The scholars of Islamic culture worked extensively in the combined fields of botany, herbals and healing. Several scholars contributed to the knowledge of plants, their diseases and the methods of growth. They classified plants into those that grow from cuttings, those that grow from seed and those that grow spontaneously. Great Muslim figures such as Al-Dinawari, Ibn Juljul and Ibn al-Baytar made great progress in the field, as this article demonstrates. Muslim botanists knew how to produce new fruits by grafting; they combined the rose bush and the almond tree to generate rare and lovely flowers. The royal botanical gardens contained an endless variety of plants, indigenous and exotic, cultivated for their brilliant foliage, their delightful fragrance, or their culinary and medicinal virtues. In particular, they dealt with plants in a variety of ways, which included their study from a philological perspective, but most importantly for their curative and healing properties.

FSTC Research Team*

Table of contents

1. Plants in Islamic scholarship

2. Herbs and Healing in Islamic Scholarly Tradition

3. Al-Dinawri the founder of Arabic botany

4. Botanical contributions from the Western Islamic tradition

4.1. Ibn Juljul

4.2. Ibn Samjun

4.3. Ibn Al-Wafid

4.4. Al-Ghafiqi

4.5. Al-Idrisi

4.6. Al-Qalanisi

4.7. Ibn Sirabiyun and Ibn al-Suri

6. Medicinal Plants and their Actions

6.1. Syrups

6.2. lohochs

6.3. Decoctions

***

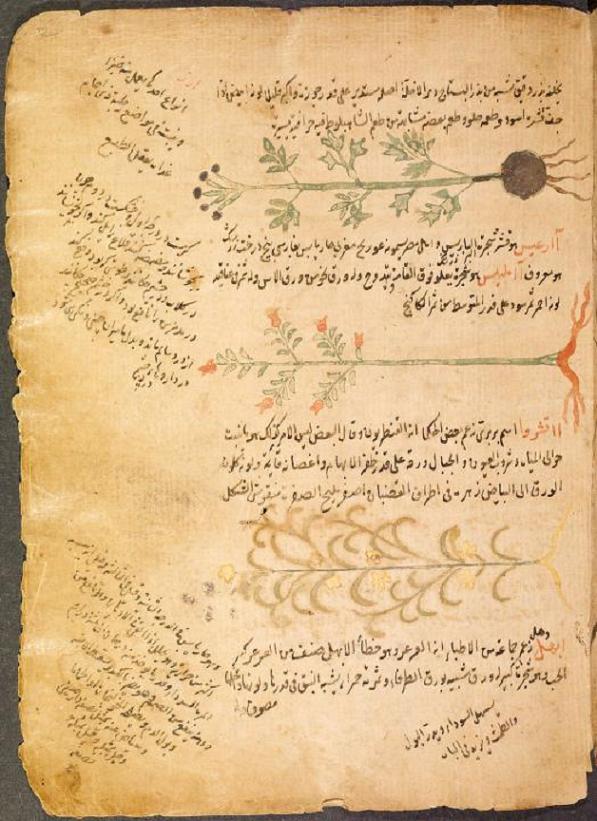

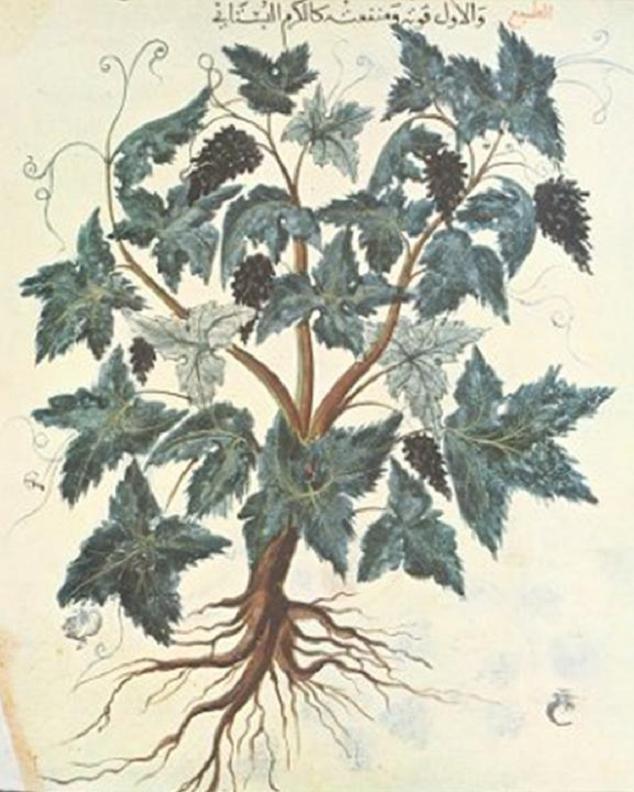

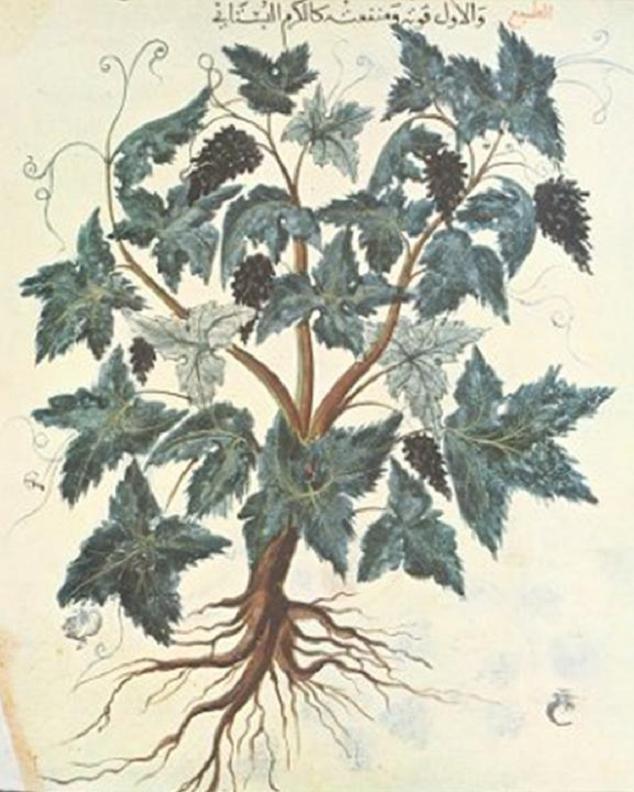

The Qur’an provided the initial impetus for the investigation of herbs by Islamic writers, for plants are named in the depiction of Paradise and are used as signs of the Creator’s power and majesty [1].

Inspired by their faith, Muslims worked extensively in this area. Several scholars contributed to the knowledge of plants, their diseases and the methods of growth. They classified plants into those that grow from cuttings, those that grow from seed and those that grow spontaneously [2].

|

|

|

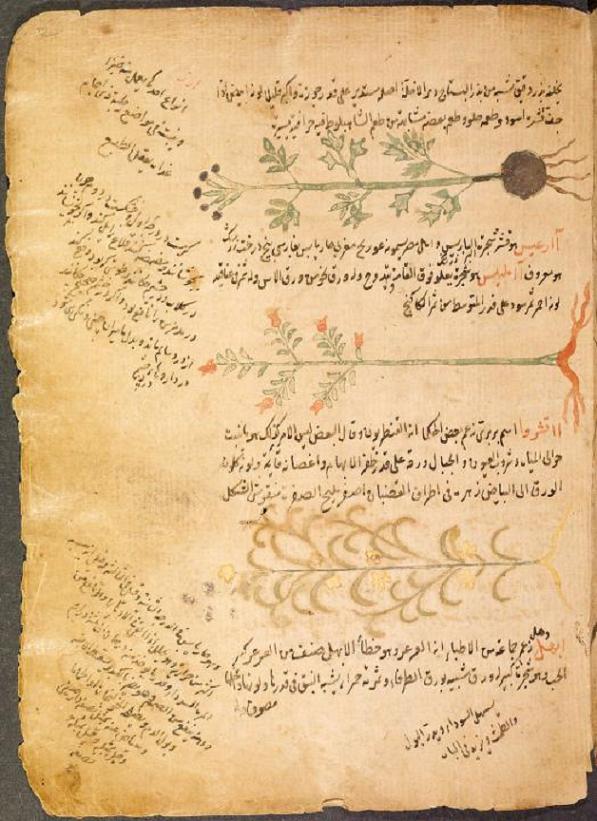

Figure 1a-b: Composite images illustrating the diversity of plants. (Source a – Source b). |

|

Muslim botanists knew how to produce new fruits by grafting; they combined the rose bush and the almond tree to generate rare and lovely flowers [3]. The royal botanical gardens contained an endless variety of plants, indigenous and exotic, cultivated for their brilliant foliage, their delightful fragrance, or their culinary and medicinal virtues [4].

In particular, they dealt with plants in a variety of ways, which included their study from a philological perspective, but most importantly for their curative and healing properties. This latter function of plants is the focus of the second half of this article, following a review of the Muslim approach to plants from other perspectives.

1. Plants in Islamic scholarship

Considerable information about herbs is contained in medieval Islamic literature, where plant life is closely associated with philology, medicine and agronomy. In addition, plants were discussed in philosophical, magical, encyclopaedic and geographic works [5].

Since al- Al-Asma’i (740-828 C.E.), author of the famous Kitab al-nabat wa-‘l-shajar, to eliminate doubt concerning the correct meaning of a botanical term, the philologists described the plant, including the names of its different parts as well as the synonyms which refer to it. Among these synonyms are the names which the plant carries during its different stages of growth [6]. As for systematics, all kinds of different systems may be encountered, ranging from the simple alphabetical order to divisions according to practical use; divisions into trees, flowers, and garden vegetables; into trees (including shrubs) and plants, with a further subdivision of the latter group; trees may also be subdivided according to the edible qualities of the skins and kernels of their fruit [7].

Many of the Muslim early philological works are lost, such as that of Al-Shaybani (d. ca. 204/820), Ibn Al-Arabi (d. 231/844), Al-Bahili (d. 231/845) and Ibn as-Sikkit (d. 243/857), but their works, however, are extensively quoted in later books by Abu Hanifa Al-Dinawari, Ibn Sidah [8] and others.

