Two science histories dissect the transfer of knowledge between the Greco–Islamic and European civilizations, and put right the impression that the flow was one way, explains Yasmin Khan in a recently published article (Nature, vol 458, 12 March 2009).

Figure 1. Front covers of two recently published books on the scientific legacy of the Islamic tradition and its impact on modern science: Aladdin’s Lamp: How Greek Science Came to Europe Through the Islamic World by John Freely (Knopf, 2009) and Science and Islam: A History by Ehsan Masood (Icon Books, 2009).

***

Note of the editor

First published 3rd April 2009 in Muslim Heritage old website. This article is based on Yasmin Khan “Shining light upon light” published in Nature, vol. 458, 12 March 2009, pp. 149-150; doi:10.1038/458149a. See the article online at the website of Nature: Full Text and PDF version. The article is a review of Aladdin’s Lamp: How Greek Science Came to Europe Through the Islamic World by John Freely (Alfred Knopf, 2009) and Science and Islam: A History by Ehsan Masood (Icon Books, 2009). We publish an extract from the original article (as allowed by Nature graciously), with slight editorial changes, and add further materials and resources. We thank Yasmin Khan and the editorial board of Nature for allowing partial republishing.

***

Figure 2. Ottoman astronomers at work around Taqī al-Dīn at the Istanbul Observatory. Source: Istanbul University Library, F 1404, fol. 57a.(Source)

It has been widely accepted that the Islamic civilization had merely a bridging role in preserving the wealth of inherited ancient Greek knowledge ready for future consumption by the West. This pervasive belief, now known to be a damaging distortion of history, is explored in two new books. In Aladdin’s Lamp, John Freely writes a captivating account of the transfer of scientific ideas between these civilizations.

Interlacing historical events with finesse, his story has a nostalgic quality that makes for escapism but falls short of convincing. At first glance, we assume that Freely will offer us an exposé of the central part the Islamic world played in the pursuit of science, and the key contributions it made. Instead, it quickly transpires that Freely’s handling of Islamic discoveries could be construed as damning with faint praise in comparison with his treatment of Greek knowledge.

Freely introduces his book by declaring that “Modern Science traces its origins back to ancient Greece”, arousing suspicion that his motive is to venerate the ancient Greeks as the progenitors of scientific ideas, and to suggest that later civilizations should be viewed as being in their shadow. By the end of the book it becomes apparent that this suspicion is founded. Yet Freely’s thesis raises the question of whether the emergence of modern science, as practised today, really was spearheaded by the ancient Greeks.

Figure 3-4. (Left) Nasir al-Din al-Tusi pictured at his writing desk at Maragha observatory that he founded in 1259. © The British Library (Source). (Right) Ottoman astronomers studying the moon and the stars in a miniature dating from the 17th century held in a manuscript owned by Istanbul University Library. (Source).

Old-school historians were adamant that the scientific revolution emerged in the 16th and 17th centuries, when the original sources of classical Greek thinking were ‘rediscovered’ by Europe. Others, such as Ehsan Masood, beg to differ.

In Science and Islam — the accompanying book to a BBC television and radio series that focuses on science in the Muslim world — he shows that the information flowed in two directions. Through a translation movement that began in the early 9th century, the Islamic world built extensively on Greek ideas, as well as on knowledge from other civilizations, to develop new theories. A golden age for the Islamic civilization, this prolific period spanned more than 800 years. Scientific, technological and engineering endeavour was cultivated to such an extent that it attracted interest in Europe, which was supposedly languishing in the Dark Ages.

Figure 6. 3D Construction of the Third Water Raising Device.

Both books are opportune and contribute to the long-overdue popularization of the multicultural history of science. No doubt a flurry of similar books will shortly appear, especially given the current political climate coupled with the underpinning role that science has in modern society and the possibilities for development it offers in reviving the Middle East. Yet what is still needed is an updated popular historiography that can span the full breadth of world history and position the outputs of Islamic science into a wider context. That is worth waiting for.

