uyun loosely translated as The Book of Strange Arts and Visual Delights. This title was popularised by its editors as the Book of Curiosities. The manuscript has now the shelfmark: Bodleian Library, Dept. of Oriental Collections, MS. Arab. c. 90. It is a copy, probably made in Egypt in the late 12th or early 13th century, of an anonymous work compiled between 1020 and 1050, probably in Egypt. The treatise is extraordinarily important for the history of science, especially for astronomy and cartography, and contains an unparalleled series of diagrams of the heavens and maps of the Earth. The acquisition of the Book of Curiosities was made possible by a series of grants received by the Bodleian Library from UK and Arab funding sources and private individuals. These grants and donations, along with the Arts and Humanities Research Council, have also funded the project to prepare a full study of the treatise, including an edition of the Arabic text and English translation, and to disseminate the results as widely as possible through the internet, exhibitions, and an outreach programme. In particular, the original manuscript was fully edited and displayed online in March 2007 (see the website of the Book of Curiosities). The online edition contains an electronic high-quality reproduction of the original text and its illustrations, linked by mouse-overs to a modern Arabic edition and an English translation (see below section 3 for more details).

|

|

Figure 2: The author’s introduction: extract from the incipit page (MS. Arab. c. 90, folio 1b) and a screenshot of portions of the Arabic text and English translation. |

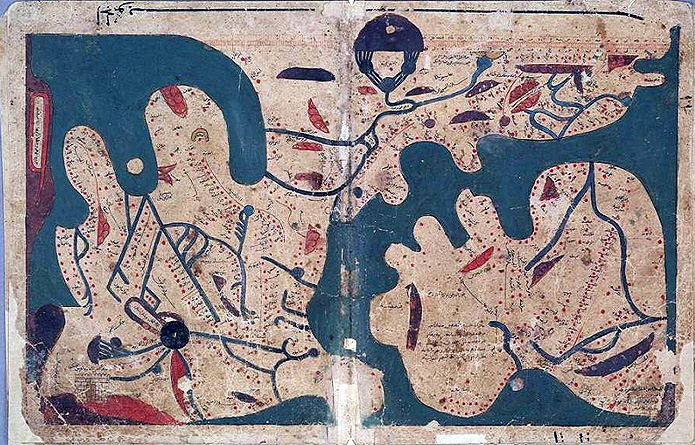

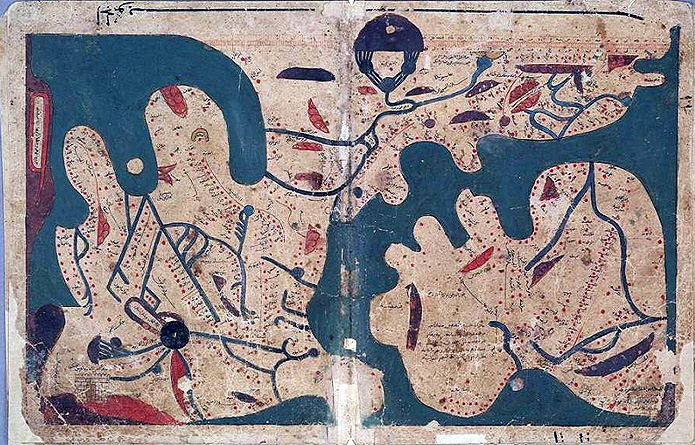

The illustrated anonymous cosmographical manuscript Book of Curiosities contains a unique series of maps and diagrams, most of which are unparalleled in any other medieval work. These include diagrams of star-groups and comets; a rectangular map of the world with a graphic scale (the earliest surviving example of such a map); a circular world map; individual maps of islands and ports in the eastern Mediterranean, including Sicily, Tinnis, Mahdia, Cyprus, and the Byzantine coasts of Asia Minor; maps illustrating the Mediterranean Sea as a whole, the Indian Ocean, and the Caspian Sea; and maps of five major rivers (the Nile, Indus, Oxus, Euphrates, and Tigris).

