Today, chess continues to captivate minds across the globe, transcending borders and generations. The International Day of Chess, celebrated on July 20ths, reminds us of this timeless game's enduring appeal. In a recent headline-making moment, Norwegian grandmaster Magnus Carlsen, currently ranked world No. 1, was defeated by 19-year-old Indian prodigy Gukesh Dommaraju, the reigning world champion. After Dommaraju's final move, Carlsen, 34, stood up in frustration, slamming his fist on the table before shaking hands with his young opponent; an emotional moment that echoed the intensity and drama that chess has evoked for centuries, from the courts of the Abbasid caliphs to today’s digital arenas.

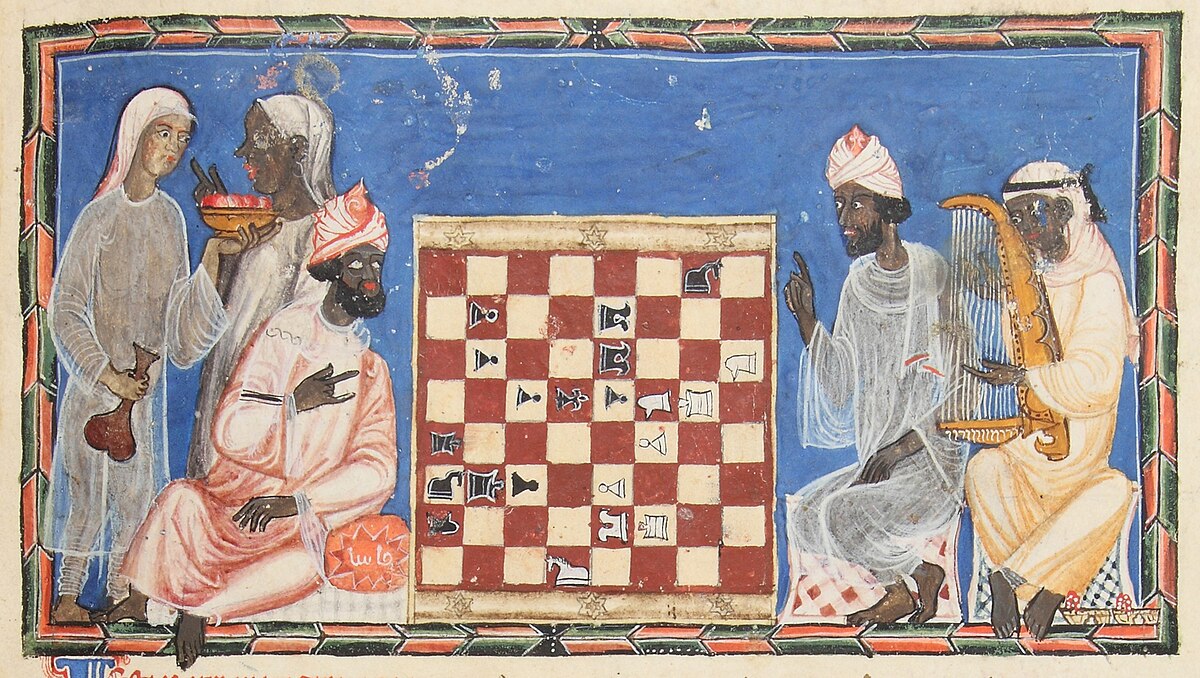

Figure 1. 1283 A.D. Miniature from Alfonso X’s Book of Chess, Dice and Board Games. African Muslims playing chess. The book also has illustrations of white and Arab Muslims playing chess in al-Andalus. Europeans loosely called the Muslims ‘Moors’, blending the usage of the name for people of both Arab and Berber ancestry (Wikipedia)