As a result of the wide geographical spread of Islam and extensive travel within its territories, adding information from Middle Eastern, Indian, and North African sources, there emerged a rich botanical literature in which Muslim authors sought to determine the true significance of the plants and to establish their synonyms. Progressively, the enlarged plant terminology supplemented and often replaced the older Arabic nomenclature [9].

|

|

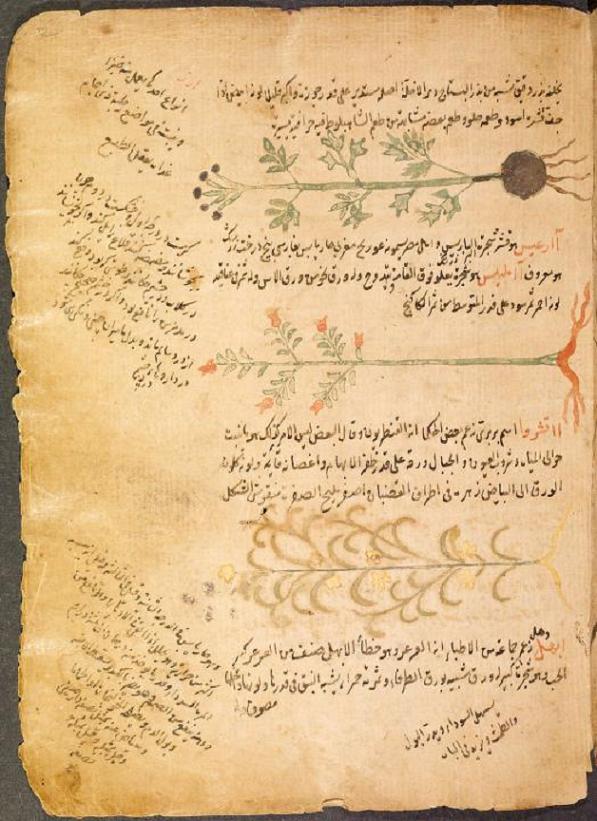

Figure 2: Two sample pages from Ibn al-Baytar’s treatise Jâmi mufradat al-adwiya wa-‘l-aghdiya. Suleymaniye Library, Ayasofya, MS 3748. Read: Nil Sari, Food as Medicine in Muslim Civilization. |

Ibn Hajjaj, in his Sufficient, covered the subject of botany, combining it with grammatical considerations [10]. In several literary works of belles lettres, Al-Djahiz and Ibn Qutayba described curious aspects of plants. In the scientific field, the chemical corpus of Jabir ibn Hayyan discussed herbs used in the composition of elixirs [11]. Abu Ubaid al-Bakri wrote a treatise on the plants and trees of Andalusia [12], whilst the anonymous ‘Umdat al-tabib fi ma’rifat al-nabat li-kull labib was a pioneering attempt at the classification of plants by genus (jins), species (naw’) and variety (sanf), which surpassed all previous classifications [13]. The well know Andalusian philosopher Ibn Bajja (Avempace, d. 1138,) was also interested in botany. In Kitab al-nabat (liber de Plantis), he dealt with the physiology of plants and emphasised their infinite variety. He divided plants into the perfect and imperfect (those lacking the main organs), and also wrote on their reproduction cycles [14].

Muslim scholars were fully conscious of the fact that the plants distribution is profoundly modified by the changes of topography and difference in the character of the soil. Accordingly, they distinguished a number of plant types according to whether the plant is found in deserts and wilderness, on mountain tops, on the river bank, on the sea-shore, in lakes, in hollows, in sandy soil, in alkaline soil or in good soil [15]. Thus it is clear that the majority of the plants grow on the surface of the earth but a few of them grow in water, like cane, rice, narcissus and some species of reeds. Among the plants are those which grow on the surface water such as sea weed and green moss [16]. Another type of plant is that which grows on trees such as creepers, and another still is that which grows on hard rocks, such as Khadra’ al-dimam (a thorny bush) [17].

Ibn Juljul of Cordova is appreciated for his personal, local knowledge, and ability to locate the geographic origin of plants. On Sasaliyus (Seseli), he says: `I have frequently seen it in Galicia.’ On Fu (Valeriana), he declares that he has seen it often, and it grows plentifully in the mountains around Toledo [18]. On Qurrat al-‘ayn (Nasturtium or Sium), he states ‘this small bush is plentiful in our area’ (‘indana) [19]. He saw it mostly at the foot of the mountains of Cordova, and has often collected it there and stored it for use. In the article on Thaisiya (Thapsia), Ibn Samjun reports on the authority of Ibn Juljul and Ibn al-Haytham, “among our learned men” (min ‘ulamd’ina) that it comes from the Maghrib, from Fez and other places; Ibn Juljul says that it is imported from there to Cordova [20].

Kruk points out that a very interesting part of mediaeval Islamic botany is found in the work of scholars who discuss botanical problems of a more general nature. Such discussions may also be found in a theological context, where they serve as proof of God’s wisdom. For instance, Al-Ghazali (d. 505/1111) [21] describes creation, from the heavens down to the plants [22]. Another example is Ibn al-Nafis’ minute description of how the different parts of plants develop from the seed [23]. Most important, however, in this respect are the natural philosophers, who discuss subjects such as the place of plants on the scale of living beings; the concept of species, and the measure in which species were fixed or variable; reproduction, including spontaneous and artificial generation, the latter belonging to the field of magic and alchemy; the measure of sensibility of plants; and the functions of their different parts [24]. Extensive references to plants and flowers are not only found in Bedouin poetry, but also in later poetry, especially in the genres of rawdiyat, rabi’iyat and zahriyat, that is poems concerning gardens, springs and flowers [25].

|

|

|

|

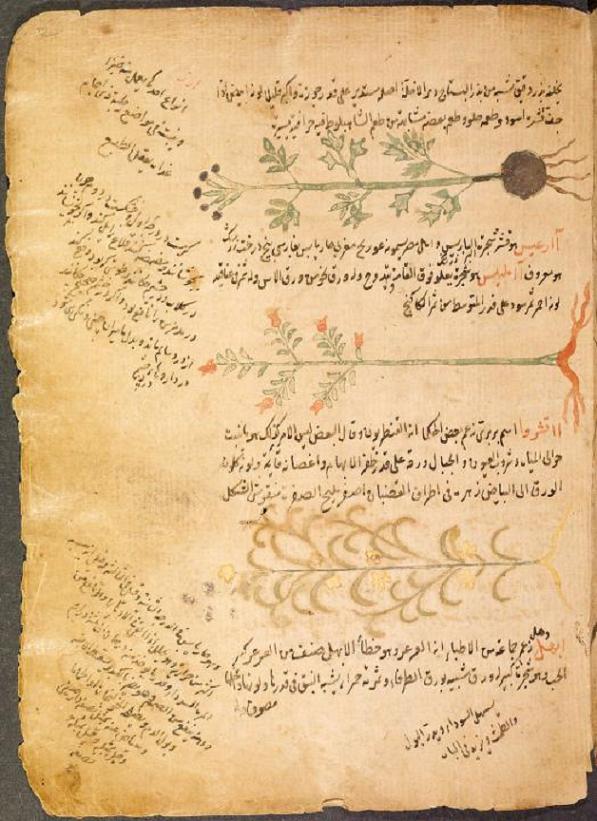

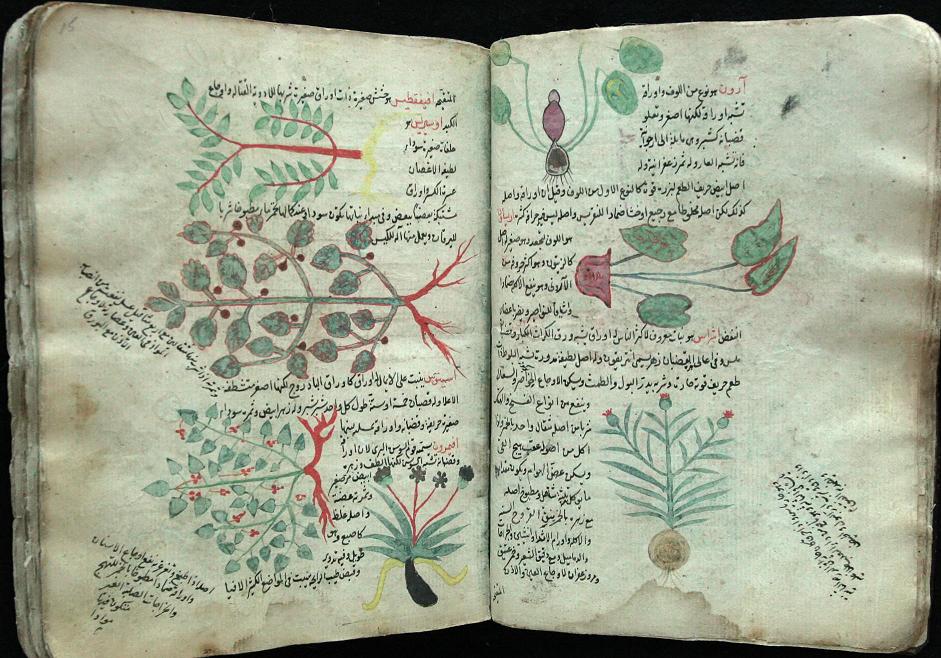

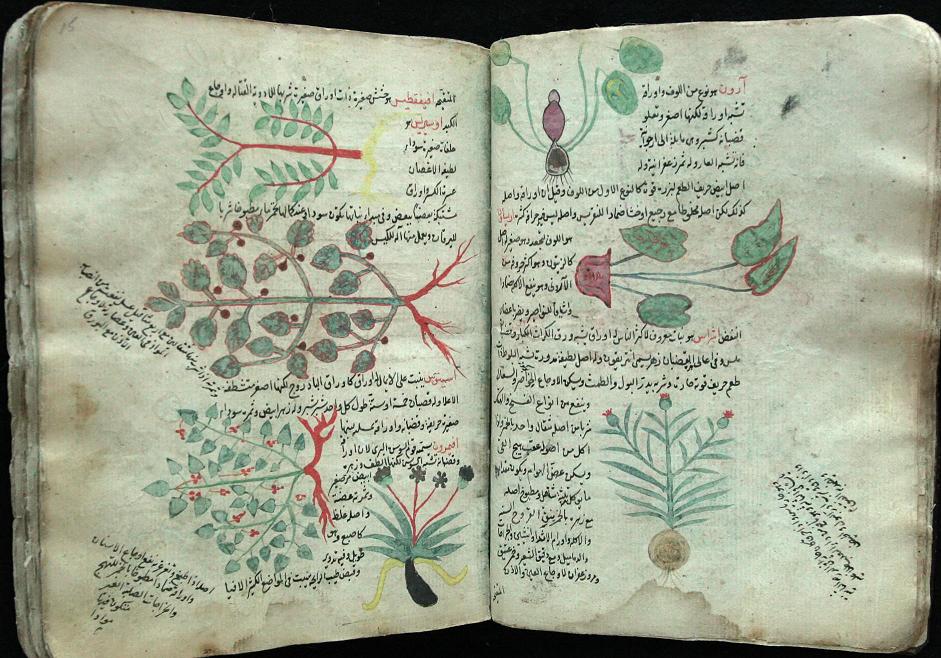

|

Figure 3a-d: Arabic botanical manuscript from the 15th century arranged in alphabetical order with illustrations of plants in vivid colours at Princeton University Library, MS 583H. © Princeton University Library, Department of Rare Books and Special Collections. See the electronic edition of the manuscript. |

|||

Muslim travellers, for their part, provided a very rich account on the nature, variety, location, and above all the origin of various plants. Their writings compose a precious literary heritage. Together with the relevant writings of other experts in various fields, these text constitute the first extensive and systematic botanical survey of vast and diverse lands. The Cordova physician Al-Ghafiqi was born in Ghafiq, a town near Cordova in 1165. In his travels through Spain and North Africa, he collected plants, giving their names in Arabic, Latin and Berber, precisely and accurately [26]. Abu Zakariya, another botanist and agriculturist, worked in Seville in the latter part of the 12th century. His treatise on agriculture, known as Al-Filaha, was the outstanding medieval work on the subject [27]. He consulted Greek and Arabic authorities, and got much of his material from the study of husbandry in Spain itself. He discussed five hundred and eighty-five plants and described the cultivation of some fifty fruit trees. He made new observations on grafting and discussed the properties of soil and methods of fertilizing it [28].

