Cities may flourish during a certain period of history and then they may lose their importance, depending on various factors. However, cities that are built around a religious tradition tend to prosper and grow in importance. This is particularly true in our modern times, when travel has become fast and easy in the pre-Covid 19...

Figure 1. Article Banner

Cities may flourish during a certain period of history and then they may lose their importance, depending on various factors. However, cities that are built around a religious tradition tend to prosper and grow in importance. This is particularly true in our modern times, when travel has become fast and easy in the pre-Covid 19 world.

Perhaps Makkah, or Mecca, is the best known religious city in the world today, because of its function as the centre of an essential Islamic duty, the hajj, or pilgrimage, which is incumbent on every Muslim, man or woman, once in their lifetime. The Kaabah, which is the cubic building enshrouded with a Black drape at the centre of the Sacred Mosque in Makkah, is the place to which all Muslims face when they offer their daily prayer, wherever they are. For an informed reading on the Kaabah and its orientations, see the recent publication by Simon O’Meara[1]. This association between Islam and Makkah is taken for granted by all people.

When examining the history of a particular city, a historian will look at the records of its own people and what they tell us about their city in different periods. It is of interest to look at the mention of Makkah by its people prior to the time of Prophet Muhammad and the start of Islam (in 610 CE, in Makkah, according to Arab and Islamic tradition).

What is very helpful in this study is the fact that Arabic has not changed much over the centuries. This is due to the Qur’an, which has preserved its construction, derivative character, grammar and vocabulary. We are able to read today what was written in Arabic long before the start of Islam in the seventh century. At that time, the Arabs took much pride in their language, particularly in poetry, which is still considered highly relevant in academic circles. Poems from pre-Islamic days are still studied in secondary schools and universities throughout the Arab world. There are some difficulties encountered by students, but this is natural because of the social development that has introduced new terms and discarded obsolete ones, but an educated Arab would have no difficulty with grammar and construction of Arabic poetry written fifteen or sixteen centuries ago, or even earlier.

The Arabs of pre-Islamic days were exceedingly fond of their poetry and each tribe celebrated the growth of a fine poet, considering him or her a great asset. Some poets became so famous because of the extra care they used with their poetry. It is said that when they composed a particularly important poem, they resorted to immortalize it by writing it on a scroll and displaying it on the wall of the Kaabah, for pilgrims to read. Thus, we have the ‘displayed’ or ‘hanged’ poems (Al-Mu’allaqat)[2], which are known, at least in part, to many school children and university students. We note here that there is a dispute amongst historians on whether these poems were actually physically hung on the Kaaba walls, or named as such, to mean being hung in the minds and hearts of people. However, none of the historical sources denies the pre-Islamic existence of these poems.

Figure 2. Art work on Al-Mu’allaqat 3, 1978. Indian ink on paper, 92 x 64 cm. © Dia Al-Azzawi. Courtesy Galerie Claude Lemand, Paris. (Source) (Archived)

A particularly relevant point to the questions raised by those who question the existence of Makkah prior to Islam is whether any mention of Makkah occurs in any of these important poems.

One of these important poems was by Zuhair ibn Abi Sulma[3]. He died in 609, i.e. one year before the start of the Islamic message. He was one of three poets of that era whom critics consider the best of Arab poets. What distinguishes his poetry is that it is serious, finely constructed and full of wisdom. His two sons Bujair and Kaab were also poets, but Bujayr embraced Islam early and was a companion of the Prophet, while Kaab did not. He abused Islam and the Prophet in his poetry, until shortly before the Prophet’s death when he also embraced Islam. In his most famous poem, displayed at the Kaabah, Zuhair follows the standard pattern followed at the time, which begins the poem with a few lines addressed to a former love that has long departed with her tribe. This normally takes the form of visiting the ruins of her tribe’s former quarters. His fourth line in the poem says:

I stopped there after twenty pilgrimage seasons, and I could hardly recognize the place.[4]

وقفت بها من بعد عشرين حجة فلأياً عرفتُ الدارَ بعد توهّم

He is dating his last visit to his love as ‘twenty pilgrimage seasons’ earlier. It is well-known that a pilgrimage is an annual event. We need to remember that the pilgrimage, or the hajj, was not started by Islam, but by Prophet Abraham who is believed to have built the Kaabah many centuries earlier. This is a clear statement confirming that the pilgrimage to Makkah was an established tradition and that the Arabs, who did not have a regular calendar, estimated time and number of years by this tradition.