The manuscript is a copy, probably made in Egypt in the late 12th or early 13th century, of an anonymous work compiled in Egypt between 1020 and 1050. It is extraordinarily important for the history of science, especially for astronomy and cartography, and contains an unparalleled series of diagrams of the heavens and maps of the earth. No less importantly, both the illustrations and the text preserve material gathered from Muslim astronomers, historians, scholars, and travellers, of the 9th to 11th centuries, whose works are now either lost or preserved only in fragments.

This manuscript (and even the treatise it contained) was totally unknown to scholars prior to its being offered for sale at auction in London on 10 October 2000 at Christie’s. At auction the manuscript was purchased by Sam Fogg, a well-known London dealer in rare books and manuscripts. Not long thereafter he offered it to the Bodleian Library at a price well under the true market value. In June of 2002, following an extensive fund-raising effort, the Bodleian Library celebrated the acquisition of this unique Arabic manuscript [1].

|

|

Figure 3: Sample of thumbnail views showing pages 1 of 9 (images 1-12 of 98 total). © The Bodleian Library. (Source). |

2.Contents of the Book of Curiosities

The book contains five chapters (maqala-s), of which only the first two were copied in the Bodleian manuscript. The first chapter, on celestial matters, is composed of 10 sections. The second, on the earth, is divided into 25 sections. The original book consisted of three additional chapters devoted to horses, camels and hunting. These chapters were assumed to be not preserved in any manuscript around the world, although five partial copies of the first chapter, all of later date, are known to be preserved in Cairo, Milan, Bodleian, Mosul and Algiers.

Another copy of the book, however, is in the Syrian national library in Damascus; it was not mentioned in connection with the electronic edition of the Bodleian Library manuscript and has not yet been fully studied. Originally it was kept in the Waqfiyyah (Endowment) Library in Aleppo before moving the manuscripts of Aleppo to the Syrian national library in Damascus (al-Asad Library). It is composed of 201 folios (402 pages). Its chapters’ contents are given at the start of the treatise as follows: chapter 1: 10 sections; chapter 2: 25 sections; chapter 3: 4 sections; chapter 4: 19 sections; chapter 5: 21 sections. It appears, however, that it is an incomplete copy also lacking the final chapters. It contains maps and astronomical diagrams in at least 14 places, but it does not contain as many maps and illustrations as does the Bodleian manuscript, which has a total of 68 maps, diagrams, and illustrastions and is, hence, the best known documentary source for the Book of Curiosities. The scribe completed copying the Damascus manuscript in Rabi I, 972H (October 1564).

2.1. General description of the book’s contents

The Bodleian Library manuscript of the Book of Curiosities contains a remarkable series of early maps and astronomical diagrams, most of which are unparalleled in any Greek, Latin or Arabic material known to be preserved today. The volume contains a single Arabic treatise in two books. The first book, on celestial matters, is composed of 10 chapters, and begins with a description of the heavens and their influence upon events on earth. It contains a number of unique illustrations and rare texts, including an illustrated discourse on comets and several pages depicting various prominent stars nearby the ‘lunar mansions’—star-groups near the ecliptic whose risings and settings were traditionally used to predict rain and other meteorological events. The author’s interest here is primarily astrological and divinatory, and no mathematical astronomy is presented.

|

|

Figure 4: Diagram of the universe: Book 1, Chapter 1 “On the extent of the celestial sphere, and a summary of the sayings of the scholars regarding its knowledge and structure” (MS. Arab. c. 90, fols. 2b-3a). © The Bodleian Library. (Source). |

The second book, on the earth, is divided into 25 chapters. According to the author, this second book is largely dependent upon the Geography of Ptolemy. In general, though, the author’s interest is descriptive and historical rather than mathematical. Along with geographical and historical texts, the author provides two world maps, one rectangular and one circular. He then follows with maps of the great seas known to him, which were the Indian Ocean, the Mediterranean and the Caspian. The author was particularly interested in depicting the shores of the Mediterranean, of which he probably had first-hand knowledge. Besides the detailed schematic map of the coasts and islands of the Mediterranean, the treatise also contains unique maps of Sicily, Cyprus and the commercial centres of al-Mahdiyah in North Africa and Tinnis in Egypt. The treatise also includes five unique river-maps of the Nile, the Euphrates, the Tigris, the Oxus, and the Indus. The concluding five chapters describe ‘curiosities’ such as monstrous animals and wondrous plants.