The Moroccan traveller Ibn Battuta (d. 1377) described in his Rihla the fruit of Isfahan (apricots, quince, grapes, watermelons, coconut) and the fruit trees of India (the mango tree and sweet orange). In Malabar, he draws attention to cinnamon and the Brazil nut; in the Maldives, he observes the coconut tree, the palm tree, the lemon tree and others, whilst in Java, his attention is caught by benzoin, camphor and clove amongst others [29].

|

|

Figure 4: Front cover of Ibn al-Baytar (d. 646 H / 1248 AD): Tafsir kitab Diyasquridus fi al-adwiya al-mufrada (A Commentary on Dioscorides’ Materia Medica), edited by Ibrahim Ben Mrad (Carthage (Tunisia): Bayt al-hikma, 1990). |

Botanical data may be found in encyclopaedias, such as those of Al-Qazwini and Al-Nuwayri, and geographies, such as those of Al-Biruni and Al-Idrîsî [30]. A lost treatise of Al-Idrîsî on Materia Medica has been discovered in Constantinople. It contains a description of 360 simples (medicines, generally vegetable, containing only one ingredient), and is very important, if not from the medical, at least from the botanical point of view [31]. There is also the impressive account of Egyptian flora by ‘Abd al-Latif al-Baghdadi, who visited Egypt in 1203 [32].

2. Herbs and Healing in Islamic Scholarly Tradition

One of the major uses of plants and herbs was for healing purposes. In Egypt, more than anywhere else, the population has retained the tradition of seeking healing by means of simples, the knowledge of whose healing powers have been transmitted from generation to generation [33]. Everyone understands their health problems and what is needed to cure them, be they simples from the animal vegetable or mineral worlds [34]. A cure is sought from a druggist; a physician is only consulted when matters reach levels of high gravity [35]. Throughout the Muslim world, the method of obtaining drugs for the treatment of the sick varied considerably at different times and places [36]. In some instances the patient was told what drugs to get with instructions as to how the medicine should be taken; in others he was given a prescription that had to be filled out by the pharmacist; in many instances the physician compounded the prescription from his own supply of drugs and sold it to the patient. Too often the pharmacist recommended a remedy after hearing the patient’s complaint, without examining him. However, in the latter part of the Abbasid period, the well-to-do patient was given a prescription that had to be filled out by the pharmacist. When treating a nobleman or a person of high rank, the physician was supposed to take a draught of the medicine in his presence as a guarantee that it was a safe remedy [37].

During the latter part of the Abbasid period and the Western Caliphate, Muslims made real contributions to the knowledge of organic and inorganic medicinal remedies, as well as their compounding of these remedies [38]. The separation of the medical from the pharmaceutical professions was started by the Abbasids, largely due to the advances that had been made in Materia Medica and the knowledge of compounding drugs. The large hospitals in Iraq had a pharmacist on their staff, and a well-equipped pharmacy, where drugs were compounded and the physicians’ prescriptions were filled [39]. In these pharmacies drugs and spices were stored [40]. Amongst the Baghdadi scholars was Masawaih al-Maradini, a Jacobite Christian doctor from Mardin in Upper Mesopotamia, who lived first in Baghdad and then under the reign of Caliph Hakim in Cairo [41]. He became famous, at least in the Latin West, for his pharmacopoeia, which was divided into several sections, dealing with correctives to medicines, simple purgative remedies, composite medicines and lastly medicines intended for specific individual diseases [42].

|

|

Figure 5: Rare manuscript copy of book of simple drugs attributed to Ibn al-Baytar, held in The Royal Library, Copenhagen Cod. Arab. 114 folio 2b. In fact the manuscript is a copy of Kitâb Taqwîm al-Adwiyah fî mâ-shtahara min-al- a’shâb wa-l-aqâqîr wa-l-aghdhiyah (Book for determining medicaments of those herbs, medical plants and nourishments which are publicly known) by Ibrâhîm ibn Abî Sa’îd al-Maghribî al-‘Alâ’î, who wrote it in the middle of the 12th century. (Source). |

The dominant feature, however, is that nearly all drugs were derived from plants, with a much smaller proportion of animal and mineral origin [43]. Abul-Abbas, of Seville, was the first to apply the principles of botanical science —previously principally devoted to agriculture— to the purposes of the apothecary and the physician [44]. Regulation of diet was an important recommendation, together with respecting the first principle of medicine, that is the preservation of health preceded the medicinal use of plants, and respect of the second principle, the restoration of health when it was lost or weakened [45]. However, there was no very clear dividing line between food and medicine, and many plant products might well fall into both categories [46].

Al-Dinawari (d. 895 A.D) might well be termed the ‘father of Muslim botany’. His work was, in good Arab tradition, a poetic anthology about plants, but this did not prevent it from containing serious scientific descriptions of exact terminological precision. Medieval doctors and pharmacists had to know it by heart in order to gain the authority to practice [47].

Earlier than Al-Dinawari, were Al-Kindî and Al-Tabari. Al-Tabari’s (d. 855) encyclopaedic work entitled Firdaws al-Hikma (The Paradise of Wisdom), although including many other sciences such as climatology, astronomy and philosophy, devotes an important section to botany. Al-Kindî (ca. 800-ca. 866), however, was an innovator in the production of a herbal manual with the main objective of teaching useful botanical pharmacology, as well as toxicology and medicines gained from minerals [48]. His Aqrabadhin (Medical formulary) includes 222 recipes employing at least 319 substances known to Muslim pharmacology in the 9th century [49].

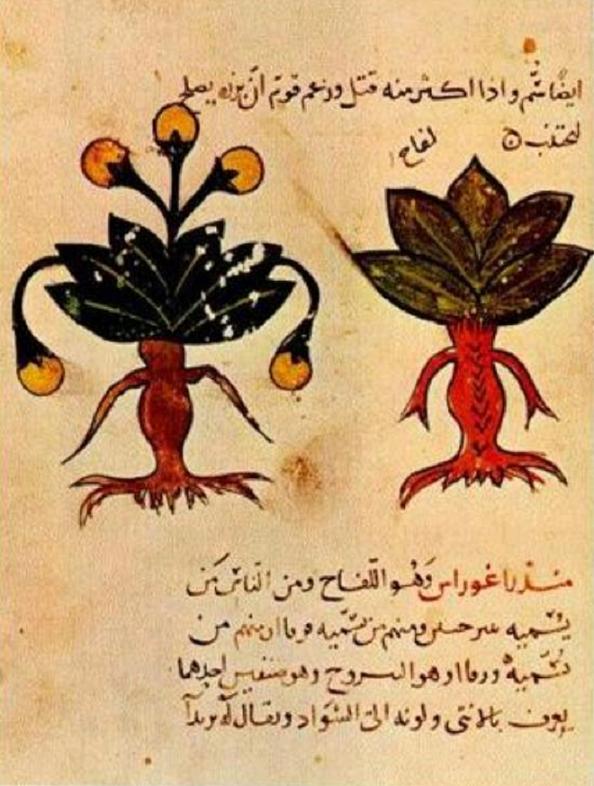

As is generally the case with early Islamic scientists (Jabir Ibn Hayyan, Hunayn Ibn Ishaq and others), the Greek influence is clearly visible for example with Ibn Wahshya (860-ca. 935). As in Byzantine pharmacy and medical botany, Scarborough notes, there is little separating the lore of the farm from medical herbalism, and there is little that divides toxicology from folklore in the Kitab al-sumum wa-‘l-tiryaqat (Book of poisons and antidotes) attributed to Ibn Wahshiya [50]. However, the same author was also responsible for Al-Filaha al-nabatiya (Nabatean Agriculture), the first comprehensive encyclopaedia on plants and agriculture [51], which is comprehensively summarised by Fahd [52]. Fahd provides a succinct and yet immensely informative summary of a complete classification of plants derived from the work [53].

|

|

Figure 6: Drawings from Arabic manuscripts of the cultivated and the uncultivated kinds of the hindiba, a plant well known to Muslim pharmacologists and herbalists for its therapeutic virtues which include cancer treatment. From left to right: (a) Hindiba in an Arabic version of Dioscorides’ Materia Medica translated by Abdullah al-Huseyin b. Ibrahim al-Natili (Kitabu ‘l-khasa’is, Topkapi Museum Library, Ahmed III, MS 2127; (b) Hindiba illustrated in Kitab min al-tibb fi ‘l-ahkami ‘l-kulliyyat wa’l-adwiya ‘l-mufrada, Suleymaniye Library, Ayasofya, MS 3748. See: Nil Sari, Hindiba: A Drug for Cancer Treatment in Muslim Heritage. |

Islamic botany gradually adopted an advanced methodology and approach, which brought the science close to our modern parameters. This is obvious, for instance, in the Kamil al-Sina’a of Ali b. Abbas al-Madjusi (d. 994). In this treatise, the pharmaceutical properties of the simple drugs are described in fifty-seven chapters. Among the latter are included those on botanical simples, animal simples, mineral simples, medicinal oils, taste and odours of simples, odour, strength, constipating and opening qualities, deterioration, pain, decreasing ability, cicatrisation effects, diuretic effectiveness, sudorific qualities, strength of seeds, leaves, and roots, extracts, gums and humours of drugs; also stones, salts, galls, dungs, diarrheic simples, and dosages are explained in separate chapters [54]. The descriptions are not given in alphabetical order nor are they always on simples. Frequently, prescriptions for a compound remedy are given so that the treatise does not effect a rigid separation between simples and compounded drugs [55]. The compounded drugs are also described in a separate section but the entire book is full of interesting prescriptions, giving a very complete account of the medicine of the day in a well organised fashion [56].

The Muslims progressed well beyond their Greek predecessors in the use of plants for medicinal purposes and the Muslim list of drugs contained several hundreds of remedies unknown to the Greeks [57]. Ibn Juljul, for instance, was conscious of the fact that medicine and botany had developed since the days of Dioscorides, and new items used for medication had come from the East, or were found in Al-Andalus [58]. Muslims gave Arabic names to plants and medicines they came across for the first time, many such names are still used today [59]. In the work of Ibn al-Awwam six hundred plants possessing medicinal properties are enumerated; in that of Ibn Al-Baytar more than three hundred, hitherto unclassified or unknown, are mentioned and described [60].

3. Al-Dinawri the founder of Arabic botany

Ābu Hanīfah Āhmad ibn Dawūd Dīnawarī (828 – 896) was a polymath excelling as much in astronomy, agriculture, botany and metallurgy and as he did in geography, mathematics and history. He was born in Dinawar (in modern day Western Iran, halfway between Hamadan and Kermanshah). He studied astronomy, mathematics and mechanics in Isfahan and philology and poetry in Kufa and Basra. He died on July 24, 896 at Dinawar. His most renowned contribution is Book of Plants, for which he is considered the founder of Arabic botany.

|

|

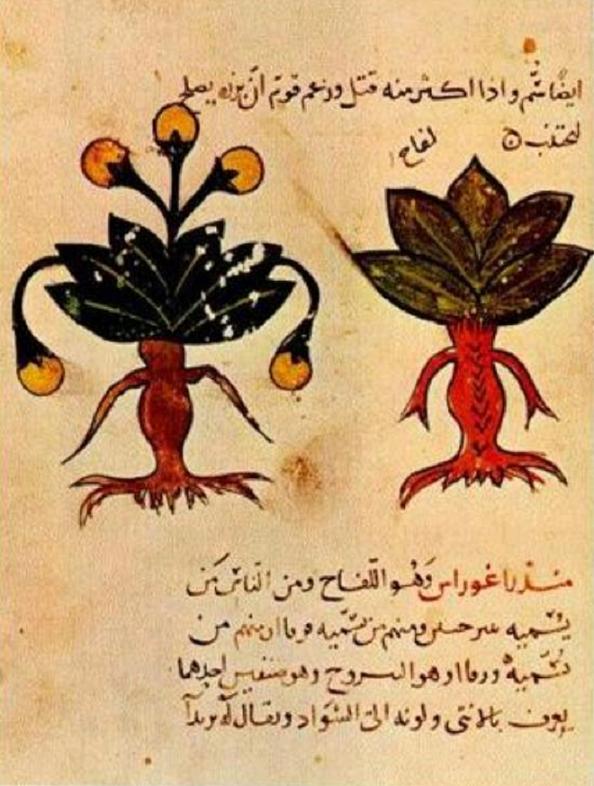

Figure 7: Mandrake plant from an Arabic medical manuscript in Istanbul mosque. Source: Mohamad S. Takrouri, Surgical, medical and anesthesia in the Middle East: Notes on Ancient and medieval practice with reference to Islamic-Arabic medicine. |

Al-Dinawari is certainly one of the earliest Muslim botanists. His work, largely confined to the flora of Arabia [61], is perhaps the most comprehensive and methodical philological work on herbs. His treatise Kitab al-Nabat is characterised as “the most comprehensive and methodically most superior work of this philologically-orientated botany [62].” Al-Dinawari’s work was long considered lost, but thanks to the particular attention of the German scholar Silberberg, it was made known in a thesis from Breslau in 1908 [63]. The thesis contains the descriptions of about 400 plants from the book of al-Dinawari [64]. However, what is described by Silberberg is just a part of what has survived, and there have been editions of different parts of the work by different authors. In particular, Lewin has collated parts of the alphabetical section from the Istanbul manuscript [65]; whilst the sixth volume has been reconstructed by Muhammad Hamidullah from citations collected from large dictionaries and monographs and contains the descriptions of 637 plants (from the letters sin to ya) [66].