The sixteenth line of the poem says:

I swear by the House around which walked the men who built it, belonging to Quraish and Jurhum.

فأقسمتُ بالبيت الذي طاف حولَهُ رجالٌ بَنَوهُ من قريشٍ وجُرْهُم

This line refers to the essential ritual of the pilgrimage, which is the walk around the Kaabah, which everyone can see today on television screens. The Kaabah itself is referred to as the House, which was the traditional reference to it among the Arabs, and it is referred to in the same way in the Qur’an. The poet mentions that the Kaabah was built by men from Quraish and Jurhum. These are the names of two major Arabian tribes that lived in Makkah. Jurhum came first, shortly after Prophet Abraham settled there his young son Ishmael and his mother, Hagar. Jurhum continued to live in Makkah for several generations, then it was taken over by the Khuza’ah tribe, before it was finally taken over by the Quraish tribe. Quraish rebuilt the Kaabah a few years before Islam, because its building was severely damaged by torrential rain.

Al-Nabighah al-Dhubyani was another of the three top poets whose long poem was displayed on the walls of the Kaabah[5]. In his poem he mentions:

‘the travellers to Makkah’ and how pilgrims touch the Kaabah as they do their ritual walk around it. He also refers to the idols placed on it and the sacrifice used to be offered by the pagan Arabs to these idols. He swears by God whose Kaabah he himself has touched, and who has given safety to the birds which flock to the Kaabah, restraining the travellers to Makkah from hunting them on their approach. His oath is to refute the accusation levelled at him, that his love poetry was addressed to the wife of al-Nu’man, the King of Iraq.[6]

فلا لعَمْرُ الذي مسّـحـتُ كعبته وما هُريـق على الأنصـاب من جســد

والمؤمن العائذات الطير تمسحها ركبان مكة بين الغيل والســعـد

ما إن أتيتُ بشيء أنت تكرهه إذاً فلا رَفعتْ سوطي إليَّ يدي

These two famous poets died shortly before the start of the Islamic message. Al-Khansaa was another poet of the same era. She is famous for her many poems extolling the virtue of her killed brother, Sakhr. She excelled in that and she is considered the best woman poet of old times. Most of her poetry about her brother was before she embraced Islam, towards the end of the Prophet’s life. The contrast in her attitude is clearly seen in the fact that she lost her four sons in the Battle of Qadisiyyah, but she did not write a single poem about them, because she realized that they were martyrs for whom there should be no grief, while she continued to write about her brother feeling the old grief. In one of her poems about her brother, she starts by saying that her eyes continue to weep for Sakhr who was without peers. The fourth line mentions the Sanctified House, which is another common reference to the Kaabah in Arabic poetry, from many centuries before Islam to the present day.[7] She says:

I swear by the Lord of grey camels proceeding fast to the Sanctified House, their ultimate destination.

If the ꜤAmr clan are in grief for him; it is because they know that they lost their best

حلفْتُ بربّ صُهْبٍ مُعمِلات إلى البيتِ المحرّمِ منتهاها

لئِنْ جزعَتْ بنو عمروٍ عليه لقد رُزِئتْ بنو عمرو فتاها

Two Arabian tribes from Yemen, ꜤAkk and Midhḥaj, did not share in idol worship and continued to follow Abraham’s creed of monotheism. They had their delegation performing the pilgrimage every year. They declared their submission to God in rhyme. Addressing the holy city and appealing to it to reject the false believers. Unless this done, the Sacred House would be in ruin. We respond to God, having no doubt.[8]

يا مكةُ الفاجرَ مُكّي مَكا ولا تمُكي مذحجاً وعكّا

فيترك البيت الحرام دكا جئنا إلى ربك لا نشُكا

If we go further back in the history of Arabia and Makkah, we note that Jurhum were ejected out of Makkah because they perpetrated injustice in the holy city. History tells us that before they left Makkah, Jurhum buried the Black Stone and the two deer statues placed at the Kaabah in the well of Zamzam, which is adjacent to the Kaabah. They made sure that the location could not be determined. This they did for two reasons: the first is to make it difficult for the victorious tribe, Khuzaah, to live comfortably in Makkah and provide drinking water to the pilgrims, and to let pilgrims feel the effect of the event by missing the Black Stone. Zamzam remained blocked until Abd al-Muttalib, the Prophet’s grandfather, located it and re-dug the well that continues to provide drinking water for pilgrims until the present day.