According to a later manuscript containing a partial copy of the first book, the original treatise consisted of three additional books, devoted to horses, camels and hunting. These chapters were not copied in the manuscript copy held at the Bodleian library, but we know of their existence through parallel manuscripts containing excerpts from the original treatise (see below section 4).

2.2. Physical description

The volume consists of 48 folios (96 pages), each measuring 324 x 245 mm. Pages without illustrations have 27 lines of text per page. The treatise begins with a dedication to an unnamed patron and an abbreviated table of contents. The manuscript copy is incomplete, however, for the copyist has omitted the eighth and ninth chapters of the second book, and the manuscript has lost part of the penultimate chapter and all of the last one.

|

|

Figure 5: The oldest extant rectangular world map: Book 2, Chapter 2 (MS. Arab. c. 90, fols. 23b-24a). © The Bodleian Library. (Source). |

The paper of the manuscript is a lightly glossed, biscuit-brown paper; it is sturdy, rather soft, and relatively opaque. The paper has thick horizontal laid lines, slightly curved, and there are rib shadows, but no chain lines or watermarks are visible. The thickness of the paper varies between 0.17 and 0.20 mm and measures 3 on the Sharp Scale of Opaqueness; the laid lines are 6-7 wires/cm, with the space between lines less than the width of one line. The paper would appear to have been made using a grass mould. Paper of such construction was produced in Egypt and Greater Syria in the 13th and 14th centuries [2].

The text is written in a medium-large Naskh script in dense black ink. Headings are in warm-red ink. The illustrations are labelled in a similar but much smaller hand. Both hands are closer in many of their characteristics to those of copyists known to have worked in Greater Syria at the end of the 12th century or early 13th century than to the hands of securely dated and located products of the 14th century. The text area has been frame-ruled. The copyist displays a disconcerting carelessness, if not ignorance, in his transcription of many words, especially non-Arabic place-names, and diacritical dots are frequently omitted, making the interpretation of certain words difficult. Some illustrations, such as those depicting comets or small islands, have traces of gold or silver sprinklings. Some areas in the maps may have been over-painted or coated in a shiny lacquer-like material that is now crackled and crazed.

The paper has some damp-staining, foxing, and wormholes, and there is considerable soiling and grime near the edges of the pages, which have been trimmed from their original size with the loss of some text and marginalia. Numerous repairs have been made to the paper at various times. At the end of the volume, in the gutter, are narrow remnants of two folios that have been cut from the volume, corresponding to a missing chapter on curious animals.

|

|

Figure 6: Map of al-Mahdiyah: Book 2, Chapter 13 “On the peninsula of al-Mahdiyah” in Ifriqiya (modern Tunisia) (MS. Arab. c. 90, fol. 34a). © The Bodleian Library. (Source). |

3. Authorship, date, and provenance

The author of the Book of Curiosities is not named and has not been identified, although he refers to another composition of his titled al-Muhit (‘The Comprehensive’). On the basis of internal evidence, we can suggest that the treatise was composed in the first half of the 11th century, probably in Egypt. The copy we have today is more recent and appears to have been made some hundred and fifty to two hundred years later. Although the copy is undated and unsigned, the paper, inks, and pigments appear consistent with Egyptian-Syrian products made from the early 13th through the 14th century.

