An insight into the influence of Muslims on the musical revival of Europe which can be detected as early as the period of the Carolingian Empire.

Extracted from the full article:

The Arab Contribution to Music of the Western World by Rabah Saoud

The influence of Muslims on the musical revival of Europe can be detected as early as the period of the Carolingian Empire. Charlemagne tried to emulate and compete with Baghdad and Cordoba. He too invited scholars from abroad to his court and established schools[1]. This revival was chiefly mastered by three influential scholars; Theodolfus (d.821), Claudius (d.c.839) and Agobardus (d.840), all of whom had contacts with Muslim learning as they were Goths born or educated in Spain or Southern France. In addition to his friendship with the Abbassid Caliph, Harun Al-Rashid, the renowned Chanson de Geste revealed that Charlemagne spent seven years in Spain[2].

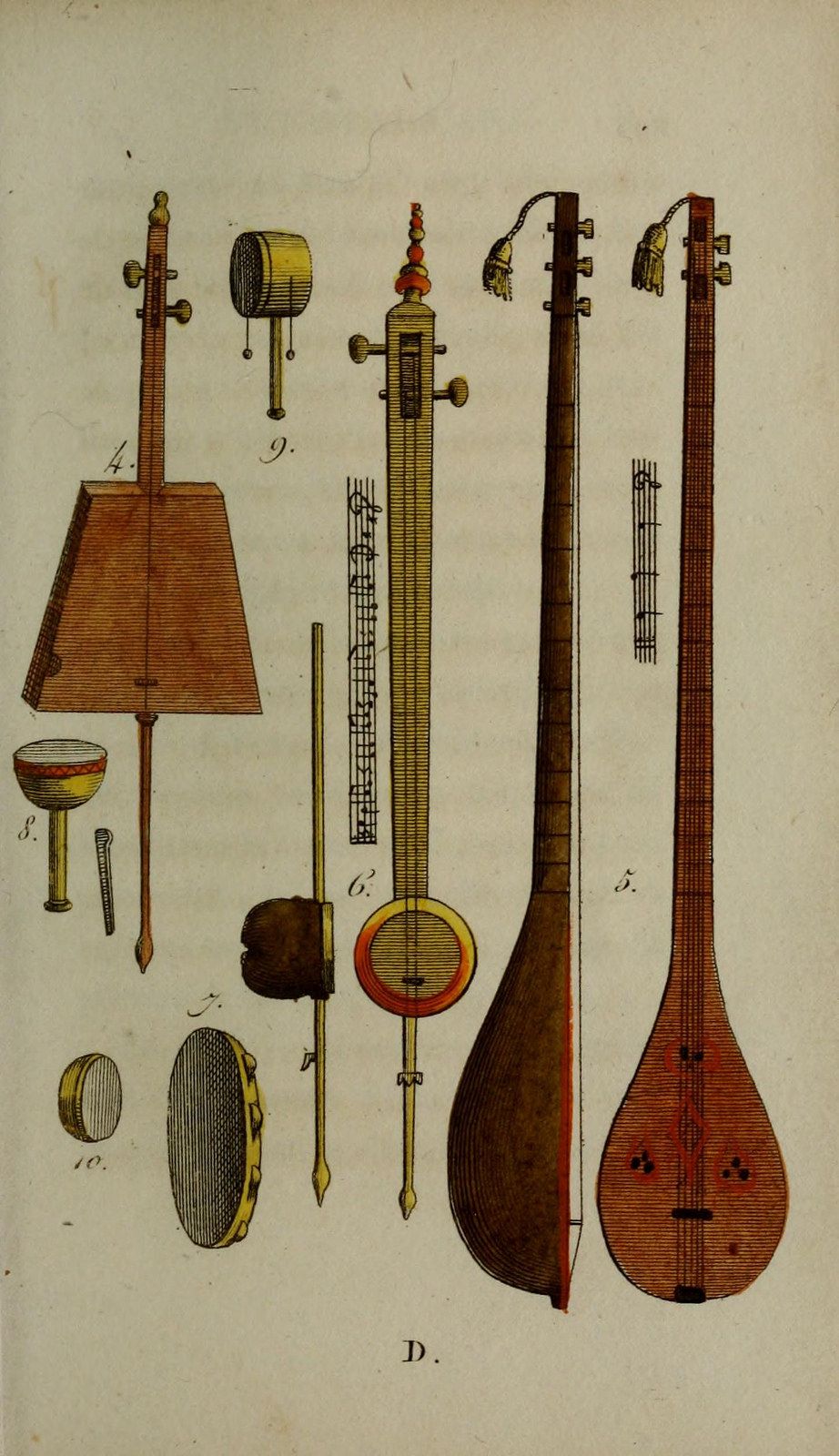

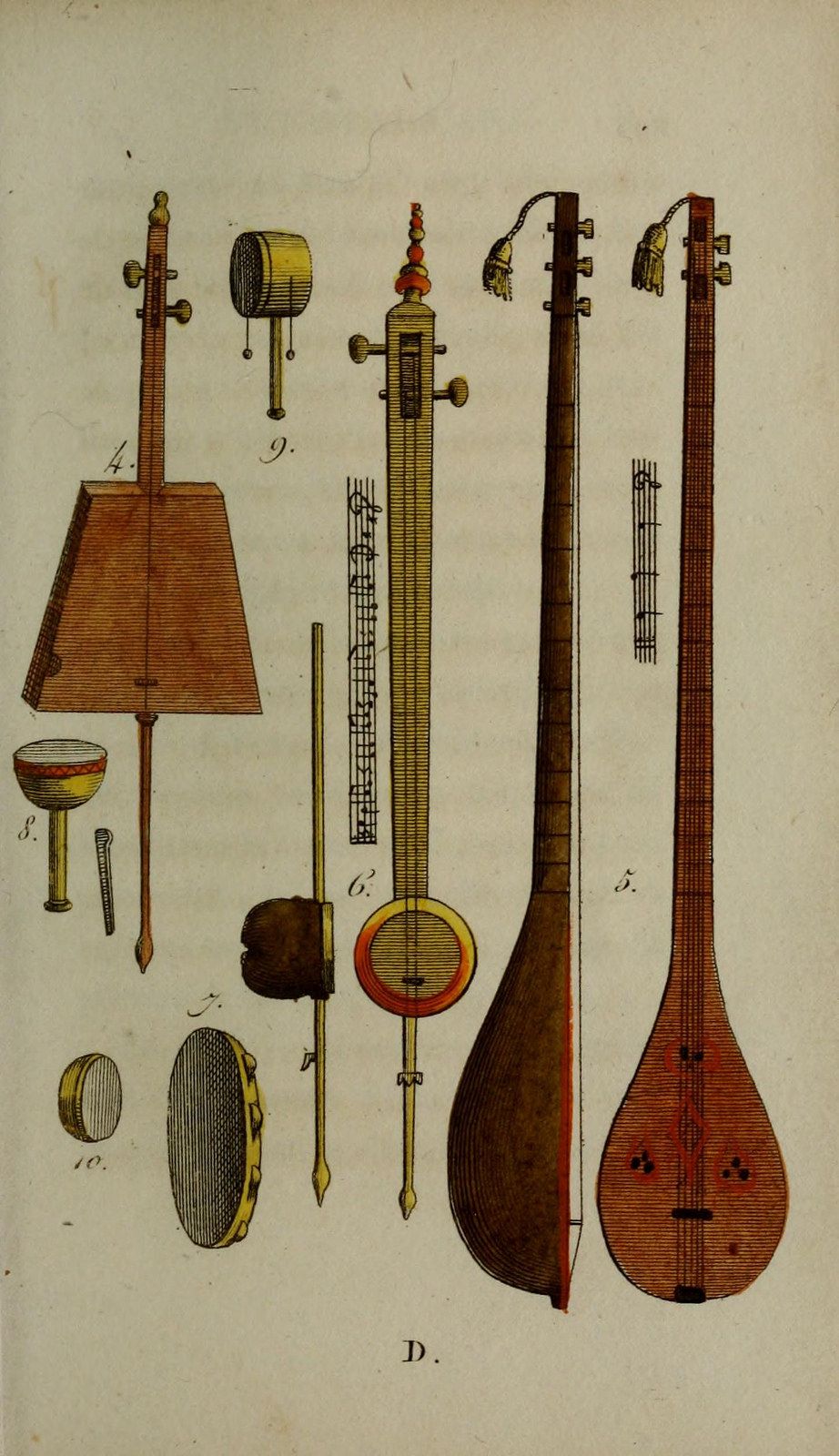

According to some sources[3], Pepin and Charlemagne (9th century) expanded, to some extent, the use of church music through the introduction of some Muslim Arabic instruments. Schlesinger[4] is certain that these instruments came from Spain or Sicily. She pointed out that the instruments portrayed in the Evangelarium of St. Medard (8th century) and the Lothair, Aureum and Labeo Notker Psalters (9th & 10th centuries) were all Oriental instruments derived from the Egyptian or older Asiatic civilisation and disseminated in Europe mainly through the Muslims. Notwithstanding, by the eleventh century the flow of Muslim knowledge, including music, reached its apogee. The musical transfer was carried out through three main routes.

