Turkish cuisine is largely the heritage of Ottoman cuisine, which can be described as a fusion and refinement of Central Asian, Middle Eastern and Balkan cuisines. Turkish cuisine also influenced these cuisines and other neighbouring cuisines, as well as western European cuisines. The Ottomans fused various culinary traditions of their realm with influences from Middle Eastern cuisines, along with traditional Turkic elements from Central Asia such as yogurt. The following article reviews a book containing a collection of papers on the history of Turkish cuisine in the writings of some prominent historians of gastronomy, with a focus on the Ottoman palace and civil cuisine traditions and recipes.

Arif Bilgin* and Özge Samanci**

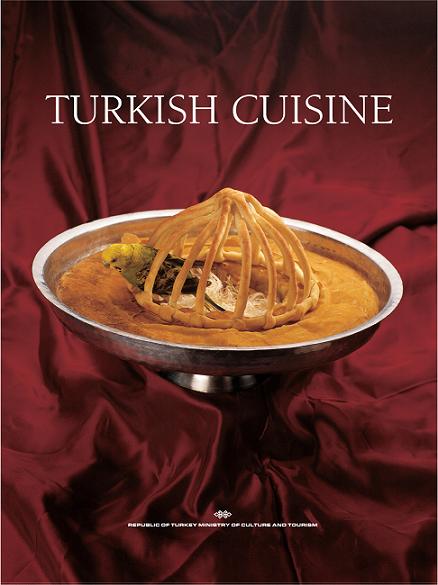

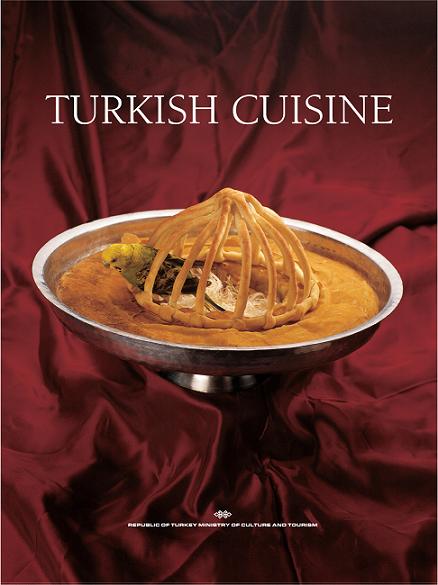

Book Review of Turkish Cuisine, edited by Arif Bilgin and Özge Samanci. Original Turkish title: Türk Mutaǧi. English version translated and edited by Cumhur Oranci et al. Photos by Ahmet Bilal Arslan and İsmail Küçük. Ankara: Ministry of Culture and Tourism, 2008, 392 pp. (Series: “Ministry of Culture and Tourism publications”, 3167; “Art Series of General Directorate of Libraries and publications”, 477).

Turkish cuisine developed new characteristics with the migration of peoples from Central Asia, which started in the 10th century; during the Ottoman period, it was influenced by various kitchen cultures from these areas and it, in turn, had an influence on them. With the Ottomans, Turkish cuisine was no longer limited to the monotype diet model as it was in Central Asia and likewise; it was not dominated by the local practices in the areas where the Turks migrated. During the Ottoman period, Turkish culinary culture got a very new structure with more balanced consumption of animal products and grains. It took its own place as an original model between two worlds, dominated in the Far East with rice and in Europe with wheat and meat.

|

|

Figure 1: The cover page of the book Turkish Cuisine, edited by Arif Bilgin and Özge Samanci (Ankara, 2008). |

When we look at the historical journey of the Turkish kitchen, we can say that the Central Asian Turkish kitchen was fairly plain and was limited in terms of menu. It appears however that migrations lead to fundamental changes and a gradual enriching of their kitchen. Items adopted from the Arabian and Persian cultures clearly show this fact. What is obvious today is that the actual enrichment in Turkish cuisine was inherited from the Ottomans. With the features adopted from Seljuk, Arab and Persian cultures, Turkish culinary culture began to be enriched by the existing Anatolian culinary culture and the staple products belonging to the area. At the same time, the Ottoman Palace tradition contributed greatly to the diversification and enhancement of the culinary culture. It is obvious that these transitions did not take place in a short space of time but over a long period.