Al-Dinawari’s information is based on older written sources, on oral information from Bedouins, and, occasionally, on personal observation [67]. His book Kitab al-nabat consists of two sections, one being an alphabetical inventory of plant names (and thus the first alphabetically-ordered specialised dictionary), the second section contains monographs on plants used for specific practical purposes: kindling; dyeing; bow-making. There also is a very interesting chapter on mushrooms and similar plants (to the latter belong the parasitic broomrapes Balanophoraceae) [68]. This chapter (included in Lewin’s edition) gives important information on the gathering, use, and growth of a number of mushrooms [69]. Al-Dinawari also devoted one chapter to the classification of plants (tajnis al-nabat) which he mentions in one of the volumes that have survived [70]. The contents and sources of al-Dinawari’s book are discussed by Bauer [71], who observes that Al-Dinawari had in mind a scope far beyond a mere botanical dictionary, intending to describe all the aspects of Bedouin life which had a botanical component [72]. In his exposition on the earth, Al-Dinawari describes a variety of soils, explaining which is good for planting, its properties and qualities, and also describes plant evolution from its birth to its death, including the phases of growth and production of flower and fruit [73]. He then covers various crops, including cereals, vineyards and date palms. Relying on his predecessors, he also explains trees, mountains, plains, deserts, aromatic plants, woods, plants used as dyes, honey, bees, etc [74].

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 8a-d: Discorides (ca. 40-90) was an ancient Greek physician, pharmacologist and botanist from Asia Minor. He is the author of the influential Materia Medica, of which several Arabic versions and commentaries were produced. (a): An illustration and description of a Cinnamomum tree in a 10th-century Arabic manuscript of the Materia Medica; © State University Library, Leiden (Source); (b-c) two illustrations from an Arabic manuscript of De Materia Medica from Baghdad dated 621 H/1224 (Source b) (Source c); (d) another Arabic manuscript of the work of Dioscorides from Baghdad dated 735H/1334 ©The British Library, MS Or. 3366 (Source). |

|||

4. Botanical contributions from the Western Islamic tradition

4.1. Ibn Juljul

One of the most famed Muslim herbalists, noted earlier, is Ibn Juljul. Abu Da’ud Sulayman b. Hassan, known as Ibn Juljul, was born in Cordova in 332 H/ 944 CE. He studied grammar and tradition from the age of ten; at fifteen he began the study of medicine in which he became very skilful. We are told that he was the personal physician to Al-Mu’ayyad Billah Hisham, Caliph from 977 to 1009 CE, during whose reign he wrote most of his medical works[75].

Ibn Juljul seems to have been concerned mainly with the herbal, pharmaceutical aspects, which formed a vital part of medical work at that time [76]. He shared much the same medical background and training as Al-Zahrawi; they both worked and wrote during the latter days of the Caliphate in Andalus [77]. Ibn Abi Usaybi’a and Al-Qifti, the two best-known historians of medicine, both speak highly of Ibn Juljul, though they give slightly different lists of his writings. Both agree that he wrote a history: Tabaqat al-Atibba’wa’l Hukama, which has been edited in recent years [78]. This history has brief sections on every period, starting with the legendary fathers of medicine, but is probably of greatest interest for Ibn Juljul’s account of his predecessors and contemporaries in Andalus. He speaks of considerable contact between the Eastern Caliphate and Andalus, and students travelling in search of knowledge and training [79]. Building upon his study of Dioscorides’ Herbal, he produced a supplement, named a maqalah “on those drugs which Dioscorides did not mention”, containing around sixty items [80]. This work follows the scheme and style of earlier writers, generally giving the appearance, action, and nature of each plant, its place in the accepted scheme of medicine, with its mixture or temperament (mizadj), its “powers” and its effect on any particular humour or organ [81]. Ibn Juljul gives the origin – as far as he knows it – of all but seventeen of these items: twenty-eight from India (or at any rate, coming through the Indian trade route), two from Yemen, two from Egypt (one of these also from Al-Qayrawan), one from Ceylan, one from Khwarizm. A few are from Andalus: one in general, two from near Cordova, one from near Cadiz; the Khaizuran (bamboo) has two types, an Andalusi and an Indian [82]. With the items from Andalus, he sometimes adds the name of the person who first used them or told him about them. Concerning the Bezoar stone “which counteracts all poisons . . . a yellowish stone with white streaks, Abu ‘Abd-Allah al-Siqilli told me that he saw it once in the mountains of Qurtubah.” Of Shajarat al-kaff, the Vitex agnus castus, “Tariq the herbalist, among us in Qurtubah, knows it; he is the first to have made it widely known [83].” He had other informants too: on Ribas, the rhubarb, he describes it and then says: “I enquired about the Ribas from some people from the Far East, who told me that it is a sour-tasting vegetable with fleshy leaves like those of the humad (succulents); and one reliable merchant, who knows about its use, told me that the Ribas has extremely sour roots which are found in snow-covered mountains.” His list contains the practical, the exotic and the mythical, but all were considered elements of medicine that should be known about, and mostly used [84].

|

|

Figure 9: Leaf from an Arabic translation of the Materia Medica of Dioscorides on the preparation of medicine from honey. The manuscript was copied in Baghdad in 1224 CE. (Source). |

Later authors who used Ibn Juljul’s work include Al-Ghafiqi the botanist and Ibn Maymun (Maimonides), who does not quote from him directly but mentions him as one from whom he learnt, and Ibn al-Baytar quotes him on fourteen of the drugs which occur in his supplement [85]. Ibn Juljul’s work evidently stood the test of time and was of particular use and value to scholars and practitioners in his own region of Andalus, and in the Maghrib. He used and respected the “Ancients” but did not simply transmit the Greek learning; he made valuable contributions to the practical knowledge and use of medicinal plants, and was held in great respect by contemporary and later scholars and physicians [86].

4.2. Ibn Samjun

Ibn Abi Usaybi’a tells us that Ibn Samjun who appears to have been exclusively a herbalist [87], was an expert in the art of medicine. He lived and worked in Cordoba, where he died around 1002 CE. He is known for one book, the Collection of Sayings of the Ancients and Moderns, of the Physicians and Philosophers, on the Simple Drugs. Parts of this work exist in manuscript in Oxford and London [88]. In the surviving sections of the Collection, Ibn Samjun quotes Ibn Juljul on around thirty of the items which appear in the supplement [89]. Ibn Samjun seems generally to have been neglected, yet, in the opinion of Levey, who wrote one of the best, if not the best, work on Islamic pharmacology. Ibn Samjun must be recognized as one of the greatest botanists and pharmacologists of the entire Islamic period, probably far outstripping Ibn al-Baytar and al-Ghafiqi [90]. Ibn Samjun’s account of mandrake illustrates his meticulousness. He begins with a description of its appearance and the value of its morphological structures, and then goes on to the various words used in connection with the mandrake, the degrees of its qualities, i.e. cold, warmth, moistness, and dryness, its pharmacological properties as a simple and in compound remedies for various ailments, and finally its use in a prescription as an antidote. This elaborate method of description of simples in alphabetical order became the archetype for Ibn al-Baytar centuries later when he wrote the most comprehensive work in this form on the subject [91].

4.3. Ibn Al-Wafid

Ibn Al-Wafid (997-1075) of Toledo, according to Cadi (judge) Sâ’id Al-Andalusi, is the most able of scientists in the composition of simple remedies, superior in ability to all his contemporaries [92]. What characterised Ibn Al-Wafid was his immense knowledge of medical matters and therapeutics, with the skills to treat grave and insidious diseases and afflictions [93]. Cadi Sâ’id holds that Ibn Al-Wafid spent twenty years to gather, organise, and check all the names of drugs, their properties, and their potency [94]. He preferred to use dietetic measures, and if drugs were needed, he preferred to use the simplest ones, before recommending compound drugs, and when he did use compound drugs, he gave priority to those less complex [95]. If and when he resorted to the use of compound drugs, he did so only sparingly, preferring the lowest amount possible [96]. His main work on simple drugs, Kitab al-adwiya al-mufrada, is partly extant in a Latin translation (Liber de medicamentis simplicibus) [97]. This work was not printed in Arabic, but there exists a Latin translation by Gerard of Cremona, which was later issued as a supplement to the Opp. Mesues, and also published together with the tacuin sanitasis and Al-Kindî in Strasbourg in 1531 [98].

|

|

Figure 10: Medicinal Plants in an Arabic manuscript from Iraq, late 14th century. (Source). |

Ibn al-Wafid’s work was five hundred pages long, and the Latin translation of it is only a fragment of the original [99]. There are also translations in Catalan and also Hebrew [100]. The De medicamentis simplicibus has been printed frequently, together with the Latin translation of the works of Masawaih al-Mardini (Venice 1549) or of Ibn Jazla’s Taqwim (Dispositio corporum de constitutione hominis) (Strasbourg 1532) . Ibn Al-Wafid is also the author of a pharmacopeia and manual of therapeutics entitled al-wisada fi’l-tib (book of the pillow on medicine), which according to Vernet could be a misreading of the Arabic title Kitab al-Rashad fi ‘l-tibb (guide to medicine) [101]. This work can be considered complementary to the preceding one as Ibn Al-Wafid describes compound medicine and it is a practical book; the information given is based on experience [102]. Ibn Abi Usaybi’a, the Muslim medical historian, attributes to Ibn Al-Wafid a work entitled Mujarabat fi ‘l-Tibb (medical experiments) which could probably be identified with this book just cited [103]. Ibn Al-Wafid remained renowned for his marvellous and memorable cures of very serious cases of ill health, relying on very simple and basic treatments [104].

4.4. Al-Ghafiqi

Al-Ghafiqi (d. 1165), from Ghafiq, near Cordova, is an important and well known physician and medical author. In his work, Kitab al-jami’ fi ‘l-adwiya al-mufrada (Book of Simples) there is a clear continuing adaptation of new plants not mentioned in either classical Greek sources or in comparable botanical guides written in the Muslim East [105]. This book was re-published by Max Meyerhof and G.P. Sobhy in Egypt in 1932 [106]. As an original thinker and sincere observer, Hamarneh notes that Al-Ghafiqi gave adequate, rational, and systematic descriptions of the physical properties of simples, their varieties, therapeutic uses, and the means to divulge and check adulteration [107]. Interestingly, he also differentiated between the professional duties of the physician and the pharmacist. His Materia medica manual was one of the finest on the topic that was produced during this entire medieval period [108].