Spain and the Southern France Connection:

The social and economic intercourse between Spanish Christians and Muslims and other European Christians resulted in the dissemination of Islamic learning and art throughout Europe. The influence of Muslim music in Spanish and Portuguese music and folklore is self evident and does not need any proof. There is a considerable amount of literature on this issue confirming the deep penetration, which shaped the cultural and artistic life of these two regions under the 800 years of Muslim rule. Perhaps the earliest example of this influence is found in the collection of Cantigas de Santa María. Composed around 1252 under the orders of Alfonso X el Sabio, king of Castile and Leon, the collection consists of 415 religious songs. These songs are the first known literature works, preserved with their original musical notation, in the Galician language. Detailed studies[5] on their structure and form have concluded that they were a direct inspiration of Arabic music as 335 of them were Zajal. Chase[6] has found that the melodic patterns in the Cantigas closely follow the forms of the French styles Virelai and Rondeau. Apel[7] linked the virelai to a Spanish (Andalusian) origin, while Plenckers[8] proved it to be inspired by songs known as Al-Muwashahat. Guettat[9] found the poetical form of muwashahat and Zajal in a large number of the Ballades and Rondeau styles dated from the thirteenth century and coming from the north of France such as “the beautiful Aeliz” in the Robin & Marion play of Adam le Bossu (13th century).