Another transition process took place: it was after the discovery of the Americas. People of Anatolia began to get acquainted with products like tomatoes, beans, green peppers, and corn after the 17th and 18th centuries. These food stuffs that were introduced over a period of several centuries caused revolutionary culinary transitions in the long run. As a result of the start of the modernization period, culinary culture pertaining to Ottoman cities started to change in both dinner customs and ingredients used in the preparation of the meals. These changes within the Turkish kitchen continued throughout the 20th century. By the second half of the century, as part of a globalization process in the world, ready-made food products started to take place in Turkish kitchens and their consumption increased gradually. New dining trends such as fast food became widespread while at the same time rural-urban migration accelerated. As a result of these factors, the transition of Turkish culinary culture continued in both urban and rural areas.

This book contains five chapters in accordance with the historical process mentioned briefly above. The first chapter is devoted to the culinary culture from Central Asia as a foundation of the Ottoman kitchen. Mehmet Alpargu describes the kitchen of Central Asian Turks. Greatly affected by the climatic conditions of the region, Turks in Central Asia lived mostly on meat and milk products. Cereal crops were considered “supporting products” and were consumed in lesser quantities. In fact Turks really only began to consume grain products in significant quantities after they took up a more settled existence. Alpargu talks about the drinking culture of the Turks and explains the place of mare’s milk (kimiz), buttermilk and beverages, with or without alcohol, explaining many aspects in details, e.g. from the production of kimiz to its presentation.

|

|

Figure 2: A banquet given by the commander-in-chief Lala Mustafa Pasha to the janissaries in Izmit, 5 April 1578. Topkapi Palace Museum Library, MS H1365, fol. 34b. |

Chapter two includes three articles that discuss the transition of Turkish culinary culture with the migrations towards the West. The first of these articles is Altan Çetin’s, which argues that the Seljuk kitchen was from the Karakhanid and Mamluk periods. According to Çetin, Turks migrated through regions that were cultivating cereal crops alongside animal products. He points out that the Turks’ meat eating practices started to change after these migrations, greatly affected by the dominant cultures of the region. Research supports this and it is possible to see some references to abundant cereal crops alongside animal products. However, this diversity is only observed in a few sources and thus it is almost impossible to determine how widespread this diversity was among ordinary people. On the other hand, Mamluk culinary culture did not leave the borders of Karakhanid-Seljuk, and showed a remarkable similarity. The author explains this case, pointing out the fact that culinary culture does not acknowledge political borders that it is mostly related to history and geography.

The article by Haşim Şahin contains more concrete information regarding the transition that came with the migrations. Haşim Şahin delves into the culinary culture of the Seljuks together along with addressing subjects such as agriculture, husbandry and Sufi belief. He argues that advantages presented in the Anatolian geography to the immigrant added a great opulence to the Seljuk kitchen. The various sources used by the author reinforce and enrich our knowledge of the period. The article includes interesting information such as the names of animal and vegetables dishes, sometimes the ways of cooking them, and mystical understanding of the period. As we discover from the article of Şahin, the Ottomans’ balanced diet of both animal and vegetable products was learned from the times of the Seljuks.

Nicolas Trépanier looks into the 14th-century culinary culture, a period where only limited information is available. This article might be considered as a summary of the author’s doctorate dissertation and is based mostly on hagiographies. He emphasizes that in 14th-century Anatolia, meat and especially mutton was available in abundance and this glut of animals made other animal products, especially milk, easy to obtain. From this article, we learn that in the Anatolian era fruit was so plentiful that the excess was exported to other regions. Regarding drinks, we learn that sherbet, cülab and a sort of boza called fuqâ were also consumed in large amounts. The other factor that Trépanier points out in the drinking culture of the Anatolian Turks is the absence of hot drinks, which were predominant in the Byzantine culture. The author presents this fact as an important difference between the two cultures. Trépanier gives a special significance to halva and rice. In fact, these two foods had become the two most important items in the Ottoman cuisine. The interesting point is that Trépanier attributes a religious significance to halva for whatever purpose it was eaten. This might have something to do with the nature of the sources he used, because in subsequent centuries halva would become a food of enjoyment (for instance halva ‘chit-chatting’).

|

|

Figure 3: Miniature depicting Sultan Ahmed III and his public officials during a banquet. Source: Levnî, Surnâme, Topkapi Palace Museum Library, A 3593. |

The second chapter, where the classical Ottoman kitchen is explored, consists of three sections. In the first section, four articles examine palace, festivals and soup kitchens.