Our author recognized the legitimate authority of the Fat?imid imams who came to power in Ifriqiyah (modern Tunisia) in 909 and ruled at Cairo from 973 until their dynasty was brought to an end by Salah al-Din (Saladin) in 1171. At their heyday, the Fatimids ruled all over Syria, Egypt and North Africa. Whereas the ‘Abbasid caliphs of Baghdad were recognized as the rightful leaders of the Muslim community by the Sunni majority, the Fatimid imams—who claimed to be the biological descendants of the Prophet Muhammad through his daughter Fatimah—were recognized as legitimate by a faithful minority of Isma’ili Muslims. Our author not only opens his work with an explicit acknowledgement of the Fatimids but also, further on, gives a brief but highly doctrinaire history of the rise of the dynasty, from the accession of the first imam, al-Mahdi, to the defeat of Abu Yazid (al-dajjal, the Antichrist) by his son, al-Qa’im.

The geographical focus of the Book of Curiosities is Muslim commercial centres of the 9th-to 11th-century eastern Mediterranean, such as Sicily, the textile-producing town of Tinnis in the Nile Delta, and Mahdiyah in modern Tunisia. The author is equally acquainted with Byzantine-controlled areas of the Mediterranean, such as Cyprus, the Aegean Sea, and the southern coasts of Anatolia. The author’s occasional use of Coptic terms and Coptic months, together with the allegiance to the Fatimid caliphs based in Cairo, suggest Egypt as a likely place of production.

|

|

Figure 7: Map of the Indian Ocean: Book 2, Chapter 7: “On the cities and forts along the shore [of the Indian Ocean]” (MS. Arab. c. 90, fols. 29b-30a). © Bodleian Library. (Source). |

The treatise was almost certainly composed before 1050. The tribal group of the Banu Qurrah are mentioned in chapter 6 of Book 2 as inhabiting the lowlands near Alexandria. As the Banu Qurrah are known to have been banished from the region of Alexandria by the Fatimid authorities in 1051–1052, it is very likely that this treatise was written before that date. Since Sicily is described as being under Muslim rule, the treatise could definitely not have been composed later than the Norman invasion of Sicily in 1070.

The last dated event mentioned in the treatise is the construction buildings for merchants in the city of Tinnis in 1014-1015. Moreover, al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah, the Fatmid ruler of Egypt and Syria from 996 to 1021, is referred to in the chapter on Tinnis as if he were no longer reigning. Therefore, the treatise was probably composed after 1021.

4. Textual history of the treatise

While the chapters containing the maps are not known to be preserved in later copies or incorporated into other treatises, portions of Book 1 (on celestial matters) of the Book of Curiosities, as well as the first chapter of Book 2 (on the measurement of the earth) are found in five unillustrated manuscripts (all much later copies) of treatises having the same title (Ghara’ib al-funun wa-mulah al-‘uyun) but slightly differing contents. These sections of Book I, and the first chapter of Book 2, are preserved in Cairo, Dar al-Kutub, miqat MS 876, fols. 1a-18b copied in 1641 [1051 H]; in Milan, Biblioteca Ambrosiana, MS & 76 sup., folios 2a-67b; and also partially in a manuscript written in Karshuni (Arabic in Syriac script) and now in the Bodleian Library (MS Bodl. Or. 68, fols. 37a-143b). Of these three manuscripts, the one in Milan is closest in content to the first book of the Bodleian Library manuscript, but all three manuscripts proved useful in editing various portions of Book I. Two other copies are recorded as being in Mosul and in Algiers, but they were unavailable for comparison.

|

|

Figure 8: Map of the Mediterranean Sea: Book 2, Chapter 10: “On the Western Sea, that is the Syrian Sea, its harbours, islands and anchorages” (MS. Arab. c. 90, fols. 30b-31a). © Bodleian Library. (Source). |