4.5. Al-Idrisi

Another contemporary amongst this group was Al-Idrîsî, the famed geographer who also wrote on plants and their curative effects. Al-Idrîsî (1100-1166) wrote his Jami’ on Materia Medica, sorted alphabetically and arranged in three parts [109]. In examining the Jami’, one becomes impressed in two areas in which the author excelled in a particularly significant way:

1. Al-Idrîsî’s knowledge of the fauna and flora of many lands which he visited and mentioned in the text: North Africa (he was born in Ceuta on the northern coast of Morocco), Spain (he studied and lived in Cordoba), Sicily where he served in the palace of the Norman king, Roger II, Egypt, and other parts of Europe and Byzantium [110].

2. His acquaintance with many languages and technical botanical terms. He gives drug synonyms in Spanish, Arabic, Berber, Hebrew, Latin, Greek and Sanskrit. At the end of the section on drugs which are described under each letter of the alphabet, he gives an index of their entries [111]. He then adds explanatory remarks concerning them included unfamiliar names of simples, diseases, weights and measures, and technical words. The text also shows his dedication and diligence as a shrewd investigator. For example, he mentions how he continued his research for some time to identify a kind of thistle, the Onopordon acanthium (Linn) of which many varieties were known [112].

4.6. Al-Qalanisi

The Aqrabadhin of Al-Qalanisi (fl. late 12th century) is extant in several copies [113]. In the introduction to its 49 chapters, the author explained his motives for compiling his manual:

“I found most formularies filled with recipes of seldom needed compounded remedies, with prescribed ingredients hard to find and difficult to administer even after being prepared [114].’

Other important topics discussed by Qalanisi are:

1. The seasons, techniques, and procedures used in gathering vegetable drugs, whether fruits, flowers, leaves, roots, gums, or seeds, as well as animal drugs. He considered minerals the most important and effective of the simples gathered from the three natural kingdoms.

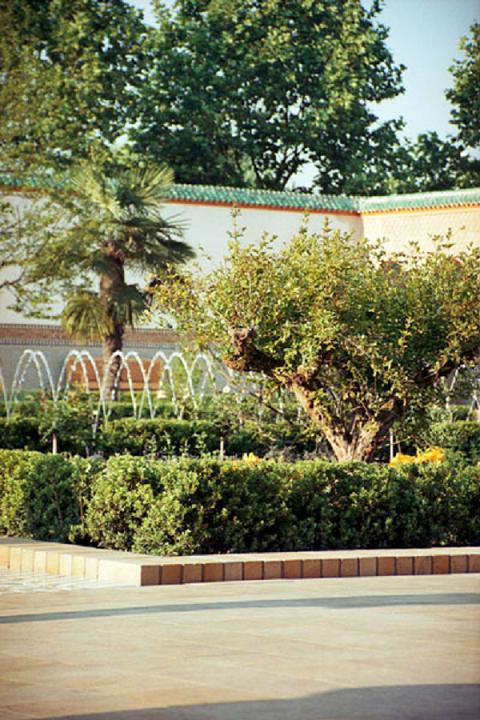

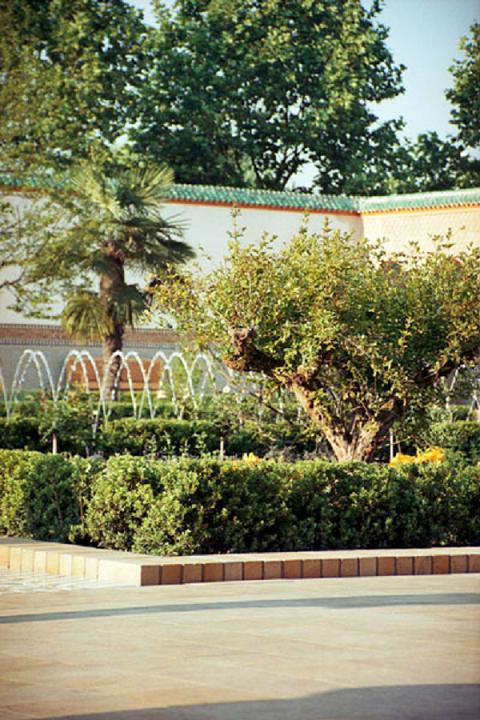

|

|

Figure 11: Views from the Islamic model for gardens: Flower-beds having regular geometric shape – rectangles, star shapes (usually eight-pointed), diamond shapes and octagons (Source); and flowerpots, which are very widely used in Islamic gardens; they are sometimes massed together in large numbers or lined against the side of pools. (Source). |

2. Interpretation of the meaning of technical words and phraseology as rendered from Greek into Arabic. For example, the transliterated words of aqrabadhin and theriac, and the meaning of such terms as sakanja bin (a mixture of vinegar and honey in water), robs, electuaries, and lohocks. The discussion is most interesting and deserves further future studies.

3. Description and administration of pharmaceutical preparations such as gargles, fumigators, eye salves and collyriums, dentifrices, liniments, suppositories and ovules, hazelnut-shaped troches, toilette products, and medicated cosmetics.

4. Description of apparatus used in the manufacturing of pharmaceuticals and their application. Qalanisi, for example, describes a clyster enema of 50 mithqals capacity (about one-half of a pint) used in medical therapy. The clyster is a tube-like cylinder divided into two parts; one is half the length of the other and is separated by a partition securely welded to the body of the cylinder. The smaller part has a mouthpiece open to the outside. The mouthpiece of the larger one is smooth and delicate for inserting the lukewarm enema liquid into the body’s cavity in such a way as to prevent admission of air. The simples used in the preparing of solutions and infusions for enemas are also specified according to need (chapter 33).

5. Mention is made of formulae used for insecticides and pesticides which include such ingredients as sulphur, ammonium salts, naphtha, tar, pitch, African rue, and laurel (chapter 48) [115].

4.7. Ibn Sirabiyun and Ibn al-Suri

At the end of this list of botanists from the Islamic West, we mention two botanists from the East.

Ibn Sirabiyun, commonly known as Serapion Junior, lived not earlier than the 11th century (c. 1070). Many works on “simples” were written under the name of Serapion. The work Selecta artis medico’ has been ascribed to the Serapions, but the material available does not justify a definite conclusion on the matter [116]. Serapion Junior, however, wrote a work based on Dioscorides and Galen entitled Liber de medicamentis simplicibus or De temperamentis simplicium, in which he mentions a similar work by Ibn Al-Wafid (Aben Guefit.) [117] Serapion Junior was perhaps translated into Latin from Hebrew, but there are no Arabic manuscripts of this work extant [118]. The work was translated into Latin by Simon de Cordo of Genoa, and also by Abraham of Tortosa [119]. Other Latin publications include the Venetian of 1479 and 1552; the latter was issued under the following title Serap. De simplic. Medicam, historia libri Vii Nicol Mutono interprete [120]. The Latin version published at Strasbourg in 1531 was based on the translation of Abraham of Tortosa and was issued together with the works of Ibn Rushd, Al-Razi and Galen [121].

Rashid al-Din Ibn al-Suri, one of the most original of Muslim botanists, was a contemporary of Ibn al-Baytar. Born at Sur (Tyre) in 1177-78, he studied medicine in Damascus under Abd al-Latif and was attached to a hospital in Jerusalem. He served under the Ayyubid Sultan al-Mu’azzam, and after the latter’s death in 1227 under his successor Al-Nasir, who appointed him chief of physicians. He finally established himself in Damascus, where he died around 1242 [122]. Al-Suri wrote a treatise on simple medicines (al-adwiya al-mufrada), wherein he discussed the views explained by one of his colleagues Taj al-Din al-Bulghari in a similar treatise [123]. What distinguished Ibn al-Suri was that he traveled extensively and explored the Lebanon range to discover and collect plants. He was accompanied by an artist whose business it was to represent them in colour as completely as possible at different stages of their growth [124]. In his work on the Materia Medica, he had the herbs which had been the subject of his investigations painted, not only as they grew, but as they appeared, when dried, on the shelves of the druggist; his is the first example of an Arabic book illustrated in colour [125].

|

|

|

Figure 12a-b: Two views of the Oriental Garden in Berlin at the Marzahn Park, opened in 2005. This 58 x 31 metre garden offers a window onto Muslim civilisation in the multicultural city of Berlin. The layout adheres to the essential traditions of the Islamic garden: the garden courtyard is centred around a fountain pavilion and divided into quarters by water channels oriented to the cardinal points; ornamentation is essential to the garden: calligraphy, floral arabesques and ‘zillij’ are found on the walls, timber carving on the pavilion, ‘muqarnas’ on the vestibule, and painted wood in the arcades; planting provides shade, colour, fragrance and taste. (Source). |

|

The apogee of botanical writing in Arabic was reached by Ibn al-Baytar (1197-1248). He was born in Malaga and studied in Seville, where he collected plants with his teachers [126]. Ibn-al-Baytar travelled in Spain and North Africa as an herbalist, and later lived in Cairo as Chief Herbalist [127]. From Egypt he travelled extensively through Syria and Asia Minor, and died in Damascus in 1248. A pupil of Ibn Rumiya, Abu al-Abbas al-Nabâti (the Botanist), Ibn al-Baytar was also greatly influenced by the work of Al-Ghafiqi’s (d. 1165) Kitab al-Adwiyat al-Mufradah (The Book of Simple Drugs). Of his outstanding works, one concerned Materia Medica, the other was on simple remedies-medical preparations containing but one ingredient [128]. The latter was a description of animal, vegetable and mineral ingredients, obtained from his own research and experiments as well as data that he had learned from Greek and Muslim sources [129]. Ibn al-Baytar collected a number of new medicinal plants which were introduced into pharmaceutical knowledge. It is held that there was not a fruit or vegetable known to horticulture at that time that was not grown in the vicinity of Malaga, his home-town [130].

Ibn al-Baytar produced his work Al-Mughni fi al-Adwiyah (the Sufficient), which is extant in many copies, notably in Paris, No. 1008, and 1029 in Arabic. The work subdivides in 20 chapters, dealing with simples for the cure of head diseases; simples for the cure of ear diseases; simples for cosmetics, simples used as counter poisons, most used simples in medicine, simples used for fevers and atmospheric alterations, and so on and so forth [131]. In this work, the author makes many observations such as the following on smallpox:

“As soon as the pustules appear on a child, he must be treated at the sole of the feet with henna, which then will prevent the disease spreading to the eyes. I have many times observed this [132].”

Ibn al-Baytar’s best known work, however, is Al-Kitab ‘l-jami’ fi ‘l-aghdiya wa-‘l-adwiyah al-mufradah (The Comprehensive book of foods and simple remedies), the most comprehensive encyclopaedic work on simple drugs. It was the greatest medieval treatise on this subject [133], a fundamental work on botany, describing 3000 simples, all listed in alphabetical order. The best manuscripts of this work are in Oxford, and there are also two in Hamburg. The translation of Galland is lost, but an Arabic manuscript is at Leyden Bibl. acad. 805 3: lbn Beitar medicamenta simplicia ord. alphab. Ex. Gal. et Dioscor [134]. However, this work has been repeatedly partly translated and edited in recent centuries. Galland made a limited translation of it into French [135]. In the 19th century Amon made a limited translation of it into Spanish, Dietz making a partial Latin translation, whilst Sontheimer made a full German version of the work [136]. A Latin version of the book was published in 1758, and its complete translation in French appeared in 1842 by Leclerc [137].