***

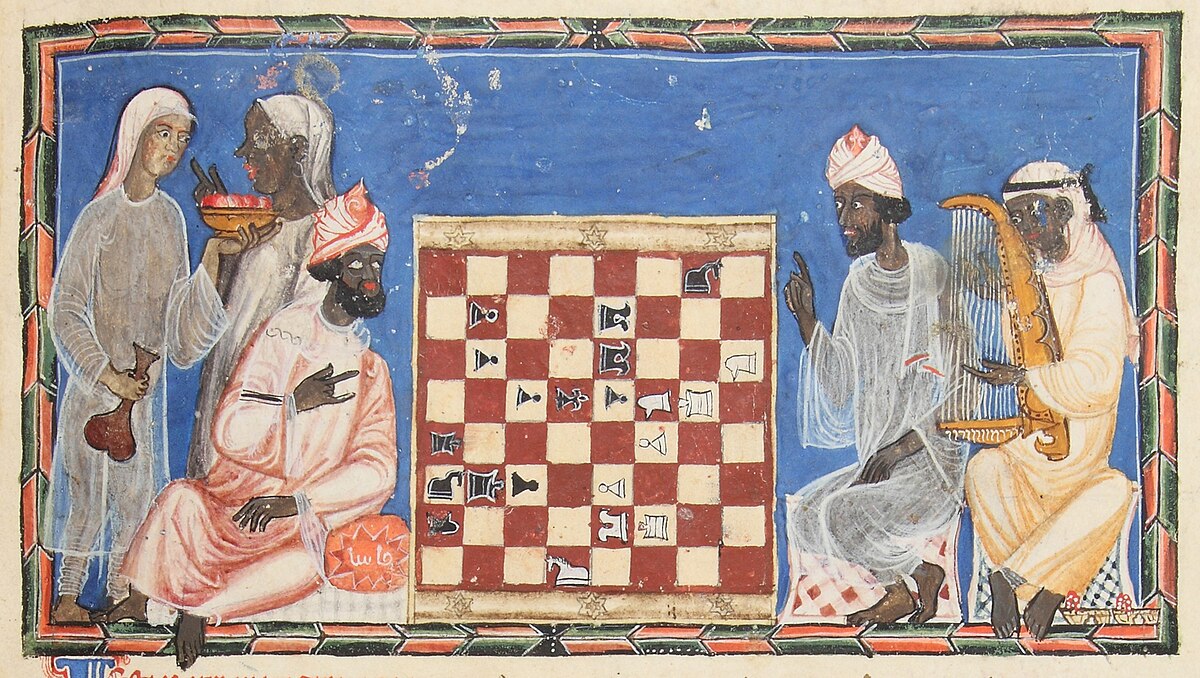

Figure 2. From the 14th century Islamic Persian manuscript “A Treatise on Chess”. The Ambassadors from India present the Chatrang to Khosrow I Anushirvan, “the Immortal Soul”, King of the Sasanian Empire (Wikipedia)

Chess is a game of mental combat played by most nationalities on 64 squares with 32 pieces. Despite its size and unassuming appearance, the number of possible games that can be played is beyond counting. The stories,figures, and individuals surrounding chess give it a mysterious dimension, and although its definite origins remain unknown, it is said to have come from either India or Persia.

Ibn Khaldun connects chess to an Indian named Sassa ibn Dahir, an eminent man of wisdom. There was an ancient Indian game called Chaturanga, which means “having four limbs,” probably referring to the four branches of the Indian army of elephants, horsemen, chariots, and infantry. Chaturanga was not exactly chess, but a precursor to today’s chess. A 14th-century Persian manuscript describes how an Indian ambassador brought chess to the Persian court, from where it was taken to Europe by Arabs going to medieval Spain. Before it reached Europe, the Persians modified the game into Chatrang, using it in their war games.

“Shatranj (chess) is a training for the mind, like wrestling is for the body.

It teaches foresight, planning, and subtlety.

The wise do not merely play to win but to sharpen the intellect.”

(Attributed to Ibn Khaldun notes in his Muqaddimah)

Shatranj as it was then called, in Persia and absorbed it into their culture. At that time, the playing pieces were Shah, the king; Firzan, a general, who became the queen in modern times; Fil was an elephant that became the bishop; Faras was the horse; Rukh was a chariot that is now the castle or rook; and Baidaq was the foot soldier or pawn. The word “checkmate” is Persian in origin and a corruption of Shahmat, meaning “the king is defeated”.

Figure 3. Abu Bakr ibn Yahya al-Suli’s statue in Turkmenistan. He was a Muslim Turkic scholar and a court companion of three Abbasid caliphs… (photo by releasethedogs at Flickr)

The game was very popular with the general public as well as the nobility, and the Abbasid caliphs particularly loved it. The great masters, though, were Al-Suli, Al-Razi, and Ibn al-Nadim. In the mid-20th century, Russian grand master Yuri Averbak played an astonishing move in one of his championship games, which he won. Many thought this to be an ingenious new idea, but it was actually devised more than a thousand years ago by Al-Suli. Arab grand masters wrote copiously about chess, its laws, and its strategies, and these spread all over the Muslim world.

There were books on chess history, openings, endings, and problems. The Book of the Examples of Warfare in the Game of Chess, written around 1370, introduced the chess game “The Blind Abbess and Her Nuns” for the first time. Chess reached Andalusia, Muslim Spain, in the early ninth century, and from there, the game spread among Christian Spaniards and the Mozarabs, and reached northern Spain as far as the Pyrenees, crossing the mountains into southern France. The first European records to mention chess go back to 1058, when Countess Ermessind of Barcelona donated her crystal chess pieces to St. Giles monastery at Nimes in her will. A couple of years later, Cardinal Damiani of Ostia wrote to Pope Gregory VII, urging him to ban the “game of the infidels” from spreading among the clergy.

Chess was also carried via the trade routes from Central Asia to the southern steppes of early Russia. Seventh-and eighth-century Persian chess pieces have been found in Samarkand and Farghana. By 1000, chess had spread even farther on the Viking trade routes as the Vikings carried it back to Scandinavia. Those trade routes meant that by the 11th century, chess had made its way as far as Iceland, and an Icelandic saga written in 1155 talks of the Danish king, Knut the Great, playing the game in 1027. By the 14th century, chess was widely known in Europe, and King Alfonso X, known as “the Wise,” had produced the Book of Chess and Other Games in the 13th century. For the last eight centuries, chess has gone from strength to strength, producing a few funny stories along the way, such as the Robotic Chess Master of 1769. Hungarian Wolfgang de Kempelen decided to give a gift to his queen, Empress Maria Theresa, who was a chess fanatic. He gave her a robot machine called the “Iron Muslim”, later renamed “Ottoman Turk”, which played chess skilfully, beating high-ranked players of the day. Inside, all cramped up, was a chess master. Peple travelled miles to marvel at the turban-wearing robot. In fact, 15 separate chess players inhabited it for 85 years, in Baghdad.

Figure 4. The Mechanical Turk, also known as the Automaton Chess Player (German: Schachtürke, lit. ’chess Turk’; Hungarian: A Török), or simply The Turk, was a fraudulent chess-playing machine constructed in 1770, which appeared to be able to play a strong game of chess against a human opponent. (Wikipedia)

5 / 5. Votes 1

No votes so far! Be the first to rate this post.

Muslim Heritage:

Send us your e-mail address to be informed about our work.

This Website MuslimHeritage.com is owned by FSTC Ltd and managed by the Foundation for Science, Technology and Civilisation, UK (FSTCUK), a British charity number 1158509.

© Copyright FSTC Ltd 2002-2020. All Rights Reserved.