In addition, the introduction and the last chapters of the second book, which depict ‘curiosities’ such as monstrous animals and wondrous plants, were included in a treatise on animals compiled in 1741 [1154 H] by Muhammad ibn ‘Abd al-‘Aziz al-Shafi’i al-Halabi al-mutatabbib, and now preserved in Gotha (Forschungs- und Landesbibliothek, MS orient. A 2066, folios 147b-156b). The author specifies that he extracted and used portions of the Book of Curiosities of the Sciences and Marvels of the Eyes, which he calls ‘a splendid book’ (kitab jalil) though he does not provide the name of its author. The compiler of the Gotha manuscript goes on to say that he selected the chapters on semi-human creatures at the edges of the inhabited earth as well as those on wondrous birds and fishes from the Book of Curiosities and then followed those with material taken from his own composition titled The Comprehensive Summary (jami‘ al-jawami‘) on the Occult Properties and Uses of Animals. This Gotha manuscript contains the full text of the original introduction to the treatise, describing three additional books on horses, camels and hunting in addition to the two books on the heavens and the earth copied in the present manuscript. The manuscript now in Gotha has also been very useful in editing chapters 20 through 24 of Book 2 of the Book of Curiosities, which the compiler reproduced in full; the manuscript also contains the final chapter, 25, that is missing from our copy of the Book of Curiosities. The compiler of the Gotha manuscript was not interested in the celestial material of the Book 1, nor was he interested in the geographical and cartographical portions of Book 2.

A catalogue of books prepared in the 17th century by the Turkish lexicographer Hajji Khalifa (Katip Çelebi, d. 1657) mentions a treatise of very similar title, Curiosities of the Sciences, Marvels for the Eyes, and Pleasures of the Passions for the Seeker of Journeys?(Ghara’ib al-funun wa-mulah al-‘uyun wa-nuzhat al-‘shshaq li’-talib al-mushtaq), with an identical opening line. In his catalogue, Haji Khalifa mentions that the treatise is concerned with the stars and the climes but fails to mention an author. A later variant manuscript of the same catalogue attributes the treatise to ‘Abd al-Ghani ibn Husam al-Din Ahmad ibn al-‘Uryani (or al-‘Arabani) al-Misri, who is said to have died in 1450. This author is not otherwise known, but is likely to be a member of the 15th-century Ibn al-‘Uryani scholarly family from Cairo. On the basis of this variant manuscript of Hajji Khalifah, Alexander Nicoll, who prepared in 1835 one of the early catalogues of Arabic manuscripts in the Bodleian Library, attributed the Karshuni copy of Ghara’ib al-funun wa-mulah al-‘uyun in the Bodleian to Ibn al-‘Uryani (whom he called al-‘Arabani). Later cataloguers followed him, attributing all other manuscripts bearing the title of Ghara’ib al-funun to this 15th-century author. This attribution should be treated with caution, as the present manuscript under study demonstrates beyond doubt that a treatise of that name and description was composed in the first half of the 11th century. The similarity of the title and the opening lines suggest that Ibn al-‘Uryani’s treatise was closely related to the earlier treatise, but we do not know at present whether his work was a copy or an abridgement of the 11th-century work, and whether it, rather than the original work, was the source for the later manuscripts described above.

5. Conservation, disbinding, analysis and exhibition

When acquired by the Bodleian Library, the volume was contained in an Ottoman binding of, possibly, 18th or 19th century date; the binding was too small for the manuscript and in extremely poor condition. The first folio of the manuscript has staining which indicates that an earlier binding included an envelope flap. At present, the volume is disbound with the binding removed and stored separately. The conservation laboratories of the Bodleian Library will ultimately rebound manuscript and give it a new binding meeting modern standards of preservation and conservation.

|

|

Figure 9: Map of Sicily: Book 2, Chapter 12: “Brief description of the largest islands in these seas” (MS. Arab. c. 90, fols. 32b-33a). © Bodleian Library. (Source). |

A preliminary analysis of the pigments was conducted in the conservation workshop of the Bodleian Library by Dr Sandra Grantham, a consultant paper conservator, using optical microscopy. A full analysis using Raman Spectroscopy was subsequently carried out by Dr Tracey Chaplin at the Christopher Ingold Laboratories, University College London. Six pigments were identified in the illustrations: cinnabar (red), orpiment (yellow), lazurite (blue), indigo, carbon-based black and basic lead carbonate (a ‘lead white’); four further pigments (a golden material, a green pigment, the purple pigment used to depict city walls, and the blue component of the dark green pigment mixture on certain folios) could not be identified. No evidence of modern inks or pigments was revealed. The results of the scientific analyses are completely consistent with the suggested origin and age of the manuscript [3].