In his article, Arif Bilgin studies the palace kitchen during the classical period (15th to 17th centuries) which he considers as the peak of Ottoman cuisine. Bilgin presents his subject in the context of organizing, provisioning and culinary culture. The author claims that the palace kitchen “Matbah-i Amire” organization, which was established during the reign of Sultan Mehmed II (1451-1481), gained maturity as the state developed. Indeed, within the kitchen organization, units like the halva kitchen, tinning workshops and some sections within other service groups emerged in the 16th century. The author describes the palace culinary culture as a product of a continuum that in part maintained habits brought from Central Asia that were developed in the Near East, before evolving fully in Anatolia.

Ottoman festivals, parades, various shows and entertainment are important in terms of the banquets that were organized alongside them. Günay Kut, explores this side of festivals and festival feast tables. In her article, she studies surnames relating to 1582, 1675, 1720 and 1834 circumcision feasts as well as sources describing circumcision feasts that Sultan Mehmed II organized for his sons Bayezid and Mehmed and those of Suleiman I organized for his sons Bayezid and Cihangir. In her article, Kut utilizes only a few of the many surname available, however these surnames are unique sources from which we can learn lists of the menus consumed at the festivals. Apart from the food and drinks present at the table, Kut explores also the supply of food for festive banquets and also kitchenware gifts given by guests during the festivities. For example in 1834, during the wedding party of Saliha Sultan, there was an unprecedented serving of ice cream and drink to the guests; this treat could be considered as an indicator of a transition in festivity traditions.

Soup kitchens (İmarethane), which operated within the foundations established by Ottoman sultans or their close relatives, are important institutes for providing insights into Ottoman culinary history. Serving hot meals to the destitute, to those arriving from the provinces and to travellers, these ledgers from these establishments provide a great deal of information regarding meals cooked in their kitchens. With her valuable study, Suraiya Faroqhi presents a great deal of information about meals cooked and sweets distributed to people during religious festivities at the following almshouses: Sultan Selim II Foundation in Konya during the 16th and 17th centuries, Hatuniye İmarets in Trabzon and Tokat and Anatolian almshouses that were built by Amasya-based foundations during the reign of Bayezid II. Until this paper, most research into the culinary culture focused on Istanbul and on the Ottoman Palace, therefore Faroqhi’s study opens a unique window to Anatolia during the Ottoman period.

|

|

Figure 4: Ottoman spice makers-salesman ceremony during a festival. Source: Levnî, Surnâme, Topkapi Palace Museum Library, A 3593. |

The final article of this chapter is about the halva kitchen and halva culture. Although Trépanier attributes halva consumption in 14th century Anatolia to religious reasons, according to Ömür Tufan, halva in Ottoman society was related to sharing joy. In his article, Tufan relates how halva presentation developed its own impressive culture and how significant halva ‘chit-chatting (helva sohbetleri)’ became during the parties given in honour of the birth of children of the Sultan and for the accession to the throne. The author provides a list of types of halva cooked in the elite circles from the 15th to the 19th century. In fact, all these lists show the richness and extent of halva culture in Ottoman society. Certainly, this culture existed at the high levels within the palace and thus the place where the best halva was produced was the palace halva kitchen.

The second section of Part Two is devoted to the relationship between health, diet and honey. Nil Sari has contributed to this project with her article “Food as Medicine” about the central role of foods in Ottoman medicine and the humoral theory on which this was based. Sari also discusses foods used specifically as medicines and gives examples of treating ailments with foods and beverages. Fascinating extracts from early 20th century prescriptions written by palace physicians are a striking illustration of the importance attached to diet in Ottoman medicine.