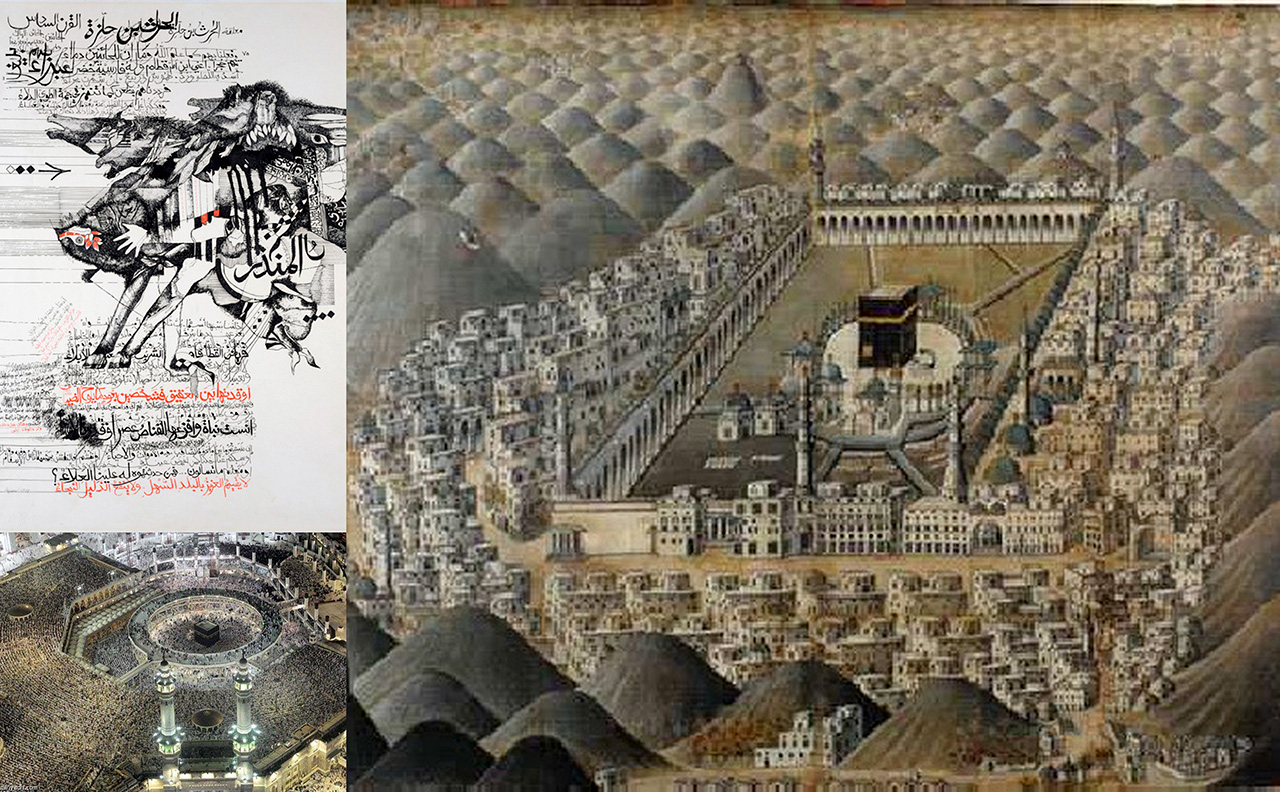

Figure 3. Early eighteenth-century painting from the Uppsala University collection, Sweden. Inv. No. UU2372 © Uppsala University Library. (Mols 2013: 120–121). Painting is by an unknown artist and appears to be the astonishingly exact drawing of Makkah and the Ka’ba in the years 1710–1712.