Similar conclusions can be made about the Cantigas de Amigo; the Cancionero de Palacio and the Chansonnier of the Arsenal[10] (Saint Germain des Pres). In fact, the consensus of Western academics believe that the explanation of the appearance of Zajal in the West can only be attributed to the Andalusian Muwashah, which, in the view of some experts, itself originated from an ancient Roman poem with a similar structure. The latter claim has never been substantiated though Arabs have always been renowned for their poetical talents and literary inventions.

Another area where Muslim influence was early felt was in the popular poetry of the Troubadours. These medieval lyric poets, musicians or singers spread mainly in the Languedoc region in the south of France, as well as in the north of Spain and Italy. There is a growing body of evidence that troubadours were influenced by Andalusian poetry and music. The evidence taken from the poetry of Guillaume IX of Poitiers (1071-1127), a renowned provencial troubadour, is quite clear. In his study, Levi-Provencal is said to have found four Arabo-Hispanic verses nearly or completely recopied in Guillaume’s manuscript[11]. The contact with Christians, in this subject, was established through the many thousands of Muslim prisoners, including women and young girls, who were taken to Normandie, Bourgogne, Provence, Aquitaine and Italy, especially after the fall of Balbastro. According to historic sources, Guillaume VIII, the father of the troubadour Guillaume IX, brought to Poitiers hundreds of Muslim prisoners[12]. It is likely that Guillaume IX learnt much from some of these prisoners whom his father kept as servants. Pope Alexander II, is also known to have brought to Italy more than a thousand Muslim women[13]. Trend[14] admitted that the troubadours derived their sense of form and even the subject matter of their poetry from the Andalusian Muslims.