Nuran Yildirim also writes about the relationship between health and eating for the Ottomans. From the point of view of four medical books, the author wrote an original work on cooking special diets to cure sicknesses with recipes for soups, main dishes and sweets (or desserts). From Yildirim’s list we can learn, for instance, which soup was used to treat which sickness, at which stage and how much should be provided. Moreover, the medical manuscripts she used are useful in terms of cooking history as they contain a number and variety of recipes.

Honey production and consumption in the Ottoman period is a less popular researched field mainly due to the limited number of references and information being dispersed across many sources. Ümit Ekin, in his study on this difficult subject, calculates honey production of some provinces during the classical Ottoman period. He also locates areas where honey was consumed. Used as a food, it was consumed as a sweetener and also used in medicines. Honey was mostly consumed in locations where it was produced, and larger cities and palaces shipped it from Moldavia, Wallachia and from other provinces within the Empire. The author, from the viewpoint of prices, finds out that the domination of honey over sugar continued until the 19th century when sugar beet production began.

The last article of chapter two where the classical period of Ottoman cuisine is described concerns the symbolic relation between food and power. In his article entitled “The symbolism of food: Tokens of political power and status, legitimization and obedience and challenging of authority”, Artun Ünsal describes in rich detail how food was utilized by the political authorities to reinforce their own power. He refers to the Eastern Turks who dominated Central Asia in the 8th century right through to the Ottomans who formed an empire in Asia Minor in the 14th century that lasted 600 years. Public banquets thrown by the khan or sultan are the most distinctive examples of how food was utilized by authorities to reinforce/legalize their power. As mentioned by the writer, the utilization of food as a means of politics did not just pertain to Turkish culture but was a common practice of all cultures and all times and still exists in the world today.

Chapter Three of the book takes a look at transitions that took place in Turkish cuisine from the 19th century to the present time. In this chapter, 19th century Ottoman Palace culinary culture and Istanbul cuisine, which mirrors it, are described by Özge Samanci. In her article, written after studying ledgers of the palace kitchens and cook books printed in Arabic Turkish script, Samanci deals with the culinary culture that formed in the 19th century Ottoman palace and within its circles. She includes details on the structure of the kitchens and kitchen personnel along with information on food items and types of dishes. In her article, she studies the widespread use of foods of American origin such as tomatoes, beans and potatoes in the kitchens and the implementation of European table manners and cooking of European style dishes among the 19th century Ottoman elite. Her article is important in that it deals with the most revolutionary period in Turkish cuisine.

Cuisines belonging to non-Muslim communities, which represent a large proportion of the whole population in the Ottoman Empire, is a subject that arouses curiosity. In her article “Rum (Greek) cuisine in the Ottoman period”, Marianna Yerasimos examines community cuisines and their differences and similarities to Muslim cuisine from the perspective of the Rum community. Instead of a homogenous Rum kitchen, Yerasimos appropriately prefers to use types of Rum kitchens showing differences according to their location and social status. She describes, with examples, food restrictions in the Orthodox religion and how these restrictions became a common denominator within the Rum community. In the article, she explains in detail the consumption of seafood, vegetables, herbs and vegetable oils during the Lent period, when animal products were restricted.

The next section of the book explores changes that took place during the last period of Ottoman cuisine. In order to illustrate these changes stories of olive oil and tea which became popular items in the 19th century Turkish kitchen were used. In his article, Faruk Doǧan explains in detail Ottoman olive oil production, giving examples from the last century and pointing out that up until the 19th century olive oil was used more in lighting and soap making than in cooking. The author indicates that on Ottoman soil olive oil consumption was mostly within the Rum population’s kitchen practices and this reminds us of the article by Yerasimos where restrictions during Lent contributed to an increased vegetable oil consumption.