Jurhum were very sad to leave Makkah, and their chief at the time, Amr ibn al-Harith, expresses his grief in a poem in which he mentions al-Hajoon and al-Safa. Al-Hajoon is a district of Makkah about one and a half miles from the Sacred Mosque, while al-Safa is a hill very close to the Mosque where another ritual of the pilgrimage is started. He says in his poem:

A woman says with her tears flowing as they pour down from her eyes, grieving

That it looks as though we lost the friends we had between al-Hajoon and al-Safa, and as though our pleasant evenings in Makkah are gone for no return.[9]

وقائلة والدمع مبادر سُكْبٌ وقد شُرقت بالدمع منها المحاجر

كأنْ لمْ يكُنْ بين الحجون إلى الصفا أنيسٌ ولمْ يَسْمُرْ بمكة سامر

Quraish took over Makkah nearly two centuries before Islam, and it was Qusay ibn Kilab, the Prophet’s seventh ancestor, who was the first man from Quraish to become the undisputed master of the holy city. Quraish became the master tribe of the entire Arabia, benefiting by its position in Makkah, where they were good guardians of the Kaabah, facilitating the needs of the pilgrims in the pilgrimage season, and providing them with food and drinking water. They also had a long line of leaders who were keen to serve the community, enhance the position of the city and serve the pilgrims. They were also keen to maintain justice, because they felt that injustice must never be perpetrated in the holy city. The last of these leaders was Abu Talib, the Prophet’s uncle who protected him when he started to deliver the message of Islam, calling on people to worship the One God, the only Lord of the universe, instead of idolatry. The poetry of the period is rich with information about tasks connected with the pilgrimage, and who provided what service to the pilgrims. Makkah has frequently mentioned as also the places around it visited by the pilgrims to fulfil their ritual duties.

About twenty years before the message of Islam, the people of Quraish established an alliance between all clans living in Makkah, with the purpose of preventing injustice in Makkah, whether done to its people or to any visitor. The reason for making this alliance was that a pedlar came to Makkah and sold his goods to al-Aas ibn Wail, one of its noblemen, but the nobleman did not pay him the price. When his repeated attempts to secure his right ended in failure, the man stood at a hill close to the city at sunrise and shouted his appeal to the people of Makkah for support. He made his appeal in three lines of poetry, addressing them as Fihr’s descendants. Fihr was one of their very early ancestors.

O Fihr’s descendants, a wronged person appeals to you as his merchandise has been taken in the midst of Makkah. He is far away from home, having come in consecration, but has not yet fulfilled his umrah [i.e. mini-pilgrimage].[10]

يا آل فهر لمظلوم بضاعته ببطن مكة نائي الدار والنفر

ومحرم أشعث لم يقض عمرته يا للرجال وبين الحِجْرِ والحَجَر

إن الحرام لمن تمت كرامته لا حرام لثوب الفاجر الغُدَر

When the people ascertained what happened to the pedlar, they supported him and forced his buyer to pay him in full. They then concluded their alliance which was proposed by al-Zubayr ibn Abd al-Muttalib, the Prophet’s uncle. Over thirty years later, when the Prophet was in Madinah, he mentioned this alliance, praised it saying: ‘I attended at Abdullah ibn Judaan’s home the conclusion of an alliance, which I would not barter for anything in the world. If I am today appealed to under this alliance, I will honour it’. Thus, the Prophet confirmed that he would honour his pledge, made long before Islam, since it fits with the Islamic principle of removing injustice.

Al-Zubayr, the Prophet’s uncle, praised this alliance and mentioned its purpose in two lines of poetry:

The honourable people pledged and agreed that no unjust person shall reside in Makkah.

To this they concluded their covenant that neighbours and visitors are safe in their city.[11]

إن الفضول تحالفوا، وتعاقدوا أن لا يقيم ببطن مكة ظالمُ

أمرٌ عليهِ تعاهدوا، وتواثـقـوا فالجارُ والمُعْتـرُّ فيهم سـالمُ

There are several events when this alliance was immediately honoured by the noblemen of Makkah. No one need suffer injustice in the city, and they were ready to fight for any victim, regardless of his position or the nobility of the one who is wronging him.