6. Medicinal Plants and their Actions

There are countless recipes from medicinal plants in a variety of works, and in a diversity of languages, which are listed in this section [138]. The following is only a sample of such recipes, kept as diverse and as short as possible, but just long enough to highlight the richness of this aspect of Islamic science. The focus is on authors who have not been reviewed in the previous sections, and those who won’t be looked at later, in order to be as diverse as possible in the approach to the rich subject of Muslim scholarship.

One of the earliest Muslim scholars is Hunayn Ibn Ishaq (809-877) who wrote a treatise on ophthalmology [139]. One of his prescriptions follows:

|

|

|

Figure 13a-b: Samples from the electronic edition of Flora of Syria, Palestine, Egyptian territory and their steppes by Dr. George Post, printed in Beirut 1884. (Source). |

|

“Recipe for a useful eye salve which soothes the pain from the very first day, with the epithet, dog’s excrement; it repels the swelling from the very first hour: Take stibium 40 drachms. acacia 40 drachms, cadmia 6 drachms, myrrh 4 drachms, aloe 2 drachms, nard and Indian lycium 4 drachms of each, castor 1 drachma, burned and washed copper 14 drachms, white lead 8 drachms, opium 2 drachms, yellow burnt vitriol 2 drachms, gum Arabic 40 drachms. Knead these remedies with the water of a decoction of roses; apply the eye salve with white of eggs and dilute it well, it will be quite excellent [140].”

6.1. Syrups

Syrup, shurba as generally known to the Arabic writers, was known as a juice concentrated to a certain viscosity so that when two fingers were dipped into it, it behaved as a semi-solid when the digits were opened. Very often sugar and/or honey were added as thickeners and sweeteners.

Ibn Kaysan [141] gives a detailed account of the preparation of syrup:

“With regard to syrup prepared with flowers such as rose, nenuphar, [water lily] violet, and similar ones, 4 ounces of flowers is taken after having removed the petals. It is immersed in very hot water, covered and left until macerated. A ratl of dissolved, concentrated, and frothy sugar is added for every 4 ounces of flowers. The pure juice of the flowers of the orange tree is added and it is cooked on a gentle fire until concentrated. It is removed and used. When the syrup to be prepared is from the juice of fruits as the apple, quince, pomegranate, and similar ones, they are crushed in a marble or black stone mortar; the juice is removed by pressure, boiled, and made to foam. It is removed from the fire and clarified. For every 4 ounces of thin liquid, a ratl of dissolved, concentrated, and frothy sugar is added. It is cooked on a light fire until it has the consistency of honey. For those fruits whose juice it is impractical to obtain except by cooking, such as the prune, cherry, jujube, and similar ones, they should be cooked in water to the point of falling apart, then ground and put through a sieve. Dissolved and frothy sugar is added and then it is cooked on a light fire to obtain the proper viscosity [142].”

“Preparation of the simple oxymel [143] syrup: Dissolve the sugar on the fire and let it froth. For each ratl of sugar, put in 2 to 4 ounces of vinegar according to its degree of acidity and the taste of the patient. Its acidity should be to a small degree [144].”

The robs, ruhb in Arabic and sapa in Latin, were syrups. Often, it was the concentrated juice of the raisin, but, most of the time, by extension, the word was applied to all fruits and plants whose juices were purified and concentrated over a fire or in the sun.

“Rob of citron. Cold, dry, effective against poisons, eases the bile, pacifies the thirst, astringent, strengthens the heart, employed in collyria for a speck in the eye or a white spot in the eye.

Preparation: Take the inside of a citron and express the juice into a stone pot. Cook on a small fire until it is reduced to a quarter.”

Further, the robs were not always used alone; when necessary, they were compounded as were simples.

“As for the robs, each one [when used] alone is stronger, but when put with sugar it becomes gentler. The robs may be put together in compounds with each other to assist in cooling [as in fevers] and in constipation. The compound is called ‘robs’. It is made from apples, quince, verjuice, pomegranate, Chinese pear, lemon, sorrel, barberry, ribes, seeds of myrtle, sumach, white mulberry that is close to being unripe, and the azerole which is called narsinjid. Tabashir is added to it and also cooked gum when it is badly needed…”

“The juices of these fruits are gathered when robs are needed, and enough crystalline sugar is thrown in to make it sweet-sour. It is cooked until it is viscous… That [juice] of quince… may be mixed with strengthening drugs for the stomach like Indian aloe wood, Chinese cinnamon, rose mastix, and so on [145].”

6.2. Lohochs

In the case of lohochs, their consistency is of a paste-like nature. The composition of lohochs is variable; often it contains mucilaginous parts of fruits and roots which are boiled and then mixed with honey and almond oil. “Lohochs are nearly always used in chest ailments [cough, laryngitis] and for the uvula. Among other things, the almond lohoch is useful to treat cough and pharyngitis. Take six dirhams each of gum arabic, gum tragacanth, starch, licorice juice, sugar, and confection, and five dirhams each of seed of decorticated quince, pip of the sugared gourd, and decorticated sweet almond. Bray them all, sieve, and add some concentrated and foaming julep. Boil until it forms a single whole. Remove and use [146].”

From Al-Samarqandi, it is learned that:

“Lohochs are moist and have a viscosity like thin sweet jelly. They are taken orally by spoon. Whatever dissolves from it is taken little by little to lengthen the period of its passage near the trachea. This is so that it may penetrate into it […] and the lungs by filtering through. It causes gentle flowing, of the moistures and adjusts them, removes hoarseness of the pharynx and the breathing, and whatever follows.”

“Some of them are cold and used to soothe hoarseness when dry coughing occurs, and for intense delicate colds so that it is mixed with them to reduce their acuteness. As for effectiveness, they provide for the prevention and take care of swollen conditions. For this, there are the cold mucilages. The mucilaginous and oily matters are such as fleawort, quince seed, marshmallow seed, violet [seed], purslane seed, [seed of] the two cucumbers, [seeds of] lettuce, poppy, mallow, pumpkin, almond, sesame, and their oils…”

“Some are warm and are used to ripen moistness, to make them milder, to cut them down, and to get rid of them. These are hyssop, iris, pine [cones], bitter almond, bitter vetch, maidenhair, thyme, pepper, long pepper, licorice root, saffron, honey, flaxseed, fenugreek, heart of the cotton seed, squill, dates, figs…” [147].

Al-Samarqandi gives a prescription with its explanation:

“Purging lohoch for phlegm. Ten parts each of flaxseed, bitter vetch, and shelled sweet almond, five parts of pine cone, seven parts of powder of crushed peeled lily root, and three parts each of gum [Arabic] and gum tragacanth are taken as a lohoch with manna or crystalline sugar.

“The main purpose of the purging lohoch is that in the purging recipe, the bitter almond may be substituted for the sweets, honey, manna or sugar, licorice rob,—its sieved part— and a little pine cone. It is gathered in gum and gum tragacanth in contrast to the cleansing lohoch [148].”

6.3. Decoctions

The word for decoction comes mainly from the Arabic for “to cook,” tabakh or “the cooked,” matbukh. Often, it is an extract from one or more sources which is concentrated to its third or fourth as a liquid.

One formulary gives a cuscuta [149] decoction:

“It is for elephantiasis, mange, dandruff, and exfoliation of the skin. It disperses phlegmatic and atrahilious [150] humors, purifies the body, clarifies the complexion, is useful for a red face, pimples, and leprosy.

|

|

Figure 14: Bronze statue of Ibn al-Baytar in his birthplace, Benalmádena on the seaward side of Castillo Bil Bil, near Malaga. Ibn al-Baytar wrote an impressive collection of simple drugs, which is regarded as the greatest Arabic book on botany of the age. He collected plants, herbs and drugs around the Mediterranean from Spain to Syria and described more than 1400 medicinal drugs, comparing them with the records of over 150 writers before him. (Source). |

“One takes ten dirhams each of Indian and Kabul myrobalan without the stones, five dirhams each of common polypody [151], Meccan senna, Cretan cuscuta, lavender, and Syrian borage, twelve dirhams each of dry, red raisins without the pips, three dirhams each of seed of endive, pulverized seed of fumitory, and stripped licorice root, a dirham of cuscuta seed, a mithqâl of roses without stems and a dirham of fennel seeds. It is all cooked in 400 dirhams of pure water until it is reduced to a quarter. It is sieved. Then there is macerated in it seven dirhams each of cassia and manna. It is filtered again and on it is thrown a dirham of sieved agaric, a quarter of a dirham of salt, and a spoonful of almond oil, and ten dirhams of sugar. It may be used [152].”

Ibn al-Tilmidh (d. 1165) of Baghdad wrote a treatise of Aqrabadhin in which he shows clear preference for experimentation over speculation and methodology. He emphasized empiricism and personal observation and the action of simple and compound drugs on the individual patient in each particular case [153]. These are the general contents of the twenty chapters of the formulary in which Ibn al-Tilmidh gives due credit to previous authors from whom he copied, given in Hamarneh’s outline, out of which the following, including herbs and plants, has been selected [154].

2. On pills or pastils containing 27 recipes and hieras (iyarijs), including cough elixirs. For examples, a recipe for the treatment of a child’s cough consists of equal parts of opium, gum Arabic, licorice, and white poppies kneaded in mucilage of fleawort. It is then made into pills to be sucked or chewed rather than swallowed, for better results. This is similar, only in a primitive way, to modern chewing tablets and lozenges now in wide use. Another prescription calls for licorice, tragacanth, sweet almonds, gum Arabic, and sugar all kneaded in mucilage of quince, which was then made into pastilles.

3. On powder containing 26 recipes including the following ingredients: clays, cumin, coriander, roses, and dodder recommended for a variety of ailments. For example, a recipe to treat against diabetes mellitus reads: five drams each of dried leaves of coriander and red rose mixed together with four drams of the sour seeds of pomegranate all to be toasted, ground, and passed through a sieve, then folded into powders for ready use.

4. On good-tasting and fragrant-smelling confections, incorporating aromatic spices such as aloes, ginger, saffron, and cardamom. Some recipes are used as antidotes against poisoning, containing terra sigillata and laurel seeds as main ingredients. Another called “joy confection” recommended for cure of heart and liver ailments, a reminder of analogous recipes used in China and Japan having a similar name [155]. The rest of the 26 recipes in this chapter were generally recommended for the stomach and the digestive system.

7. On syrups of such ingredients as apples, roses, oxymel, or sandalwood, mainly cooked with sugar to the appropriate consistency, 27 recipes.

8. On robs, thickened, good-tasting juices of fruits, preferably cooked with sugar to a much thicker consistency than that of the syrups, 10 recipes.

15. On oral hygiene including dentifrices for teeth and gum care, in 15 recipes incorporating such ingredients as sweet Cyprus, alum, gailnut, pellitory, chalk, sumac, and borax.

18. Remedies used to stop nose and wounds bleeding in 5 recipes including such ingredients as alum, vitriol, frankincense, and dried and ground herbs.

20. Remedies for increasing sweating and perspiration, as borates, or to decrease the same, such as dried coriander and sumac. No adequate explanation for administering these remedies is given, except the fact that doctors were called upon for advice and treatment in such cases [156].