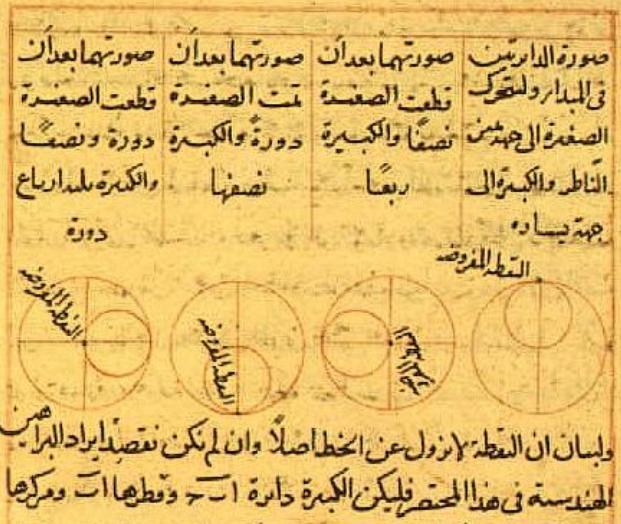

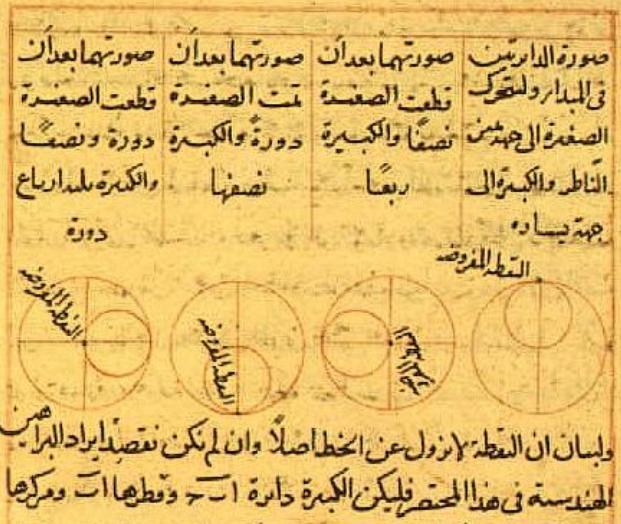

Figure 6. Diagram of the famous Tusi couple as depicted in the 13th-century Arabic MS 319 (folio 28v) held at the Vatican Library; click here for an animation. The Tusi couple, as it was called by Edward Kennedy in 1966, is a device created by Nasir al-Din al-Tusi (1201-1274) based on a theorem that converts uniform circular motion into linear motion. It was a key ingredient in several models that eliminated the eccentric and/or the equant introduced by Ptolemy. It is one of several late Islamic astronomical devices bearing a striking similarity to models in Copernicus’ De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (1543). Historians suspect that Copernicus had access to an Islamic astronomical text. See George Saliba, “Whose Science is Arabic Science in Renaissance Europe?” for a thorough discussion of Al-Tusi’s model and the interactions of Arabic and Latin astronomers, and Eric W. Weisstein on Tusi Couple.

***

Aladdin’s Lamp: How Greek Science Came to Europe Through the Islamic World by John Freely. Random House, Inc./Knopf Publishing Group, 2009. Hardcover, 320 pp. ISBN: 9780307271327.

About the Author

John Freely was born in Brooklyn, New York, and grew up there and in Ireland before joining the U.S. Navy at seventeen for the last two years of World War II. Since 1960 he has taught physics and the history of science at Bosphorus University in Istanbul, with intervals in New York, Boston, London, Athens, and Venice. He is the author of more than forty books. He lives with his wife in Istanbul.

Table of contents

List of Illustrations – ix

Introduction – 3

1. Ionia: The First Physicists – 5

2. Classical Athens: The School of Hellas – 23

3. Hellenistic Alexandria: The Museum and the Library – 38

4. From Athens to Rome, Constantinople, and Jundishapur – 61

5. Baghdad’s House of Wisdom: Greek into Arabic – 72

6. The Islamic Renaissance – 83

7. Cairo and Damascus – 95

8. Al-Andalus, Moorish Spain – 106

9. From Toledo to Palermo: Arabic into Latin – 120

10. Paris and Oxford I: Reinterpreting Aristotle – 137

11. Paris and Oxford II: The Emergence of European Science – 149

12. From Byzantium to Italy: Greek into Latin – 164

13. The Revolution of the Heavenly Spheres – 178

14. The Debate over the Two World Systems – 191

15. The Scientific Revolution – 211

16. Samarkand to Istanbul: The Long Twilight of Islamic Science – 226

17. Science Lost and Found – 237

18. Harran: The Road to Baghdad – 249

Acknowledgments – 257

Illustration Credits – 259

Notes – 261

Bibliography – 275

Index

***

Science and Islam: A History by Ehsan Masood. Icon Books: 2009. Hardcover: 256 pp. ages. ISBN-10: 1848310404. Read a sample chapter and see the book’s blog site here.

About the author

Ehsan Masood is Acting Chief Commissioning Editor at Nature and teaches international science policy at Imperial College London. He also writes for Prospect and OpenDemocracy.net and is a regular panellist on BBC Radio 4’s Home Planet.

Table of contents

List of illustrations – vii

A note on language – x

Prologue – iii

1 The Dark Age Myth – 1

Part I: The Islamic Quest 15

2. The Coming of the Prophet – 17

3. Building Islam – 29

4. Baghdad’s Splendour – 39

5. The Caliph of Science – 55

6. The Flowering of Andalusia – 65

7. Beyond the Abbasids – 81

Part II: Branches of Learning 93

8. The Best Gift From God – 95

9. Astronomy: The Structured Heaven – 117

10. Number: The Living Universe of Islam – 139

11. At Home in the Elements – 153

12. Ingenious Devices – 161

Part III: Second Thoughts 167

13. An Endless Frontier – 169

14. One Chapter Closes, Another Begins – 187

15. Science and Islam: Lessons From History – 207

Timeline – 217

Acknowledgements – 223

Bibliography – 227

Index – 233

Other articles by Yasmin Khan

Resources and further reading

1. BBC – Yasmin Khan Interview on “1001 Inventions” (RealPlayer) 09/03/2006.

2. Broadcast about the 1001 Inventions exhibition presented by Vincent Doud, BBC World Service (08/03/2006).

Ground breaking achievements in Islamic technology: Al-Jazari and Taqi al-Din

1. A Special section on Al-Jazari: 800 Years Later: In Memory of Al-Jazari, A Genius Mechanical Engineer – https://muslimheritage.com/?s=al-Jazari

2. A Special Section on Taqi al-Din Ibn Ma’ruf:

Yasmin Khan is Curator Team Manager at the Science Museum, London SW7 2DD, UK, part of the National Museum of Science and Industry. She is also a key associate of the Foundation for Science, Technology and Civilisation (FSTC) and member of its consulting body Muslim Heritage Awareness Group. Yasmin Khan was previously the project manager for the 1001 Inventions exhibition until its inaugural launch in 2006.

4.9 / 5. Votes 187

No votes so far! Be the first to rate this post.

Muslim Heritage:

Send us your e-mail address to be informed about our work.

This Website MuslimHeritage.com is owned by FSTC Ltd and managed by the Foundation for Science, Technology and Civilisation, UK (FSTCUK), a British charity number 1158509.

© Copyright FSTC Ltd 2002-2020. All Rights Reserved.