With the manuscript disbound for conservation purposes, the exhibition of its numerous illustrations became possible. The circular world map in the manuscript was chosen by the National Art Collections Fund (one of the major contributors toward the acquisition of the manuscript) for display on the occasion of the exhibition Saved! 100 years of the National Art Collections Fund, held at the Hayward Gallery, London (23 October 2003-18 January 2004) [4].

An exhibition of most of the maps and illustrations was held in the Bodleian Library’s Exhibition room from 14 June to 30 October, 2004. Titled Medieval Views of the Cosmos: Mapping Earth and Sky at the time of the Book of Curiosities, the exhibition included comparative materials from the Islamic and the Christian worlds illustrating roughly contemporary developments in mapping.

To complement the exhibition, the Bodleian published an illustrated small book entitled Medieval Views of the Cosmos: Picturing the Universe in the Christian and Islamic Middle Ages, by Evelyn Edson and Emilie Savage-Smith [5]. Produced in lieu of a catalogue, the subject of this book is broader than that of the exhibition, but it still provided an opportunity to reproduce in high-quality photographs several of the maps from this manuscript along with diagrammatic explanations.

|

|

Figure 10: Screenshot of the mouse-over technique (Sources of the Nile: Book 2, Chapter 17, MS. Arab. c. 90, fol. 40a). © Bodleian Library. (Source). |

6. The Book of Curiosities online

As said above, the Bodleian library manuscript copy of the Book of Curiosities was made available on internet in a dedicated website Medieval Islamic Views of the Cosmos: The Book of Curiosities devoted for full description and edition of the manuscript, together with photos of all its pages. This electronic publication was produced by the Bodleian Library in collaboration with The Oriental Institute, University of Oxford. The edition and translation were prepared by Dr E. Savage-Smith and Dr Y. Rapoport. The publication of the treatise is mounted on a dedicated website employing a new method for publishing medieval maps. Indeed, the website employs a new method for publishing maps with a mouse-over facility that allows the user to enlarge the labels and read the Arabic text with the translation alongside the label.

The website contains an electronic high-quality reproduction of all the folios of the original manuscript, linked by mouse-overs to an Arabic edition and an annotated English translation of the text of the treatise as well as the labels on the maps. The site also allows users to search for English and Arabic terms, consult an extensive glossary, and study explanatory diagrams. The treatise has been available in its entirety since March of 2007.

The online edition of the Book of Curiosities is the first electronic publication of a work of medieval Islamic cartography, promoting research in a relatively neglected field. It is also intended to be widely used as a teaching tool in graduate and undergraduate courses on Islamic history, Islamic culture, and the history of science. For younger students, the website contains a downloadable Teacher’s Pack based on portions of the manuscript, suitable for Key Stage 3 of the UK National Curriculum (aimed at 11-14 year olds).

|

|

Figure 11a and 11b: View of the Arabic text and English translation of MS. Arab. c. 90, fol. 40a. © Bodleian Library. (Source 1 – Source 2). |

The achievement of the electronic edition of the manuscript was made possible by donations that were intended to provide funds for the conservation, pigment analysis, and digitisation of the manuscript, the exhibition of the manuscript for the general public, the preparation of materials for schools based on portions of the manuscript, and the creation of website for the electronic edition. Moreover, the donators supported the project (partially funded as well by the Arts & Humanities Research Council) to prepare a full study of the treatise, including an edition of the Arabic text with English translation, all mounted on the above-mentioned website. The recently established Khalili Research Centre for the Art & Material Culture of the Middle East provided a home for the execution of the project.