In Turkish culinary culture, tea is as important as the food dishes, and Kemalettin Kuzucu describes the history of tea in the Ottomans. The author tells of how tea became a widely consumed item after the second half of the 19th century. At first tea was a curative drink and gradually became a popular drink with the Ottomans. Turks migrating from Central Asia and the Caucasus originally brought it to Anatolia in the 19th century, and this is one of the important facts to appear in this chapter. The author also accepts that due to the fashionable European lifestyle, tea was accepted in cities like Istanbul and also notes that agricultural activities for tea plantation began in 1879.

The last article of Chapter Three is written by Marie-Hélène Sauner who studies the present day Turkish kitchen and especially Anatolia’s colourful regional kitchens, from an anthropological perspective. The author talks about the formation of the Turkish kitchen and its multi-layered historical past and the importance of the rich topography. Her article examines today’s Istanbul kitchen and mostly authentic Anatolian cuisine under headings such as basic food items, kitchen location, cooking utensils, dishes, means of consumption, feast meals and the social function of the meal. The author draws attention to the population growth, migration between rural and urban areas, fast developing industry, communication, tourism and globalism. We learn from her article that the authentic form of the local kitchen remains the same as its original core.

Chapter Four in the book is reserved for kitchen utensils and tableware used in the palaces and has two richly illustrated articles. One article, written by Arif Bilgin, looks at kitchen utensils and tableware used by the Ottomans in the classical period in Topkapi Palace. The author has compiled a very comprehensive list of goods by scanning kitchen ledgers and inventories of utensils brought to the palace and records of repaired utensils or tin-coated utensils. Mostly made with copper, clay and wood, these items reflect the classical period culture. As in other areas, the transition of kitchenware and table utensils in the Ottoman Palace culinary culture began towards the end of the 18th century and gathered speed in the 19th century. In the second article of the chapter, Özge Samanci looks at utensils during this transition period once again by means of kitchen records and ledgers. This is a period when the Ottomans began to sit at high tables on chairs. This period is especially different with items symbolizing European lifestyle such as forks, knives, casseroles and European porcelain were introduced to and began to be used in the Ottoman Palace. The research articles by Bilgin and Samanci have distinct significance as they have taken advantage of ledgers and kitchen records as their source of information on the utensils and tableware used in the classical and transformation periods in the Ottoman palaces.

The last chapter of the book consists of two parts; a detailed bibliography of the old cookery books of Ottoman cuisine, and today’s adaptation of recipes based on these sources. In the first part, before explaining about the cookery books printed in old Turkish script, Turgut Kut presents very valuable information to scholars and enthusiasts alike by referring to manuscripts on cooking. In his bibliography, the author identifies 40 books, from the Turkish cookbook Malja’ Al-Tabbahin (printed in 1844 with Arabic script) to other cookbooks printed in 1927. Furthermore, in his article he includes a Turkish cookbook list that was printed between 1871 and 1926 in the Armenian script. This list alone provides extremely valuable information for researchers of culinary history.

It is both an enjoyable and painstaking task to bring out the hidden dishes of the old cookbooks. Adaptations of these dishes vary from chef to chef and from mouth to mouth. In the work that has dealt with Turkish and Ottoman cuisine from a historical perspective. The book concludes with a reminder of some dishes from the past. This book is a successful study on the Turkish cuisine as is written so far.

Table of Contents

Foreword – 5

Introduction and Acknowledgements – 9

Chapter 1: From Central Asia to Anatolia

A. Cuisine of Nomadic People: Scarcity and Simplicity

Mehmet Alpargu • Turkish Cuisine Inner Asia up until the 12th Century -17

B. Changes with Migration to the West: When Turkish, Arabic, Persian and Byzantine Culinary Cultures Meet

Altan Çetin • Turkish Cuisine in the Karakhanid, Seljuk and Memluk Periods – 27

Haşim Şahin • Cuisine during the Turkish Seljuk and Principalities Eras – 39

Nicolas Trépanier • Culinary Culture in Fourteenth Century Anatolia – 57

Chapter 2: Ottoman Cuisine in the Classical Period (15th-17th Centuries)

A. Food of the Palace, Festivals & Soup Kitchens

Arif Bilgin • Ottoman Palace Cuisine of the Classical Period – 71

Günay Kut • Banquet Dinners at Festivities – 93

Suraiya Faroqhi • Food for Feasts: Cooking Recipes in 16th and 17th Century Anatolian Hostelries (Imaret) – 115