During the Prophet’s message, we have a wealth of poems mentioning Makkah and its areas. One long poem relates to the early period of Islam, when the people of Makkah firmly rejected the message and started to show hostility to the Prophet and his followers. Abu Talib, his uncle, called on the people of his clan to stand up to the rest of Quraish and they responded positively. He wrote a long, powerful poem, highlighting the sanctity of the Kaabah and the city of Makkah, praising his clan for their firm stand and speaking well of the dignitaries of Makkah saying that they would not allow injustice to be perpetrated against its own people.

The Prophet spent the first thirteen years of his message in Makkah calling on its people to believe in Islam, but he was met with determined opposition. He then moved to Madinah where he established the first Muslim state. During his ten years there, there were several encounters with the people of Quraish in Makkah, including two main battles. Concurrently, there was a ‘media’ confrontation, with poetry being the main weapon. Poets from Makkah, like Kaab ibn Zuhair and Abdullah ibn al-Zibaara abused Islam and the Prophet, and Muslim poets like Hassan ibn Thabit and Abdullah ibn Rawahah defended him. The poems are well documented and there is frequent mention of Makkah, the Kaabah, the Mosque and the areas around it.

Poetry of the next era has a wealth of poems that mention the pilgrimage to Makkah and the poets’ experience on their trips and during their stay in Makkah and its surroundings. Examples can be quoted in plenty, but the purpose of this article is mainly to show that Makkah, the Kaabah and the pilgrimage feature prominently in Arabic poetry in pre-Islamic days, during the 23 years of the Prophet’s delivery of the message of Islam, and in the very early days of Islam.

Figure 4. An arial view of millions praying around Kaabah

[1] Simon O’Meara, “The Ka’ba Orientations: Readings in Islam’s Ancient House”, Edinburgh Uni Press, 2020

[2] The Muallaqat for Millennials, Pre-Islamic Arabic Odes, Published by King Abdulaziz Center for World Culture (Ithra) an initiative by Saudi Aramco, 1st edition, 2020

[3] Zuhayr ibn Abī Sulmā Arab poet, Encyclopaedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Zuhayr-ibn-Abi-Sulma. Accessed 22- 01-2021

[4] H. al-Zawzanī (died 486 AH 1093CE), Sharḥ al-MuꜤallaqat al-SabꜤ, [Explanation of the Seven Displayed Poems], Dar Ihyā’ al-Turath al-Arabi, 2002, Vol. 1, p. 139. Also, J. al-Zamakhshari, (died 583 AH, 1187 CE), Rabi al-Abrar wa Nusoos al-Akhyar, Beirut, Mu’assasat al-Alami, 1992, Vol. 5, p. 304

[5] Ziyād ibn Muʿāwiyah al-Nābighah al-Dhubyānī, al-Nābighah Arab Poet, Encyclopaedia Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/biography/al-Nabighah-al-Dhubyani. Accessed 21-01-2021

[6] A. al-Dainoori, (died 276 AH, 890 CE), al-ShiꜤr wal-ShuꜤaraa, [Poetry and poets], Dar al-Hadith, Cairo, 2010, Vol. 1, p. 166.

[7] Ibn ꜤAbd Rabbih, (died 328 AH, 940 CE), al-ꜤIqd al-Farīd, [The unique necklace], Dar al-Kutub al-Ilmiyyah, Beirut, 1984, Vol. 3, p. 226

[8] Emile Yaaqoob, al-MuꜤjam al-Mufassal fi Shawahid al-Arabiyyah, [Dictionary of Arabic patterns], Dar al-Kutub al-Ilmiyyah, Beirut, Vol. 11, p. 257.

[9] A. al-Suhaylī, al-Rawḍ al-Unuf, Dar al-Fikr, Beirut, Vol. 1, p. 137

[10] A. al-Suhayli, ibid, Vol. 1, p. 156

[11] Al-Suhayli, ibid, Vol. 1, p. 157.

4.5 / 5. Votes 2

No votes so far! Be the first to rate this post.

Muslim Heritage:

Send us your e-mail address to be informed about our work.

This Website MuslimHeritage.com is owned by FSTC Ltd and managed by the Foundation for Science, Technology and Civilisation, UK (FSTCUK), a British charity number 1158509.

© Copyright FSTC Ltd 2002-2020. All Rights Reserved.