An instance from Ibn al-Baytar on the medical use of hazelnut brings together the view of diverse authorities (not cited in preceding sections), and it reads: “357. Bunduq [Corylus avellana li., hazelnut].

lbn Masawaih (al-Maradini): The hazelnut is more compact and less moist than the nut; it is more nourishing if it is digested, because of its density. It is less oily than the nut and richer nutritionally. It is slightly acidic. It remains in the stomach for a long time. It creates bile. It gathers in the jejunum, fortifies it, and helps it when it is affected. It has a special power in that when it is eaten ahead of time it is good against poisons; it is also good for this purpose afterward when taken with rue and figs. It intoxicates.

Al-Masihi (Ali Abbas): It breaks down the viscous humours. It is good for expectoration which comes from the chest and from the lung.

Al-Tabari: Taken with a fig and some rue, it is useful against the bite of the scorpion. In my youth, living around Mosul, I saw people of the country bring the hazelnuts in their arms and affirm that they found them effective for scorpion bites.

Ibn Sina: It touches off a little beat and dryness. It provokes vomiting.

Al-Isra’ili: it provokes more flatulence and borborygmi than the nut. It inflates one more with wind, especially if it is ingested with its internal covering. Yet, this covering is strongly astringent and holds the wind; if it is removed, the hazelnut passes more easily and is digested better.

Al-Razi on his “Treatise on the Correctives of Foods” claims: It passes slowly and nourishes much. One corrects it especially with sugar. If one has made bad use of it to the point of distending the stomach, then it is necessary for one with a cold temperament to drink after it some honeyed water, and with hot temperament, a julep. If this is insufficient, it is necessary to take a prepared laxative. It is essential that one eat it without its covering [157].’

While herbs were clearly studied for their medicinal benefits, they were also described in medical works and general literature as being advantageous or disadvantageous to one’s regimen [158]. Numerous beliefs about the nature of each food and its suitability to individual temperaments were deduced, and many dishes, Dols notes, were eaten for their promotion of health as much as for their taste and nutritional properties [159]. Furthermore, herbs were used in the prevention of disease, for example as fumigants during periods of epidemics [160].

There are some good secondary sources in the field of botany for any curious reader wishing to explore the matter further (but like many essential areas of Muslim science: mainly available in Germany and only in German) [161].

With regard to the relationship of Muslim botany with the modern, names of plants reached the West through the intermediary of Muslim works [162]. Levey also rightly points out that because of its accumulation of thousands of years of experience, Muslim pharmacology may still contain something of value for modern science. The medicinal properties, particularly of botanicals known to Muslim physicians and apothecaries, deserve great attention. Some important medicinal plants prescribed today have been explored with success, and more remains to be done. He believes that clues to valuable drugs can be found in the early Arabic texts [163].

The best conclusion on the subject, though, is in the words of the great botanist, Ibn Juljul. He says:

`I had great desire to know precisely material medica which is the basic study of composed drugs, and I have furthered the study of this subject with much care. God, most kind, has given me the means to accomplish my wish, which was to bring to life what I feared whose knowledge could be lost, a loss of something that is of great advantage for the health of humans. It is, indeed, God Who has created the cure, and has spread it amongst plants thriving on the soil, and amongst the animal kingdom, that move on the land, or swim in the waters, and in minerals under the ground, for all this is witness of the power for healing, a gift and a bounty from God the Almighty [164].’

Footnotes

[1] M. W. Dols: “Herbs, Middle Eastern”, Dictionary of Middle Ages; Joseph R. Strayer (editor in Chief), New York: Charles Scribner’s Son, 1980-, vol. 6, pp. 184-7; p. 184.

[2] A.Whipple: The Role of the Nestorians and Muslims in the History of Medicine. Microfilm-xerography by University Microfilms International Ann Arbor, Michigan, 1977, p. 33.

[3] Will Durant, The Age of Faith. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1950, p. 245.

[4] S.P. Scott: History of the Moorish Empire in Europe; 3 vols., J.B. Lippincott Company, 1904; vol. 3, p. 435.

[5] M. W. Dols, “Herbs, Middle Eastern”, op. cit., p. 184.

[6] R. Kruk: “Nabat”, Encyclopaedia of Islam, vol. 7, pp. 831-4.

[7] Ibidem.

[8] Idem, 831.

[9] M. W. Dols: “Herbs”, op. cit., p. 185.

[10] Seyyed Hossein Nasr: Science and Civilisation in Islam, Islamic Texts Society, 1987, 2nd edition 2003, p. 112.

[11] M. W. Dols: “Herbs”, op. cit., p. 185.

[12] S. H. Nasr: Science and Civilisation, op. cit., p. 112.

[13] Juan Vernet and Julio Samso: “Development of Arabic Science in Andalusia”, in Encyclopaedia of Arabic Science, edited by R. Rashed, London: Routledge, vol. 1, pp 243-76; p. 262.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ikhwan al-Safa: Rasail; Bombay 1305 H; vol. 2, p. 107.

[16] Ibid, p. 108.

[17] Ibidem.

[18] P. Johnstone: “Ibn Juljul, Physician and Herbalist”, Islamic Culture, vol. 73, 1999, pp. 37-43; p. 41.

[19] Ibidem.

[20] Ibidem.

[21] Al-Ghazali: Al-Hikma fi ‘l-makhlukat, Cairo 1934.

[22] R. Kruk: “Nabat”, Encyclopaedia of Islam, op. cit., p. 833.

[23] Al-Risala al-Kamiliyya/Theologus Autodidacticus, ed. and tr. M. Meyerhof and J. Schacht, Oxford 1968, p. 42.

[24] R. Kruk: Nabat op. cit., p. 833.

[25] See H. Peres: La poésie andalouse en arabe classique au XIe siecle, Paris 1953, pp. 161-201; G. Schoeler: Arabische Naturdichtung. Die zahriyat, rabiiyat und rawdiyat von ihren Anfaengen bis Assanawbari, Beirut 1974.

[26] Philip K. Hitti, History of the Arabs (1937), New York: Palgrave Macmillan, new edition of the 10th revised edition, 2002, pp. 574 ff.

[27] A. Whipple: The Role, op. cit., p. 33.

[28] Ibidem.

[29] Ibn Battuta: Voyages d’Ibn Battuta, Arabic text accompanied by French translation by C. Defremery and B.R. Sanguinetti, preface and notes by Vincent Monteil, I-IV, Paris, 1968, reprint of the 1854 edition; Ibn Battuta: Travels in Asia and Africa; tr and selected by H.A.R. Gibb; George Routledge and Sons Ltd; London, 1929.

[30] M. W. Dols: “Herbs”, op. cit., p. 185.

[31] G. Sarton: Introduction to the History of Science (3 v. in 5), Carnegie Institution of Washington Publication no. 376. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkens, 1927; vol. 2; p. 303.

[32] M. W. Dols: “Herbs”, op. cit., p. 185.

[33] M.A. H. Ducros: Essai sur la Droguerie Populaire Arabe; Cairo 1930, p. iii.

[34] Ibid.

[35] Ibid.

[36] C. Elgood: A Medical history of Persia, Cambridge University Press, 1951. pp 272 ff

[37] Ibid.

[38] Ibid.

[39] Ibid.

[40] Ibid.

[41] G.Wiet et al.: History of Mankind; vol. 3: The Great medieval Civilisations; Translated from the French, George Allen & Unwin/UNESCO, 1975, p. 655.

[42] Ibid.

[43] P. Johnstone: “Ibn Juljul, Physician and Herbalist”, op. cit., p. 37.

[44] S.P. Scott: “History”, op. cit., p. 515.

[45] P. Johnstone: Ibn Juljul, op. cit., p. 37.

[46] Ibid.

[47] G. Wiet et al.: History; op. cit., p. 655.

[48] J. Scarborough: “Herbals”, in Dictionary of Middle Ages, Joseph R. Strayer (editor in Chief), New York: Charles Scribner’s Son, 1980-, vol. 6, p. 179.

[49] Ibid.

[50] Ibid.

[51] Ibn Wahshiya (903-4): Al-Filaha al-nabatiyya‘‘. Agr. Ms. 490, Dar al-Kutub, Cairo.

[52] T. Fahd: “Botany and agriculture” in Encyclopedia of the History of Arabic Science. Edited by R Rashed; Routledge, London and New York: 1996. vol. 3, pp. 813-52.

[53] L’Agriculture Nabatéene. Translation into Arabic attributed to Abu Bakr Ahmad b. Ali al-Kasdani, known as Ibn Wahshiya (4th-10th century). Critical edition by T. Fahd, 2 Vols, Damascus, 1993, 1995.

[54] M. Levey: Early Arabic Pharmacology, Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1973, p. 109.

[55] The text used here is the printed edition of Bulaq, 1294 H, pp. 84-152 for the simples. It was printed in Latin Venice and Lyons in 1523 under the title of Liber regius.

[56] M. Levey: Early Arabic, op. cit., p. 109.

[57] G.Wiet et al.: History, op. cit., p. 655.

[58] P. Johnstone: “Ibn Juljul”, op. cit., p. 39.

[59] I. R. and L.L. al-Faruqi: The Cultural Atlas of Islam, Prentice Hall College Div., 1986, p. 327.

[60] S.P. Scott: “History”, op. cit., p. 515.

[61] M. W. Dols: “Herbs”, op. cit. p. 185.

[62] M. Ulmann: Die Natur- und Geheimwissenschaften im Islam, Leiden 1972; p. 66.

[63] B.Silberberg: Das Pflanzenbuch des Abu Hanifa Ahmed ibn Da’ud al-Dinawari. Ein Beitrag zur Geschichte der Botanik bei den Arabern, dissertation, Breslau, published in part in Zeitschrift fur Assyriologie 24 (1910): 225-65; 25 (1911): 38-88.

[64] Ibid.

[65] B. Lewin: The Book of Plants of Abu Hanifa al-Dinawari, Part of the alphabetical section (alif-zay). Edited from the unique MS. in the Library of the University of Istanbul, with an introduction, notes, indices, and a vocabulary of selected words, Uppsala-Wiesbaden 1953; B. Lewin: The Book of Plants. Part of the monograph section, Wiesbaden 1974.

[66] Al-Dinawari, Abu Hanifa: Le Dictionnaire botanique d’Abu hanifa al-Dinawari…., compiled according to the citations of later works, edited by M. Hamidullah, Cairo, coll. Institut Francais d’Archeologie Orientale, textes et traductions d’auteurs orientaux, V; 1973.

[67] R. Kruk: “Nabat”, op. cit., p. 832.

[68] Ibid.

[69] Ibid.

[70] B. Lewin: “The Third part of Kitab al-Nabat of Abu Hanifa al-Dinawari”, Orientalia Suecena 9, 1960, pp: 131-6.

[71] T. Bauer: Das Pflanzenbuch des AbuHanifa al-Dinawari, Wiesbaden 1988.

[72] R. Kruk: “Nabat”, op. cit., p. 832.

[73] T. Fahd: “Botany and agriculture”, op. cit.

[74] Ibid; Charles Pellat, “Dīnavarī, Abū Hanīfa Ahmad“, Encyclopedia Iranica.

[75] P. Johnstone: “Ibn Juljul”, op. cit., p. 37.

[76] Ibid.

[77] Cf. S.K. Hamarneh and G. Sonnedecker: A Pharmaceutical View of Abulcasis al-Zahrawi in Moorish Spain (Leiden 1963).

[78] Ibn Abi Usaibi’ah: ‘Uyun al-Anba’ fi Tabaqat al-Atibba’ (Cairo 1882), and al-Qifti: Tarikh al-Hukama, ed. J. Lippert (Leipzig 1903).