The troubadours integrated Andalusian themes such as chaste and virtuous love and the idealisation of women into European poetry. Such noble themes could not be found in Western poetry before the Andalusian mode[15]. Nelli[16] admitted that people of tenth century Europe, especially Provence, learnt from the Arabs new kinds of affectionate and compassionate pleasures and love, contrary to the customs of robbing, raping and massacring which swept the rest of Europe in those times. He summed it up when he wrote: ‘‘we owe to the Orient and the Moors of Spain all what is noble in our customs.‘

In fact the influence of Andalusian themes and poetry had an even more significant impact, paving the way for changing attitudes and morals which were the fundamental seeds of the Renaissance[17]. Islam, father of monotheism, which itself prevails in the Christian doctrine, fought the polytheism which had existed before and took clear positions against the changing essence of Christianity, which replaced the sole God with intermediary levels of ranks of saints and clergy. This monotheism was the fundamental spirit of Catharism[18] and later the free spirit[19], which spread along southern European territory adjoining the Muslim Caliphate. The majority of the Troubadours, imitating Iberian musicians, believed in Catharism. Maria, Mary, (Peace be upon her) became the true object of the songs and poetry of the Spanish and French Troubadours as well as the Italian “Trovatori”. The Cantigas songs provided an excellent example of refined court music, completely detached from the liturgy. Later, they carried a spiritual message of revival, addressing directly the people, in a period of violent political struggles and distrust in the corrupt clergy. This is the period when the Lauds[20], a composition of songs in praise of God, appeared reaching their apex in the thirteenth century. From this time evidence of the influence of muwashahat and Zajle has been found, namely in the lauds of the Franciscan Jacopone da Todi (13th century) and in a large number of frottola and other Italian songs of the fourteenth and up to sixteenth centuries. Guettat[21] and more recently Pacholczyk[22] have demonstrated the influence of the Nawba[23] (also spelt Nuba) musical system of Morocco on the Music of the Troubadours and Trouvères. Until recently, the rhythms of the Nawba, with their five movements and their semitones continue to influence European composers. We have the example of the Camille Saint Saëns (1835-1921), French composer and co-founder[24] of the Société Nationale de Musique (1874), who employed North African and Andalusian scenes and themes in many of his compositions, as for example in his opera «Samson and Delilah» (1868) and in «Suite Algerian» (1879).

The Spanish connection played another role by extending Muslim influence to the new world starting with Latin America. The migration of the Moriscos to Latin America transported their Andalusian knowledge and arts, including music, to that continent. Integrating with local traditions and rhythms, Zeriyab’s music and melodies gave rise to a number of distinguished Latin American musical styles and dance rhythms such as the Jarabe[25] of Mexico, la Cueca and la Tonada of Chile, El-Gato, El-Escondido, El-Pericon, la Milonga and la Chacarera which spread to Argentina and Uruguay, la Samba and la Baiao[26] in Brazil, la Guajira and la Danzón of Cuba[27]. Many of these musical styles had a flamenco origin which is renowned for its Arabic connection. According to Blas Infante[28], flamenco originates from the Arabian word ‘fellah-mengu’, a composite word used to describe a group of rural wanderers. The thesis is that

when the Moriscos, most of whom were farmers, were expelled from their homes in order to avoid death, persecution or forced deportation, they took refuge among the Gypsies becoming fellahmengu. Posing as Gypsies they managed to return to their cultural practices and ceremonies including the singing.

According to Infante, that is how flamenco began to germinate[29].

[1] Campbell, D. (1926) Arabian Medicine in the Middle Ages’, vol.1, 111-12.

[2] and claimed that he invaded Arabia.

[3] Schlesinger, Kathleen (1910) The Instruments of the Modern Orchestra: Vol. 1 Modern Orchesteral Instruments; Vol. 2 The Precursors of the Violin Family, Charles Schribner, New York. p.329, 342,371,374,398, 399,420.

[4] Ibid..

[5] Ribera, Julian (1970), ‘Music in ancient Arabia and Spain : being La Música de las Cuntigas’. Da Capo, New York.

[6] Chase, Gilbert (1941), ‘The Music of Spain’. W.W Norton and Co, New York.

[7] Apel, Willi (1954), ‘Rondeaux, Virelais, and Ballades in French 13th-Century Song’, Journal of the American Musicological Society, 7, pp. 121-30.

[8] Plenckers, Leo J. (1982), ‘Les rapports entre le muwashshah algérien et le virelai du moyen âge’, I. A. El-Sheikh, C. A. Van de Koppel e R. Peters (eds.), The Challenge of the Middle East: Middle Eastern Studies at the University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam: University of Amsterdam, pp. 91-111;

[9] Guettat, M. (1980), ‘La Musique classique du Maghreb’, Sindbad, Paris.