The website contains an electronic high-quality reproduction of the original text and its illustrations, linked by mouse-overs to a modern Arabic edition and an English translation. This electronic form of publication is particularly suited to the Book of Curiosities, both because the manuscript is in a fragile state and because much of the material in the treatise is in the form of diagrams and maps. The editors hope that the electronic publication will allow the edition of this unique manuscript to be an on-going collective enterprise, where comments and feedback from users will continually enrich the understanding of the manuscript.

The website allows the visitor to view all the images and pages in the Book of Curiosities in original size and colour, to follow mouse-over links to read an English translation and an Arabic edition of any unit of text or map label, to search for English and Arabic terms, and locate them in the manuscript, to consult explanatory diagrams and to download a Teacher’s Pack [6].

The teachers’ Pack explores the themes of the Book of Curiosities which are to do with the Earth and the Heavens from the perspective of an 11th-century writer. It can be used at Key Stage 3 of the UK National Curriculum (aimed at 11-14 year olds) in the study of history, geography, English and science (Download Teachers’ Pack). The Teachers’ Pack offers guidance notes for teachers and task sheets for students, together with copies of the maps and diagrams containing the primary source materials needed for students to carry out assigned tasks. The Book of Curiosities is a valuable learning resource. It can contribute to the study of the early history of cartography and geography, the study and evaluation of historical sources and the Islamic contribution to world knowledge.

The electronic edition is enriched by a huge sum of 397 Bibliographic References, sorted in alphabetical order (see References). And finally a search engine (see Search) in Arabic text or English translation, in the Glossary, the References and the Footnotes.

7. Appendix: Contents of the Book of Curiosities

The contents of the book are described from the Bodleian manuscript as reproduced in the electronic edition. The latter is structured as follows:

Table of contents

8. References and further reading

8.1. Publications

8.2. Media coverage

8.3. Links

End Notes

[1] Most of the factual data we rely upon in this description of the manuscript, its acquisition and its edition and study are extracted from the website of the Book of Curioisties, especially from the sections “Project Description” and “History” [of the edition and translation project].

[2] For similar Islamic papers, see Helen Loveday, Islamic Paper: A Study of the Ancient Craft (London, 2001).

[3] The results of the Raman spectroscopic analysis have been published in Tracey D. Chaplin, Robin J. H. Clark, Alison McKay and Sabina Pugh, “Raman spectroscopic analysis of The Book of Curiosities of the Sciences and Marvels for the Eyes“, in the Journal of Raman Spectroscopy (John Wiley & Son, UK), vol. 37, 2006.

[4] See the exhibition catalogue: Saved! 100 years of the National Art Collections Fund, edited by Richard Verdi. London: Hayward Gallery, 2003, p. 278, item 225.

[5] Medieval Views of the Cosmos: Picturing the Universe in the Christian and Islamic Middle Ages by Evelyn Edson, Emilie Savage-Smith. Oxford: The Bodleian Library, 2004, Paperback, 128 pages, 65 colour illustrations and 15 diagrams. An expanded German version was published: E. Edson, E. Savage-Smith, and A-D. von den Brincken, Der mittelalterliche Kosmos: Karten der christlichen und islamischen Welt, Darmstadt: Primus Verlag, 2005.

[6] Among the other facilities provided in connection with the electronic edition of the Book of Curiosities, there is a ‘user guide’ that can be downloaded in PDF format: User Guide.

4.9 / 5. Votes 183

No votes so far! Be the first to rate this post.

Muslim Heritage:

Send us your e-mail address to be informed about our work.

This Website MuslimHeritage.com is owned by FSTC Ltd and managed by the Foundation for Science, Technology and Civilisation, UK (FSTCUK), a British charity number 1158509.

© Copyright FSTC Ltd 2002-2020. All Rights Reserved.