Ömür Tufan • Helvahane and Halva Culture in the Ottomans – 125

B. The Relationship Between Health & Diet; Honey

Nil Sari • Food as Medicine – 137

Nuran Yildirim • Soups, Main Dishes and Desserts Recommended to Sick People – 153

(As Represented in 14th and 15th Century Turkish Medicinal Manuscripts )

Ümit Ekin • Honey: Production and Consumption of an Ancient Taste in the Ottoman Empire – 179

C. The Symbolic Relation Between Food & Power

Artun Ünsal • The Symbolism of Food: Tokens of Political Power and Status, – 179

Legitimization and Obedience and Challenging Authority

Chapter 3: Continuity & Change: From 19th Century to Present Time

A. Ottoman Elite Cuisine

Özge Samanci • The Culinary Culture of the Ottoman Palace & Istanbul During the Last Period of the Empire – 199

B. An Example from the Cuisines of the Communities

Marianna Yerasimos • Rum Cuisine in the Ottoman Period – 219

C. Symbols of Change: Olive Oil & Tea

Faruk Doǧan • The Production & Consumption of Olive Oil During the Ottoman Empire – 231

Kemalettin Kuzucu • Tea as a New Flavour in the Ottoman Culinary Culture – 243

D. The Present Day Turkish Kitchen

Marie Hélène-Sauner • “The way to the heart is through the stomach” Culinary Practices in Contemporay Turkey – 261

Chapter 4: Kitchen Utensils & Tableware Used in the Ottoman Palaces

Arif Bilgin • Kitchen & Dining Table Utensils Used in the Ottoman Palace During the Classical Period (15th-18th Centuries) – 283

Özge Samanci • From Alaturka to Alafranga: Kitchenware and Tableware in the Ottoman Palace in the 19th Century – 307

Chapter 5: Tastes from the Past

A. Turkish Cookbooks from Ottoman to Turkish Republican Era

Turgut Kut • A Bibliography of Turkish Cookery Books up to 1927 – 329

B. Ottoman Recipes

Soup

Tarhana Soup – 339

Kebabs, Stews, Griddled, Meat Balls

Muhzir Kebab – 341

Mazruf Kebab – 343

Griddled Swordfish with Pureed Hazelnut Sauce – 345

Trotter Stew – 347

Köfte – 349

Stuffed Vegetables- Dolma & Sarma

Dressed Dolma – 351

Stuffed Grapevine, Chard, Mulberry, Hazelnut & Green Salad with Meat – 353

Börek & Manti

Kapak Böreǧi – Cover Pie – 355

Manti – 357

Lamb Stews with Vegetables and Fruits Çeşidiyye – 359

Summer Vegetables Braised with Lamb – 361

Pilafs

Black Pilaf – 363

Aubergine Pilaf – 365

Keşkek or Herise

Herise – 367

Pilaki or Vegetables in Olive Oil

Mackerel in Olive Oil – 369

Rice Stuffed Vine Leaves with Sour Cherries – 371

Pickle & Salads

Grape Pickle – 373

Leaf Lettuce – 375

Desserts

Baklava – 377

Strained Palace Aşure – 379

Helva-yi Hâkanî – 381

Tavukgöǧsü – Chicken Breast Pudding – 383

Creamy Kadayif – 385

Turkish Delight – 387

Fruit Compotes & Sherbets

Apricot & Plum Compote – 389

Rose Sherbet – 391

Further reading

*Dr. Arif Bilgin, Lecturer at History Department, Sakarya University, Turkey.

**Ozge Samanci. Yeditepe University, Fine Arts Faculty, Istanbul, Turkey.

Muslim Heritage:

Send us your e-mail address to be informed about our work.

This Website MuslimHeritage.com is owned by FSTC Ltd and managed by the Foundation for Science, Technology and Civilisation, UK (FSTCUK), a British charity number 1158509.

© Copyright FSTC Ltd 2002-2020. All Rights Reserved.