[10] Ibid, p.159.

[11] Guettat (1980) op.cit., p.150.

[12] Hunke, S. (1969), ‘Shams al-‘Arab Tasta’a ‘ala Al-Gharb’, 2nd edition, Commercial Office publishing, Beirut.

[13] ibid.

[14]Trend, J.B (1965), ‘Music of Spanish History to 1600′, Krause Reprint Corp, New York.

[15] Chailley, J.; (1969), ‘Histoire musicale du Moyen Age’, 2nd edition, Presses universitaires de France,

Paris.

[16] Nelli, René, (1974) ‘L’Erotique des troubadours. Contribution ethno-sociologique à l’étude des origines sociales du sentiment et de l’idée d’amour’, published thèsis, 11th edition, 2 vols. Privat, Paris.

[17] Scott S.P. (1904) ‘History of the Moorish Empire’, 3 volumes, The Lippincot Company, Philadelphia.

[18] Catharism claims to return to the purity of the first Christians rejecting the Church disorders which arouse a spiritual confusion among people. This new sect, spread in 12th century, preached anticlerical evangelism rebelling against Rome’s power. Its followers stretched along the southern borders of Europe adjoining the Islamic Caliphate to the South of France, North of Spain and North East of Italy encompassing the provinces of Languedoc, Aquitain, Gasconha, Auvergne, Lemosin, Delfinat, Catalonia and Vals Alpins Italians. Such area received considerable influx of Muslim influence appearing not only in cultural context but also in architecture and arts. The crusade against the Cathars (also known as the Albigeses) preached by pope Innocent III against them lasted from 1209 to 1229.

[19] Spread in Europe in 1300s under the influence of the Muslim sufis. Among its famous members, included Marguerite Porete, burned at the stake in Paris in 1311 and Heinrich Suso (Germany).

[20] The word Lauds (i.e. praises) explains the particular character of this office, the end of which is to praise God. All the Canonical Hours have, of course, the same object, but Lauds may be said to have this characteristic par excellence. The name is certainly derived from the three last psalms in the office (148, 149, 150), in all of which the word laudate is repeated frequently, and to such an extent that originally the word Lauds designated not, as it does nowadays, the whole office, but only the end, that is to say, these three psalms with the conclusion. (see https://www.newadvent.org/cathen/09038a.htm).

[21] Guettat, (1980), op., cit.pp.145-159.

[22] Pacholczyk, Jozef M. “The Relationship Between the Nawba of Morocco and the Music of the troubadours and Trouvères”, in The World of Music, 25 (1983), pp. 5-16.

[23] Nuba (plural nubat or nawbat): a two-part “musical suite” in a single mode or maqam. Thirteen nubat make up the core of the Tunisian maluf. (further definitions of musical instruments and terms can be obtained from the excellent site website: https://www.turath.org/ProfilesMenu.htm).

[24] With Massenet and Bizet.

[25] Translated as syrup in English which refers to Sharab in Arabic.

[26] Baiao music of Brazil which originates from Arab modal melodies about the home land brought by the Portuguese and Spanish colonisers to Latin America, initially popular among the poor but later became popular (https://www.iaje.org/pdf/12003toronto_neto.handout.pdf).

[27] Evora Tony (1997), ‘Origins of the Cuban music’, Alliance, Madrid, , p.38.

[28] Blas Infante (1980) “Orígenes de lo flamenco y secreto del cante jondo”,, Junta de Andalucía, Seville.

[29] For more on Latin America see our forthcoming articles. Also Lutfi A. A (1964), ‘The epic one Arab and its influence in the Spaniard’, Santiago of Chile and Francisco F.M. (1971), ‘narrative Poetry Arab and epic hispanic’, Gredos, Madrid.

4.8 / 5. Votes 160

No votes so far! Be the first to rate this post.

Muslim Heritage:

Send us your e-mail address to be informed about our work.

This Website MuslimHeritage.com is owned by FSTC Ltd and managed by the Foundation for Science, Technology and Civilisation, UK (FSTCUK), a British charity number 1158509.

© Copyright FSTC Ltd 2002-2020. All Rights Reserved.