[79] Ibn Juljul: Tabaqat al-Atibba’ wa ‘I-Hukama’, ed. F. Sayyid, (Cairo 1955).

[80] P. Johnstone: “Ibn Juljul”, op. cit., p. 39.

[81] Bodleian Ms. Hyde 34. See A New Catalogue of Islamic Arabic Manuscripts in the Bodleian Library, Oxford. Vol. I: Arabic Manuscripts on Medicine and Related Topics, by Emilie Savage-Smith. The Supplement was edited and translated into German by A. Dietrich, Gottingen 1993; and (English) by P.C. Johnstone, unpubl. D. Phil. diss., Oxford, 1972.

[82] P. Johnstone: “Ibn Juljul”, op. cit. p. 40.

[83] Ibid.

[84] Ibid.

[85] The abridged version of The Book of Simple Drugs of Ahmad ibn Muhammad al-Ghafiqi by Gregorius Abu’l-Farag (Barhebraeus), ed. M. Meyerhof and G.P. Sobhy (Cairo 1932- 40): Maimonides, Sharh Asma’ al-Uqqar, ed. M. Meyerhof (Cairo, 194); Ibn al-Baitar: al-Jami’ li-Mufradat al-Adwiyah wa ‘1- Aghdhiyah (Cairo 1874).

[86] P. Johnstone: Ibn Juljul; op. cit., p. 42.

[87] Ibid, p. 41.

[88] Ibn Samjun’s work: Bodleian Ms. Bruce 47, 48; British Library, Or. 11614; see P. Kahle, “Ibn Samagun und sein Drogenbuch,’ in Documenta Islamic Ibedita, (Berlin 1952), 25 ff.

[89] P. Johnstone: “Ibn Juljul”, op. cit., p. 41.

[90] M. Levey: “Early Arabic”, op. cit., p. 110.

[91] M. Levey: Early Arabic; op. cit., p. 108.

[92] Ibn Abi Usaibia: Uyun al-Anba; French partial translation (ed by Jahier-Noureddine); op. cit., p.42.

[93] L. Leclerc: Histoire de la médecine Arabe; 2 vols. (Paris 1876), p. 545.

[94] Ibn Abi Usaybia: Uyun al-Anba; Fr partial tr (ed by Jahier-Noureddine); op. cit., p.42.

[95] E. H. F. Meyer: Geschichte der Botanik; I-IV, Konigsberg, 1854-7; vol. 3, pp. 205-8.

[96] Ibn Abi Usaybia: Uyun al-Anba; Fr partial tr (ed by Jahier-Noureddine); op. cit., p.42.

[97] F. Wustenfeld: Geschichte der arabischen Aerzte (Gottingen 1840), p. 82.

[98] D. Campbell: Arabian Medicine, op. cit., p. 101.

[99] L. Leclerc: Histoire, op. cit., p. 546.

[100] Emilia Calvo: Ibn Wafid: in the Encyclopaedia of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine in Non Western Cultures; H. Selin Editor; Kluwer Academic Publishers. Dordrecht/Boston/London, 1997. p.438.

[101] Ibid.

[102] Ibid.

[103] Ibid.

[104] Ibn Abi Usaybi’a: Uyun al-Anba’; Fr partial tr (ed by Jahier-Noureddine), op. cit., p.42.

[105] J. Scarborough: Herbals; op. cit., p.179.

[106] The abridged version of The Book of Simple Drugs of Ahmad ibn Muhammad al-Ghafiqi by Gregorius Abu’l-Farag (Barhebraeus), ed. M. Meyerhof and G.P. Sobhy (Cairo 1932), p. 40.

[107] S.M. Hamarneh: Origins of Pharmacy and Therapy in the Near East. Tokyo: The Naito Foundation, 1973, p. 92.

[108] Ibid.

[109] Ibid.

[110] Ibid , p. 93.

[111] Ibid.

[112] For this study of Jami’ Sifat Ashtat al-Nabat wa-Dhurub Asnáf al-Mufradat min al-Ashjàr wâ’l-Thimãr wa’l-Azhar wa-‘l-Hayawanat by Abu ‘Abd Allah Muh. al-Sharif al-Idrîsî; Istanbul copy no. 1343, completed in 1291, in 185 fols., by the copyist ‘Abd al-‘Aziz b. Mah. al-Ya’qûbi.

[113] For biographical information on Badr al-Din Muh. b. Bahrâm al-Qalanisi and his Aqrbadhin (completed in Samarqand about 1194), see l. A. Usaybi’a, ‘Uyun al-Anba’, vol. 2: 31; Brockelmann, Geschichte der Aarabisch Literatur (Leiden: Brill, 1937 ff.), vol. 1: 644 and Supplement, vol. 1: 893; and Iskandar, Catalogue, Wellcome, London, pp. 79-80.

[114] S.K. Hamarneh: Origins of Pharmacy; op. cit., pp. 64-5; For this study, Hamarneh says that he consulted the following copies of Qalanisi’s Aqrabadhin: The Panta-Bihar, India manuscript copied by al-Anwari in 1380, in elegant Nasta’liq script (149 fols., 19 lines, and 9 x 18 cm. in size); The British Museum copy, Or. 2805, fols. 1-110; and the Zahiriyah/Damascus, MS T49, written in 1432 in Naskh script in 82 fols., described in detail in the Zahiriyah Catalogue, Index, Damascus 1969, pp. 308-310.

[115] S.K. Hamarneh: Origins of Pharmacy, op. cit., pp. 64-5.

[116] D. Campbell: Arabian Medicine, and its Influence on the Middle Ages. Amsterdam: Philo Press, 1926; reprinted 1974; p. 100.

[117] Ibid.

[118] Ibid.

[119] A translation which was published by Anthony of Parrna under the title Liber Serapionis aggreqatus in medicinis simplicibus, translat. Simonis Januensis. interprete, Abraham Judeo Tortuosiensi de arabico in Latinum (Mediolani, 1473).

[120] D. Campbell: Arabian medicine op. cit., p. 100.

[121] On Ibn Sirabiyun, see Peter E Pormann, Ibn Serapion: A physician at the Crossroads between East and West, al-Mashriq 82.2 (2008), 343-59.

[122] G Sarton: Introduction, op. cit., vol. II, p. 649.

[123] Ibid.

[124] Ibid.

[125] S.P. Scott: History, op. cit., p. 515.

[126] M. W. Dols: “Herbs”, op. cit., p. 185.

[127] A. Whipple: The Role, op. cit., p. 34.

[128] Ibid.

[129] Ibid.

[130] S.P. Scott: History, Polypody Any plant of the genus Polypodium, A genus of plants of the order Filices or ferns. The fructifications are in uncovered roundish points, called sori, scattered over the inferior surface of the frond or leaf. There are numerous species. vol. 2, op. cit., p. 620.

[131] L. Leclerc: Histoire, op. cit., p. 235-6.

[132] L. Leclerc: Histoire, p. 236.

[133] A. Whipple: The Role, op. cit., p.34.

[134] D. Campbell: Arabian Medicine, op. cit., p. 101.

[135] L. Leclerc: Histoire, op. cit., p. 233.

[136] Ibid, pp. 233-4.

[137] Ibn al-Baytar (1874), Al-jami’…, vols. I-IV (Cairo 1291); French translation by Lucien Leclerc, I-III, Paris, 1977-83.

[138] Such as: M. Levey: Early Arabic, op. cit.; S.K. Hamarneh: Origins of Pharmacy, op. cit.

[139] The Book of the Ten Treatises on the Eye Ascribed to Hunain Ibn Ishaq (809-877).

[140] The Book of the Ten Treatises on the Eye Ascribed to Hunain Ibn Is-Haq (809-877 A. D.), edited by Max Meyerhoff (Cairo: Government Press, 1928), p. 133; M. Levey Early Arabic; op. cit., pp. 121-2.

[141] Saladin d’Ascoli of Salerno (15th cent.) mentioned by P. Guigues in his edition of al-Shirazi’s Kitab al-hawi (Beirut, 1903) pp. 19-20.

[142] Ibn Kaysan in M. Levey, Early Arabic, op. cit., pp. 75-6.

[143] Combination of honey and vinegar.

[144] Ibn Kaysan in M. Levey, Early Arabic, op. cit., p. 20.

[145] In M. Levey: Early Arabic, op. cit., pp. 76-7.

[146] Ibid, p. 77.

[147] Al-Samarqandi; fol 23 a, in M. Levey, op. cit., p. 77-8.

[148] Al-Samarqandi; fol 24b, in M. Levey, op. cit., p. 78.

[149] Cuscutan: genus of twining leafless parasitic herbs lacking chlorophyll: dodder; syn: genus Cuscuta.

[150] Irritable as if suffering from indigestion; syn: bilious, dyspeptic, liverish.

[151] Polypody Any plant of the genus Polypodium, A genus of plants of the order Filices or ferns. The fructifications are in uncovered roundish points, called sori, scattered over the inferior surface of the frond or leaf. There are numerous species.

[152] In M. Levey: Arabic, op. cit., pp. 78-9.

[153] Cairo manuscript Tibb no. 141 (3) in 41 fols. dated 913 A.H. and others (The British Museum and Wellcome in London; the National Library of Medicine and the Rabat copies). At the National Library of Cairo, Hamarneh identified the manuscript 1212 Tibb as Ibn al-Tilmidh’s Aqrdbadhln, in 69 fols. written in Naskh script, 17 lines each page.

[154] S.M. Hamarneh: Origins of Pharmacy, op. cit., pp 60-4.

[155] A drug jar inscribed as a “joy” confection is represented in the Naito Museum of Pharmaceutical Science and Industry. See Hamarneh, Temples of the Muses and a History of Pharmacy Museums, Tokyo, The Naito Foundation, 1972, pp. 105-6, and 109.

[156] S.K. Hamarneh: Origins of Pharmacy, op. cit., pp 60-4.

[157] In M. Levey: Early Arabic, op. cit., pp. 114-5.

[158] M. W. Dols: “Herbs”, op. cit., p. 186.

[159] Ibid.

[160] Ibid.

[161] Works such as: Max Meyerhof: “Uber die Pharmacologie und Botanik des Ahmad al-Ghafiqi”, Archiv fur Geschichte der Mathematik und Naturwissenschaft 13, 1930: pp. 65-74; Max Meyerhoff: “Esquisse d’histoire de la pharmacologie et de la botanique chez les Musulmans d’Espagne”, al-Andalus 3, 1935: pp. 1-41; M. Ullmann: Medizin in Islam, Leiden/Cologne, 1970; idem, Die Natur und Geheimwissenschaften im Islam, Leiden, coll. handbuch der Orientalistik, I. VI, 2, 1972; E. H. F. Meyer: Geschichte der Botanik, I-IV, Konigsberg, 1854-7.

[162] G. Wiet et al.: History, op. cit., p. 655.

[163] M. Levey: Early Arabic, op. cit., preface, pp vii-viii.

[164] Ibn Abi Usaybi’a: Uyun al-Anba fi Tabaqat al-Atiba; Partial French translation of chapter 13 on physicians of Western Islam; by H. Jahier and A. Noureddine ( Algiers 1958), p. 40.

© FSTC, 2009.

4.7 / 5. Votes 171

No votes so far! Be the first to rate this post.

Muslim Heritage:

Send us your e-mail address to be informed about our work.

This Website MuslimHeritage.com is owned by FSTC Ltd and managed by the Foundation for Science, Technology and Civilisation, UK (FSTCUK), a British charity number 1158509.

© Copyright FSTC Ltd 2002-2020. All Rights Reserved.